-

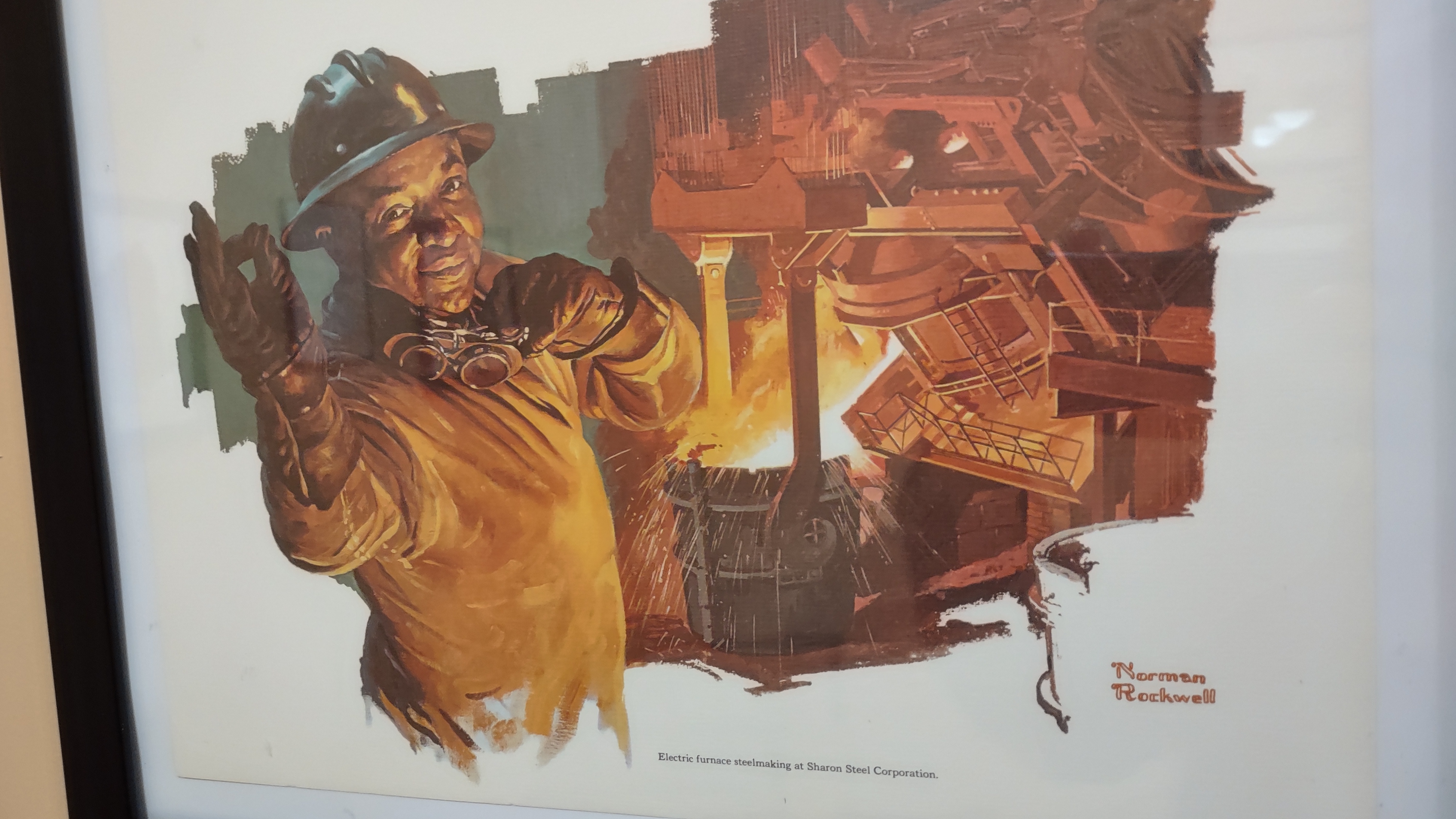

The Steelmaker

The Steelmaker, placed by Cache Owner Ed_S a decade ago, calls us to a time when steel was king.

Coordinates converge on our neighbor in the northeast.

At Ground Zero, the Youngstown Historical Center of Industry and Labor partners with YSU, training student interns who will advance to museum careers. Traveling educators use story and objects to connect past and future generations with their Youngstown past.

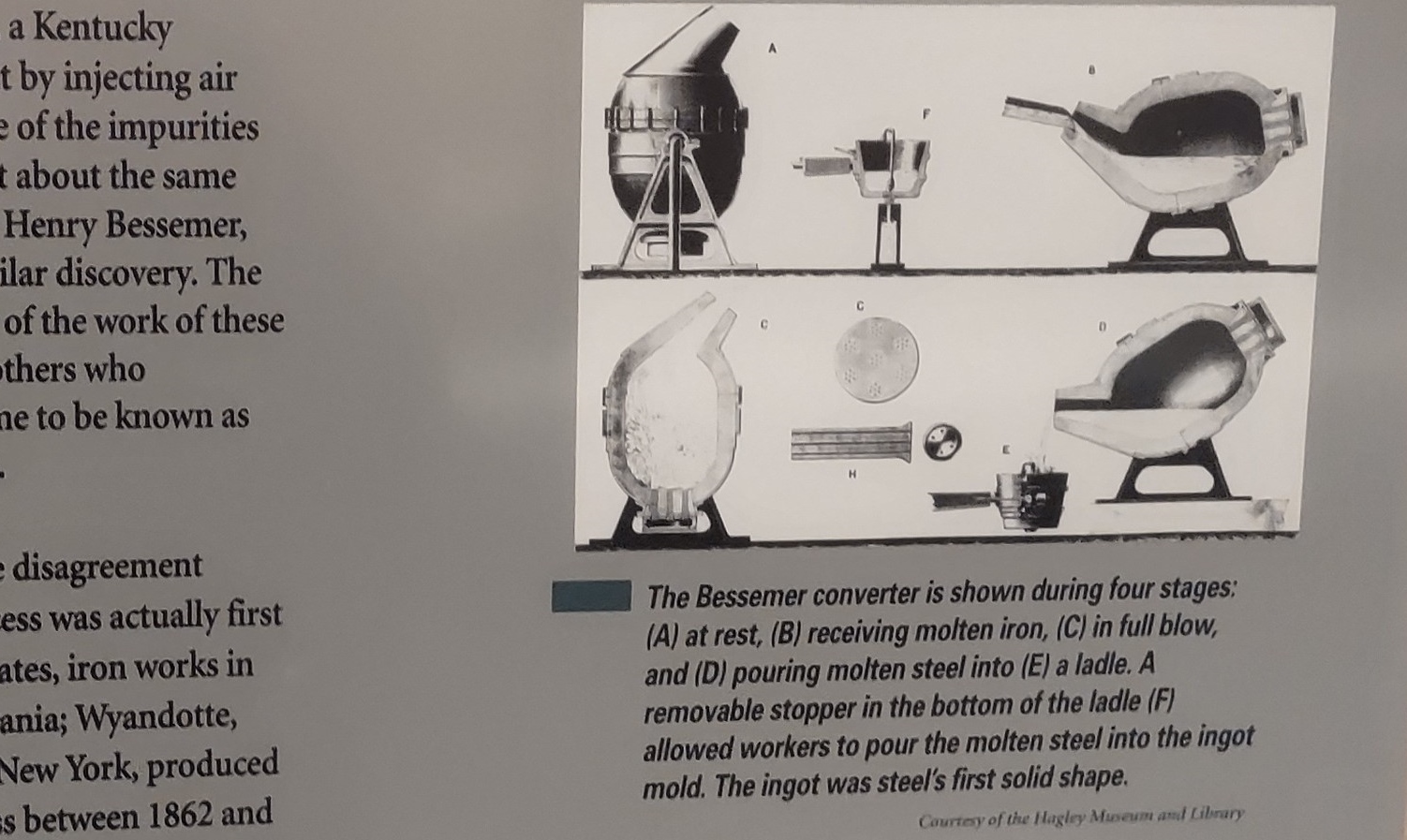

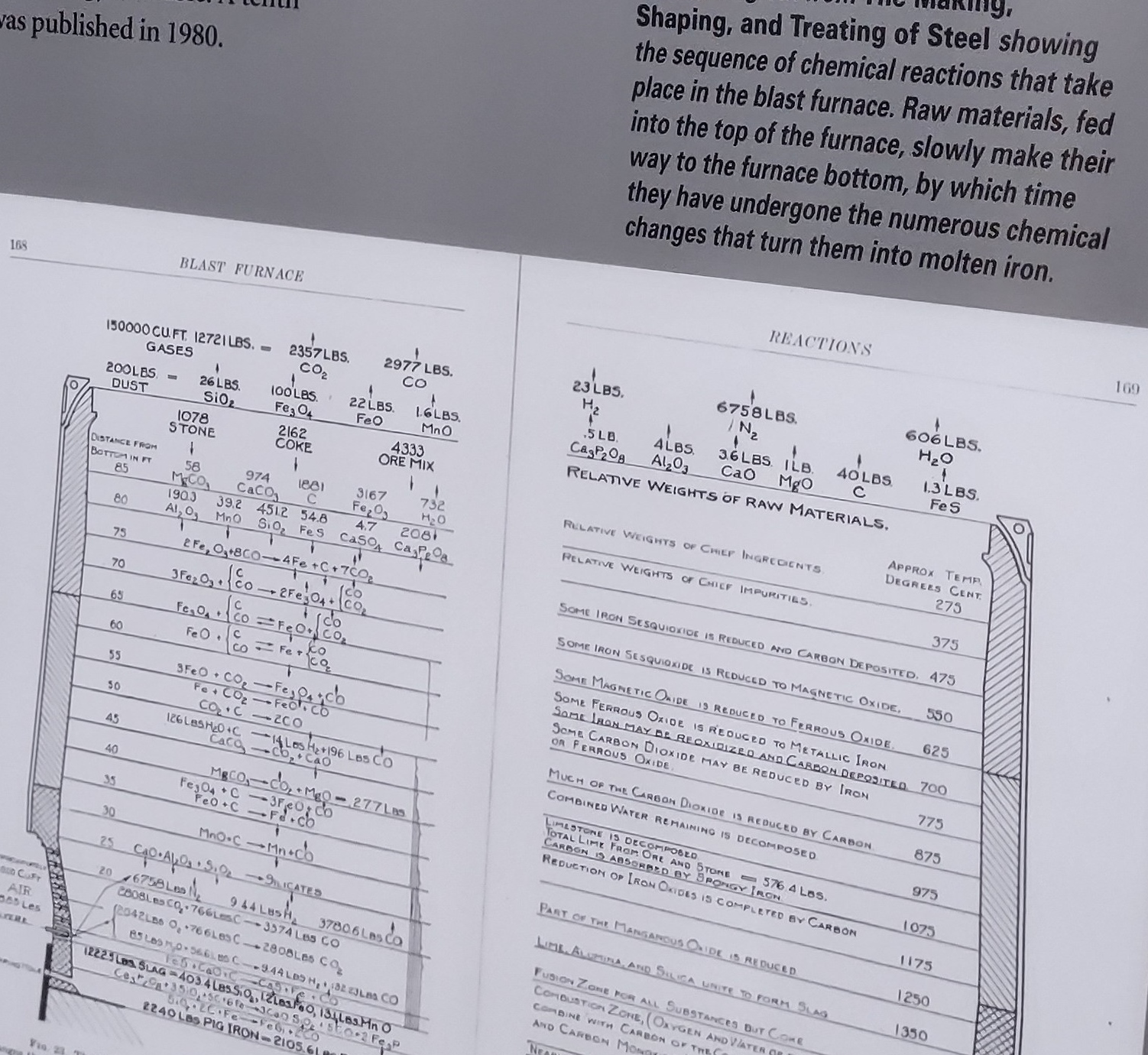

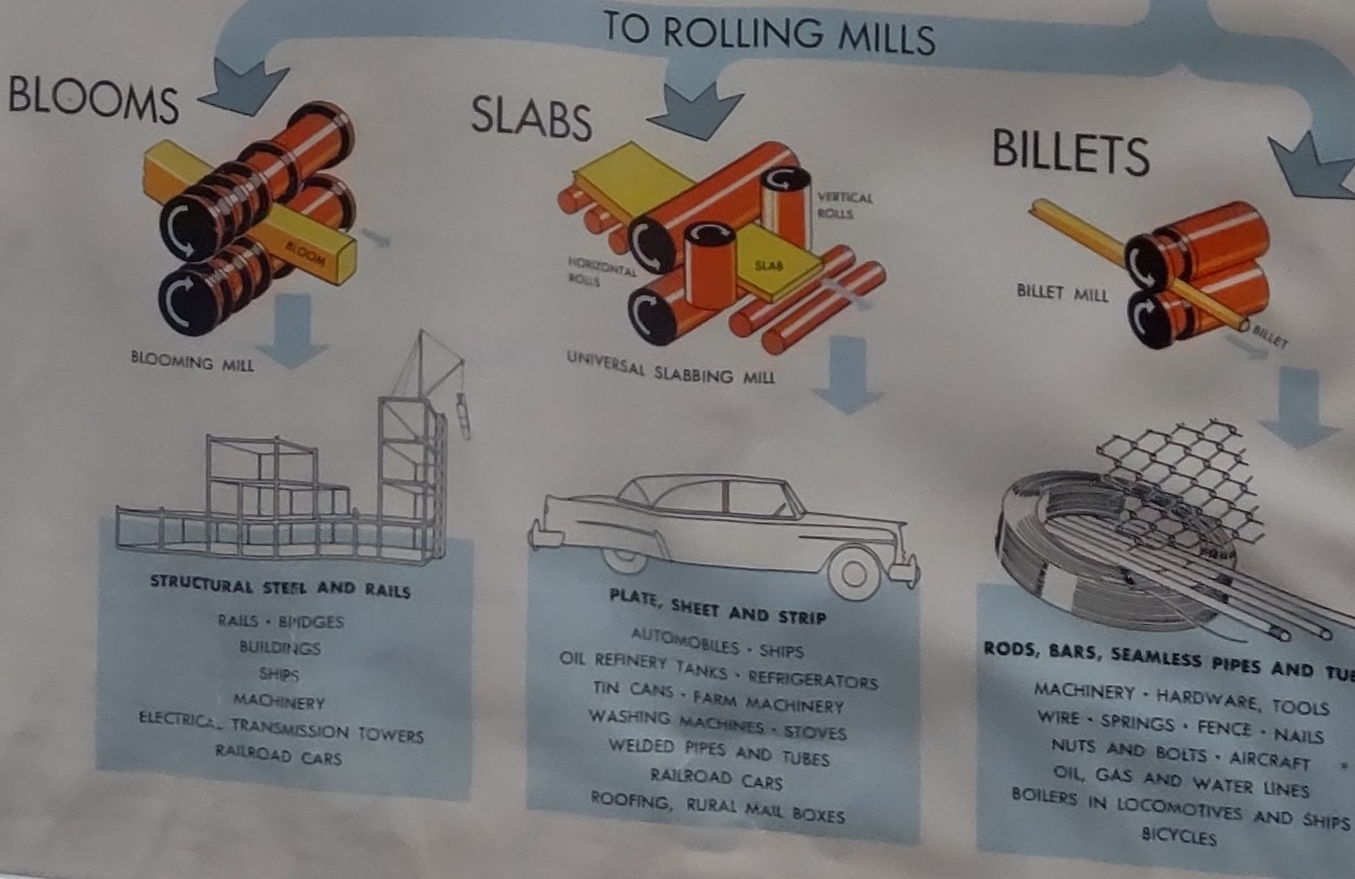

As our geotrail winds inquisitively through the doors, we encounter words like Bessemer, basic oxygen, open hearth, and electric arc, processes for burning impurities out of molten iron to make steel.

We meet the Pollacks, a three generation iron and steel family. They employed 500 workers in 1920, making 100-ton cars to transport molten iron and steel and by-products. The third generation went to Yale and felt life would go on as usual, in the large mansion built by his father. Markets changed, and the company closed in 1983. An American success story came and went.

Way back in 1620, early colonials built the first iron furnaces, and then began exporting pig iron back to the mother country. From there, the race took off to get the most iron the fastest.

Relentlessly, steam engines, train cars, and railroad tracks all demanded iron. Iron nails, axe heads, kettles, and cannonballs held life together across the colonies and states.

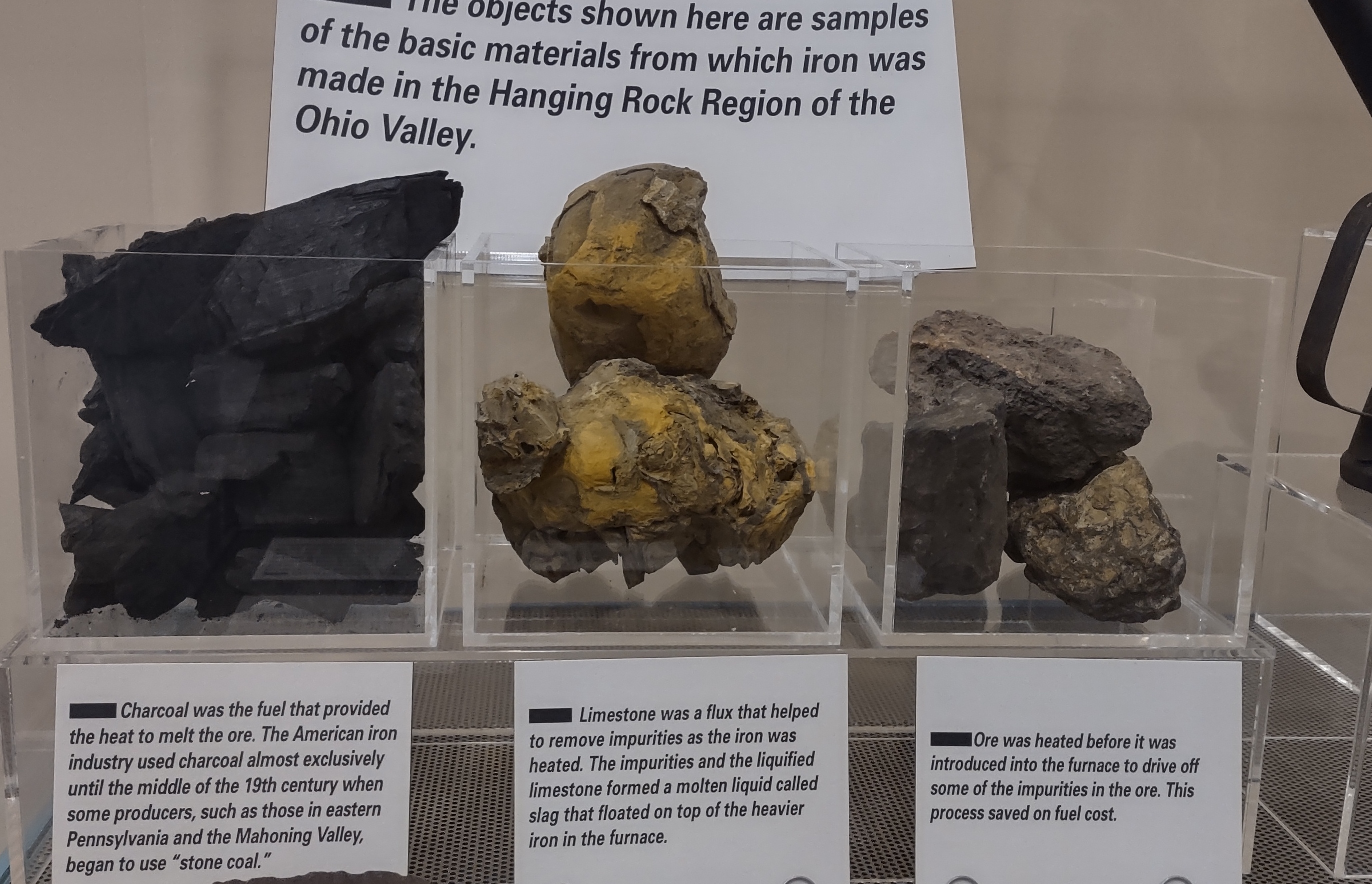

As the Age of Iron depleted New England soils, investors moved to the Ohio and Mahoning Valleys. The Triple Crown of charcoal, limestone, and iron ore was plentiful. Furnaces appeared where raw materials were located and drained them to the last drop.

A community of 500 people sprang up around the 200 men who made the charcoal and ran the furnaces. Management owned everything, paying wages in printed money that could only be used at the company store. Forty-foot circles of charcoal mounds burned 45 cords of wood at a time, consuming 400 acres of wood in a year.

As forests dwindled in the mid-1800s, coal was pulled from the ground to burn instead. By the 1870s when valley coal and iron ore was depleted, raw materials were brought in from other locations.

In 1890, the newly invented Bessamer converter made the US first in global steel production.

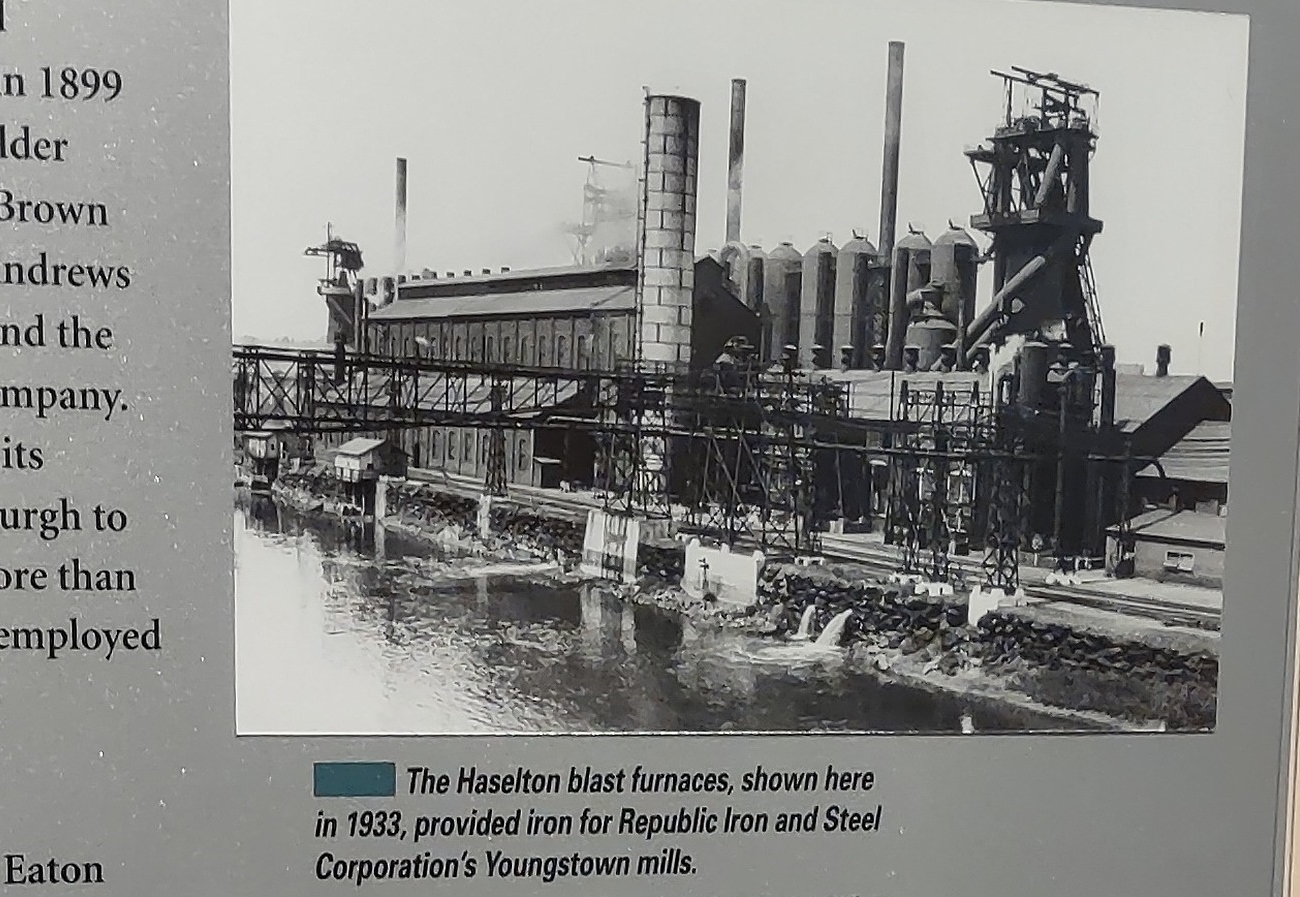

By the early 1900s, 20 miles of steel mills straddled the Mahoning Valley, ranking second only to Pittsburgh in national steel production. A river for cooling, and a railroad for transportation, attached to every mill. Spectacular growth of the industry and the great wealth it created for steel barons would eventually leave devastated forests, polluted waterways, and jobless communities in its wake.

Youngstown Sheet and Tube quickly morphed from iron to steel production as the iron market shifted to steel. Twenty years later, annual sales were $100 million, the highest in the state.

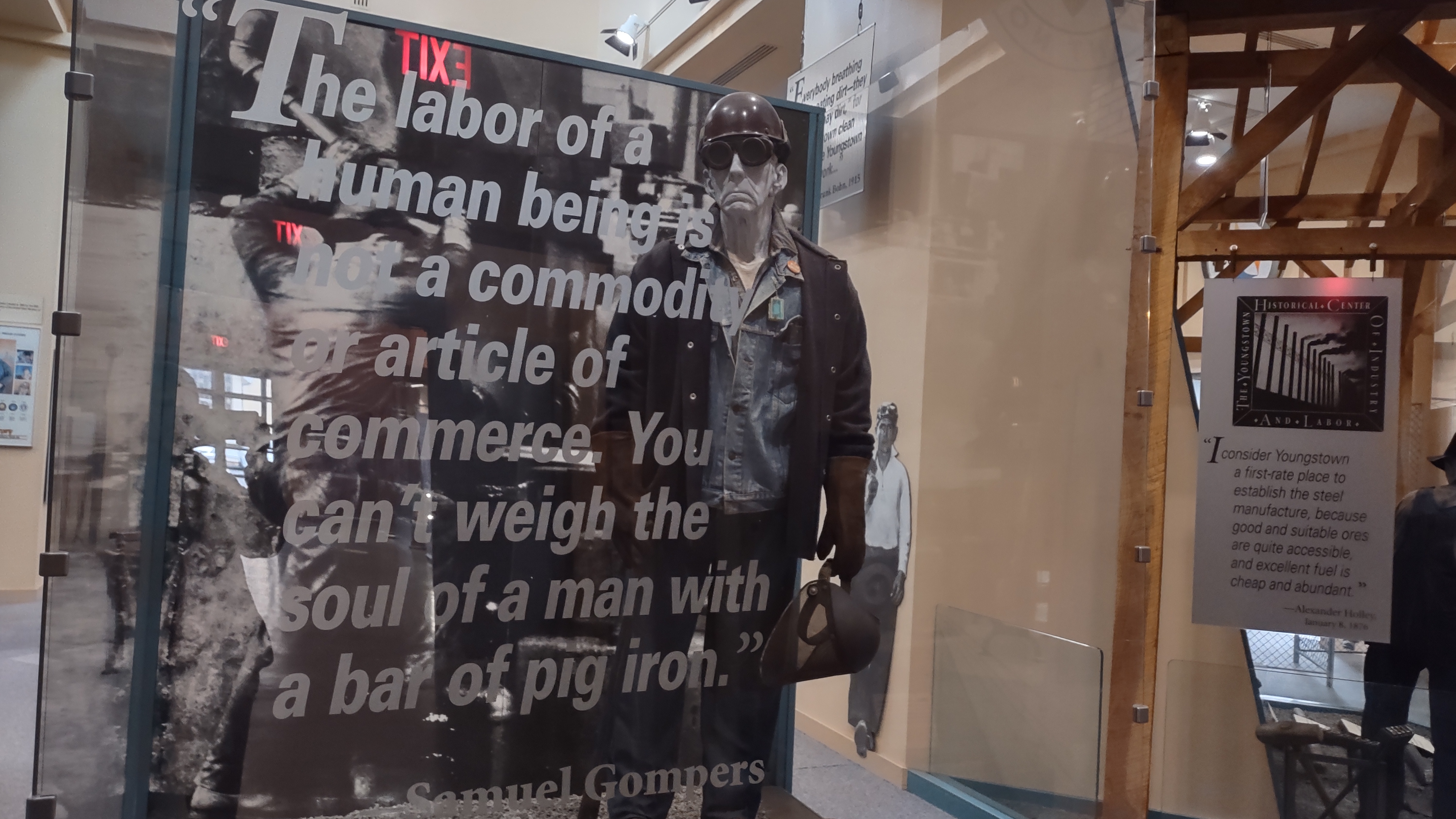

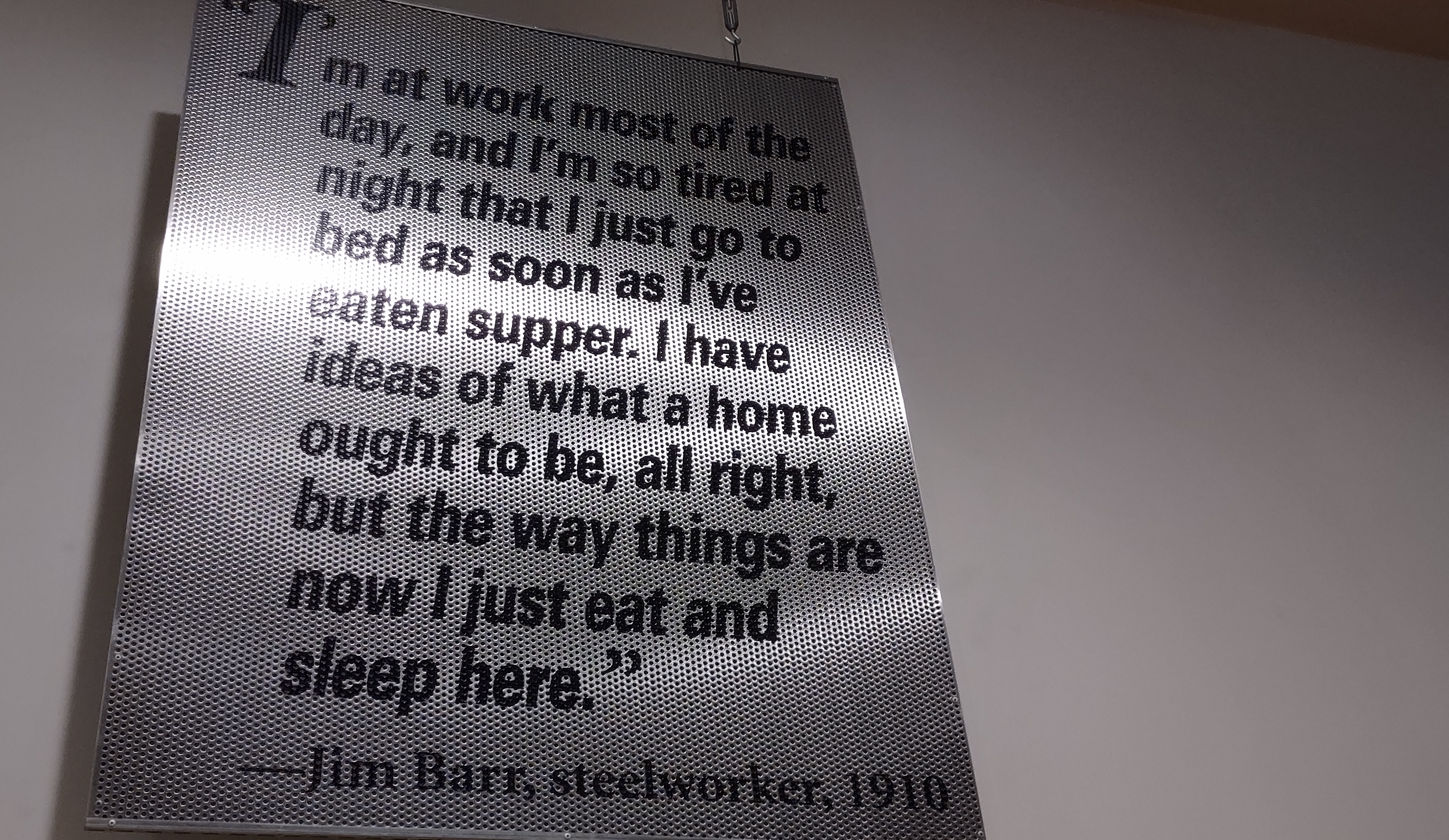

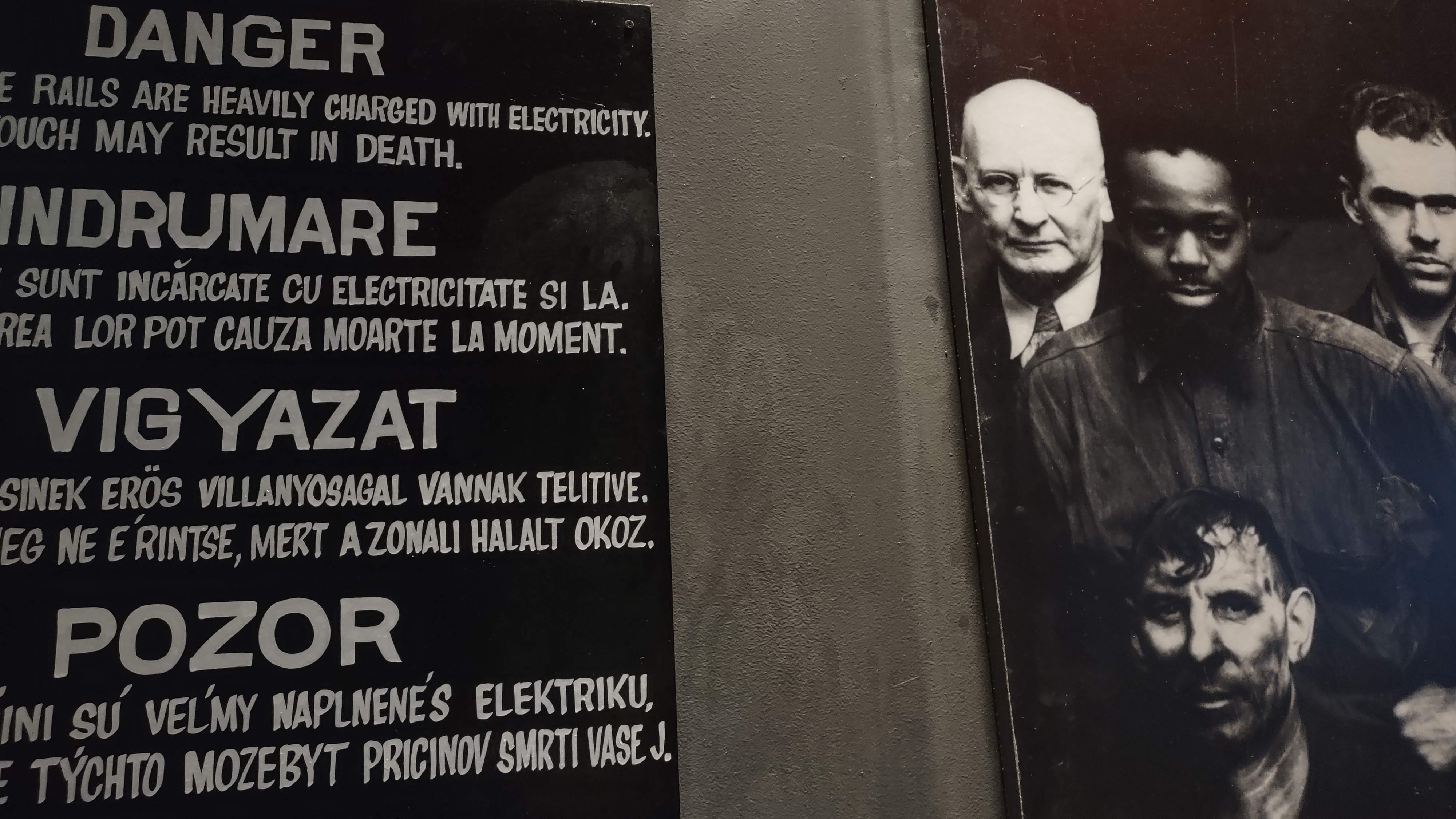

Labor turnover was high, as workers moved among steel companies, seeking better situations for themselves and their families. Poisonous gases, rapidly moving machinery, and 2500 degree molten steel made every day a hazard. Families lived in single rooms, huddled around the steel mill, without running water or transportation.

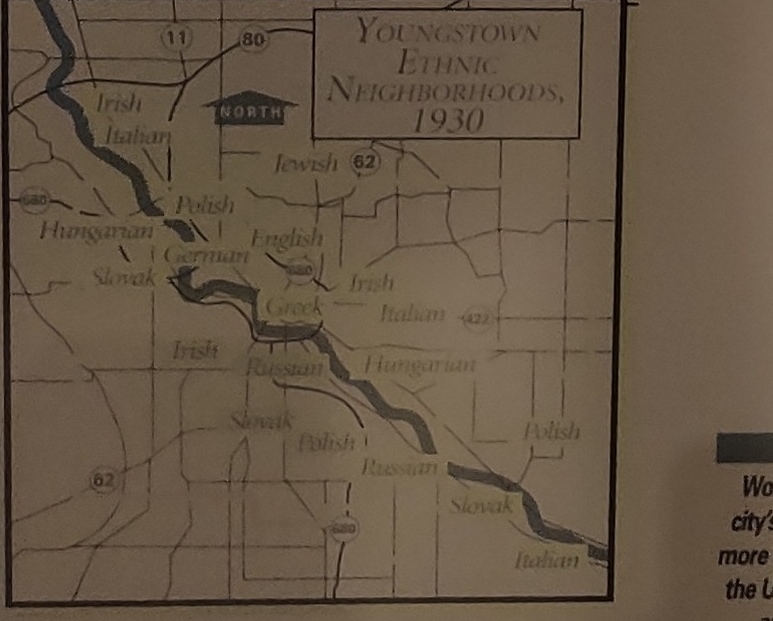

Company real estate officers controlled rental housing and home ownership, increasing leverage over workers. Ethnicities were carefully separated in company towns and job levels. Managers were English, Irish, Scottish, and German. Workers were Black or eastern/southern European.

Investors backed managers who directed the whole community in order to increase profits. Eventually only large firms, able to combine a variety of production methods and get it to the cities, were able to survive within the shark-eat-shark paradigm.

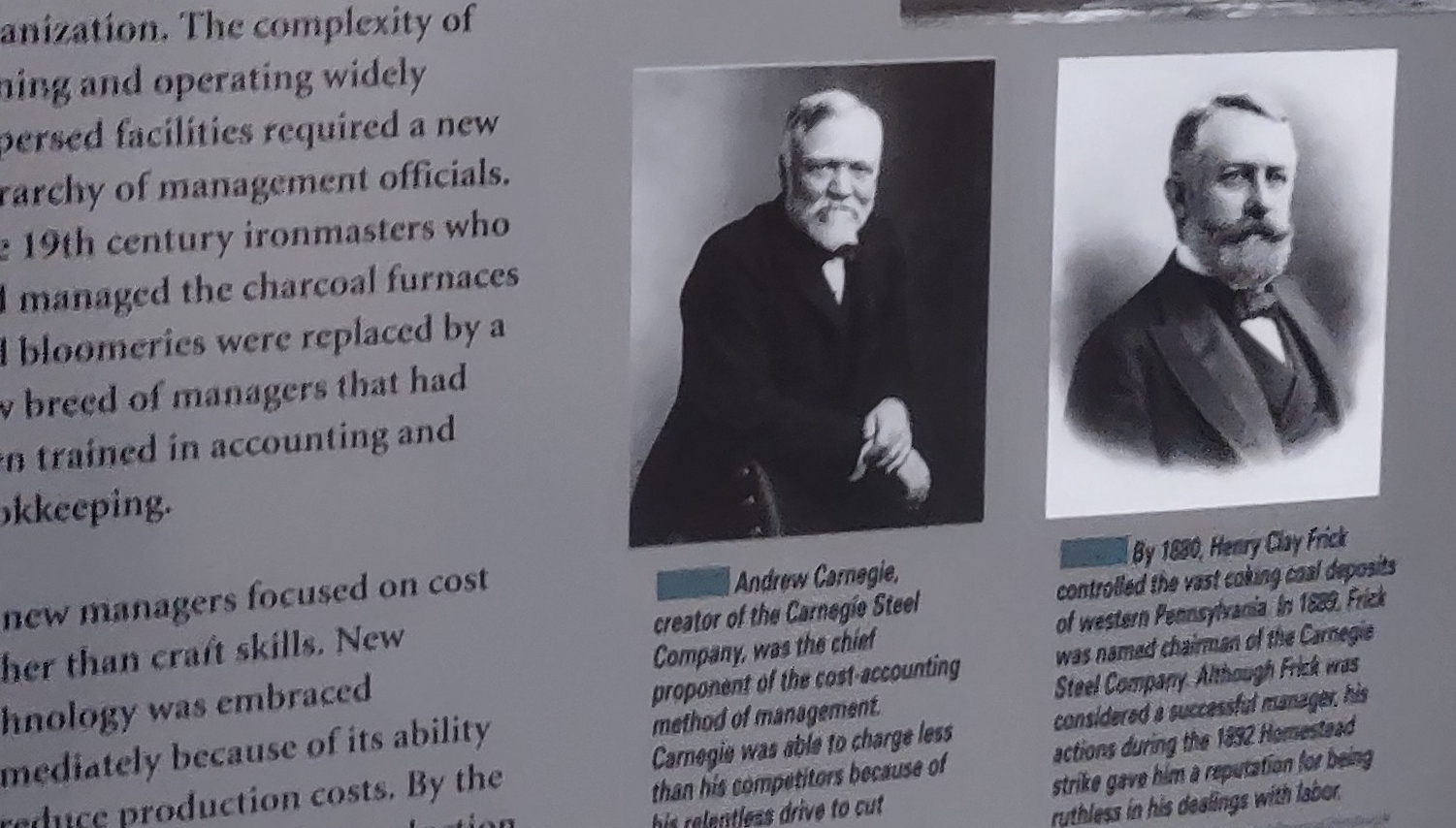

The Carnegie Steel Company was the first to tie cost accounting to technology, in an ever greedier grasp for profit. Technical managers applied scientific principles to steel production, creating many new steel alloys and finally, stainless steel. This relentless drive to cut production costs undercharged competitors and made Carnegie wealthy, like Amazon drivers delivering profit to the guy at the top.

Consolidation of many small steel producers through cutthroat competition created the industrial giant United States Steel Corp in 1901 (sold to J.P. Morgan who created U.S. Steel) with capital of over a billion dollars, and a vast network of blast furnaces, steel works and rolling mills.

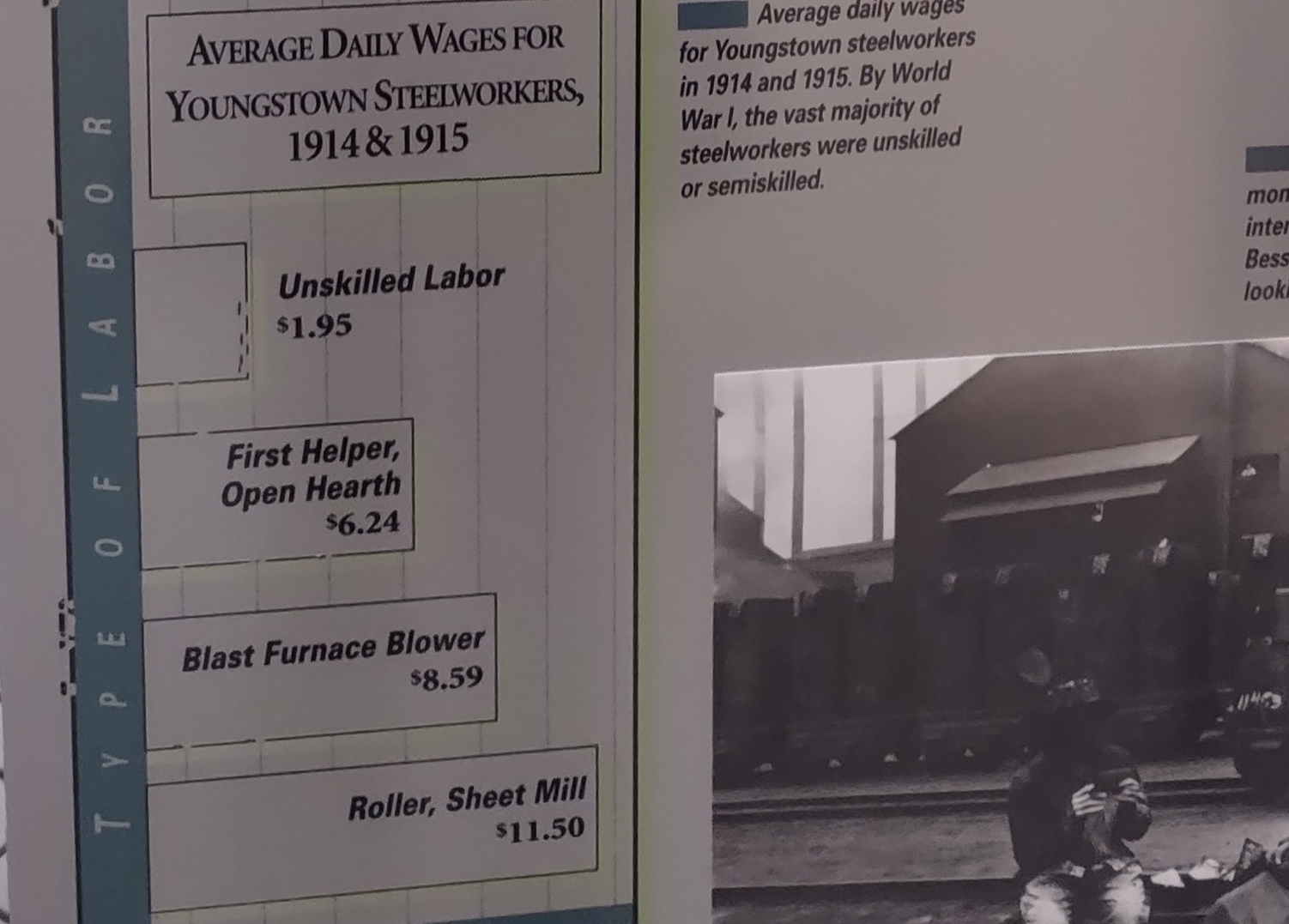

By 1914, the nation’s industrial growth rested on a large, efficient steel industry. WWI became to steel what the pandemic achieved for internet commerce. Several publicly held corporations produced a volume of steel to match the appetite of the public market, on the backs of factory laborers, delivering profits as steadily as black Amazon vans.

Hundreds of workers lost their lives each year in US steel plants, while thousands more were injured or disabled, as common law held that workers, by entering the plant, assumed liability for injury. Not until 1950 would fully protective regulations and workmen’s compensation offer relief.

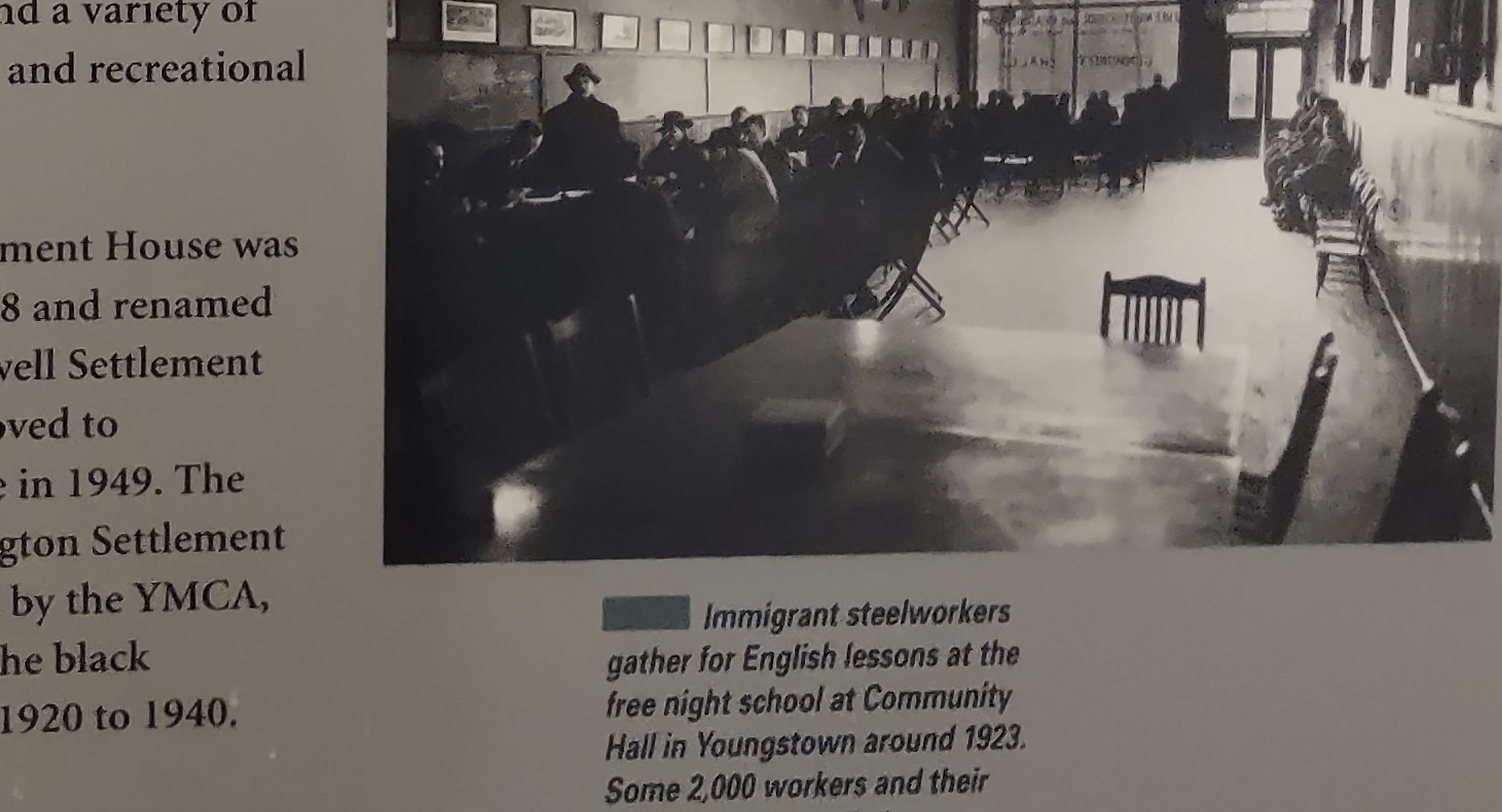

By 1915, a deluge of immigrants brought Youngstown’s population to 50% first generation. The mid-1800s brought Welsh, Scottish, English, Irish and German workers, who dreamed of land ownership and the restless search for something better. Italians and Greeks followed 50 years later, with Eastern Europeans close behind.

Black immigrants from the South were recruited to fill labor shortages left by WWI. Duplicating the rise of cotton’s demand for coerced labor in the 1800s, the rise of steel became a perfect storm for labor exploitation.

Community groups organized classes, for language and culture lessons, for thousands of immigrants, who formed their own churches and social groups. As descendants fanned out across the state, the rich mixture of cultures created an ever-changing Ohio identity.

A sea of rising humanity prompted 1916 riots to protest lack of housing. Republic Steel and Youngstown Steel, both part of “Little Steel,” which produced specialized steel products independently, adamantly opposed worker unions.

The battle raged between labor and management, as unions sought to win the trust of laborers, and management fought viciously. In June of 1937, workers demanded collective bargaining rights over work conditions. Company managers armed themselves and the police with tear gas, revolvers, shot guns and machine guns. It would not be until 1942 that the United Steel Workers of America would emerge.

By the late 1960s, declining demand, aging facilities, foreign competition, and smaller production facilities were spelling the sunset years of Youngstown steel. Because of harbor access and auto factories, steel production moved westward to Indiana and Chicago. Labor-management conflicts, obsolete technology, depletion of ore, and the new plastics market slowly strangled output.

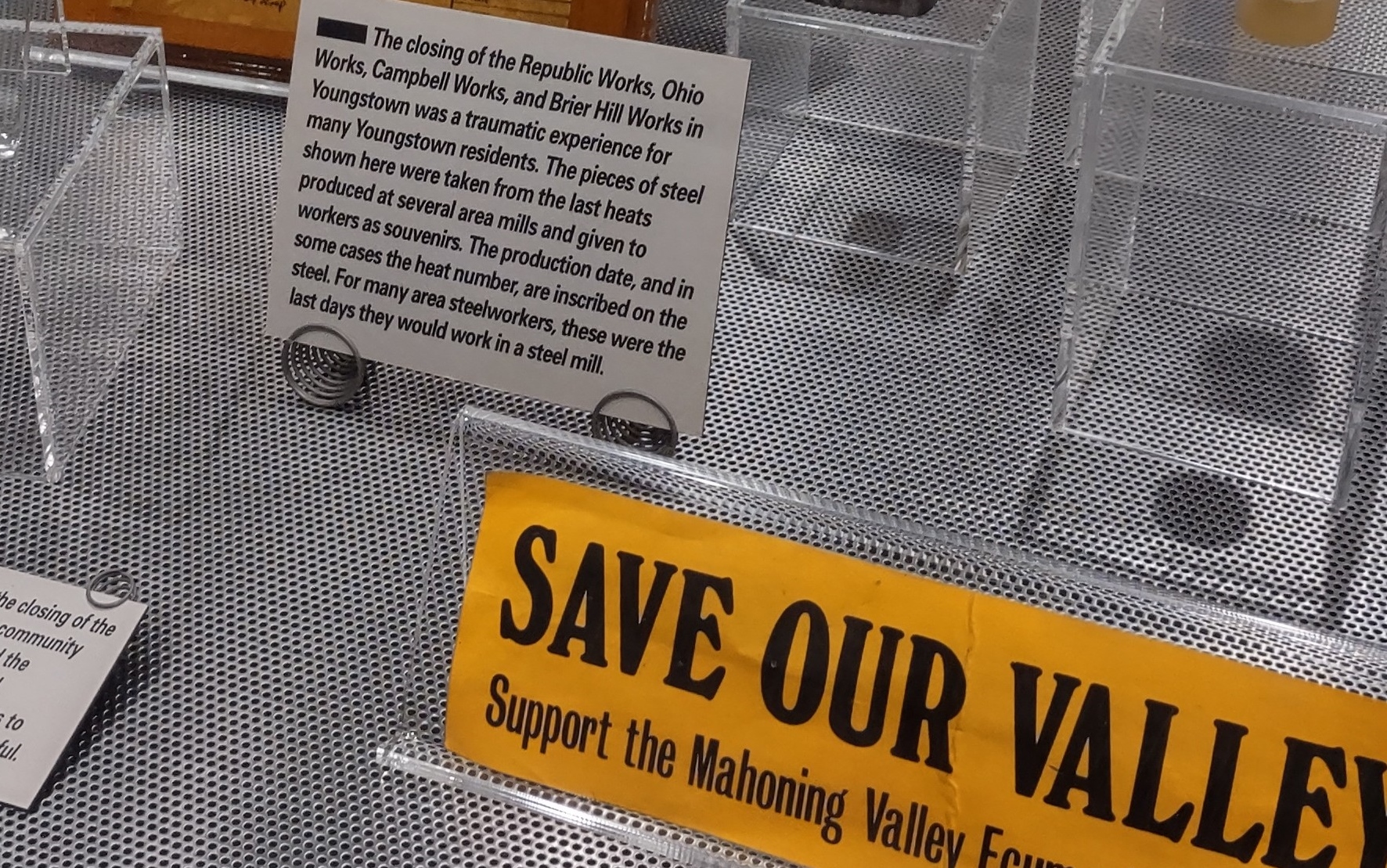

In 1977, Black Monday began the closing of five major steel plants and loss of 25,000 jobs – stockyards, machine shops, powerhouses, carpentry and print shops, repair shops, blacksmiths, and office buildings.

Shock reverberated throughout the Valley. Forty-five years later, the recovery continues, as the proud history of the steel mills that built a nation is remembered with respect and gratitude.

With tender detail, decades of dedicated service fill the lockers left behind.

As we step outside, a gentle drizzle falls. At Ground Zero, two steelmakers are immortalized. Across the street, the faith that sustained through years of turmoil.

The open hearth furnace sculpture recalls untold memories of lives spent. Someone has moved the cache a teensy bit high.

Slowly the water bucket fills with fresh rain.

-

Candykids lost in the city

In 2004, as Cache Owner candykids left a trail of breadcrumbs, Facebook launched. Now turning 18, FB claims nearly three billion monthly users. With zero marketing, and only fresh air to build followers, our just-turned-18 cache proudly parades 427 visits, signed with pen and paper, leaving keyboard and mouse hopelessly helpless.

We turn northward, as clouds curdle darkly, dripping a day drenched in drizzle.

For several long hours, cloudbursts skirmish with foggy vapor to swallow our trusty Civic. The dashboard battery light flashes like a heart monitor, then steadies and disappears. We follow the smile.

The exit dumps us from a north-dunking deluge to an east-dunking deluge. Rivers have changed from south-flowing to north-flowing. Sky water is on a one-way street, straight down.

Exuberant as Jonah spit out by the big fish, we land in Youngstown, teetering on the northeast edge of the state. Far above is the Youngstown State University sign.

YSU promises ambition, determination, innovation, and a promising future for its 13,000 students. With 45 years of turmoil from the shuttering of iron, steel, and auto plants, the challenge of rebuilding on the shoulders of technology enterprise is real.

Across the way, the old Presbyterian Church is now a Cask House, but the menu is the same – come as you are, and be yourself.

At Ground Zero, a congenial puddle-walker whistles the blues. Cache logs record travelers crisscrossing the country, hopping over from I-80 to play this national sport.

It’s a good day to be in Youngstown.

-

Wapak River swag attack

Our last venture northwest will take us directly to Wapakoneta and the Auglaize River. Cache Owner mattyice85 has placed a swag attack in a secret childhood fishing spot, when timeless, sun-filled days yawned and stretched.

A road crew battalion slays rebel asphalt and reconnoiters.

Far-flung fields wait for the little guys to fix the Big Guy. Sunlight suffuses cartwheeling clouds.

Neil’s farmboy grin welcomes us to Wapak. From this soil came the first human foot to touch the moon. Centuries deep beneath the ground, those wandering, invisible roots still hold and nourish the towering tree above.

Our geotrail detours to get the Mars update at the space museum. Humans dream and race to see who will be the first Christopher, Orville or Neil on Mars. Engineers revel in the novel challenges of entering a completely hostile environment, and designing machines to conquer it. Meanwhile, shuttle astronauts long for showers, pizza, ice cream and all that is quintessentially bound to their home planet.

As plasma is shot into rocks, ground surfaces are drilled, and trash accumulates, humans search for new sources of capital to ship back to Earth. The best minds in the world focus on flying rockets to distant barren lands, an easier task than that of inventing, reinventing, patching, and repairing the failing engines of communities around them.

That’s enough update. Weeping willows on the Auglaize take us back to peaceful placidity on a perfect afternoon, where average Americans do the reinventing and patching.

Stylista treetops preen in their watery mirror. Fresh waterways across Ohio contain critical habitats for filtering and maintaining water quality. Like oil in a car engine, as the water quality deteriorates, so goes the water cycle. Here the dumpsite has been dismantled, leaving a warning epilogue.

Summer’s leftover green refreshes. Discovering a faint geotrail, a large rock, and a deceased feline finally lands us on a waterlogged container.

The log shivers damply. We drop in a small, watertight micro.

With gratitude to our cache owner, we soak in the beauty of our planet and all that sustains it.

-

The way they used to be

We will set our coordinates for Wapakoneta, hoping to discover, from Cache Owners mrb400 and cmgclone97, the way they used to be.

Fields of corn advertising LG Seeds herald the brave new world of gene editing of food crops. As the Billionaire Boys buy up farmland, their gene experts cut and paste DNA into existing plants. Mistakes and accidents morph into super toxic plants and allergens.

Or perhaps a super-sized road android.

Ground Zero bears witness to lifetimes, chronicled in stone.

Inscriptions follow us through the cemetery. Georg died at 22 and Andreas at 17, in this very German Ohio settlement. The resilient, optimistic individualism demanded by frontier life coexisted with communal grieving. Careful carving quantifies the invisible distance between hearts, forming letters into silent, soul-crushing meaning.

Gazing across the gravel path, with proud amazement at the strides made in waste water management, ancestors might also quake a little at the number of sinks, commodes, tubs, showers, washers, dish washers, and garden hoses needed to guarantee the happiness of their offspring.

Cache logs narrate their own history. The CO explains that the way they used to be, coordinates were approximate. A great geocacher used their geosense to study the area and investigate different possibilities, imagining the mental game plan of the cache hider. Accordingly, this hide may be concealed as far away as several hundred feet from the given coordinates.

Cachers in 2010 navigate the way they

used to be, without a hitch. By 2012, there is a sea change. Loggers pointedly point out that the coordinates are off by 227 feet. Finally, in 2013, the CO zeroes the hide onto the coordinates, ending the conversation.

Have we finally uncovered the secret as to why some caches are still 227 feet off . . . ?

-

SQ Keller/Saint John Lutheran Cemetery

Placed earlier this year, Cache Owner Nickoli_1975 directs us to a cemetery cache, where SQ Keller shares top billing with Saint John.

As we meander northwest, the complex business of corn and soybean harvest assembles in the driveway. Chemical field treatments waft into our open windows. Tangerine-shaded trees hail the season of pumpkin orange.

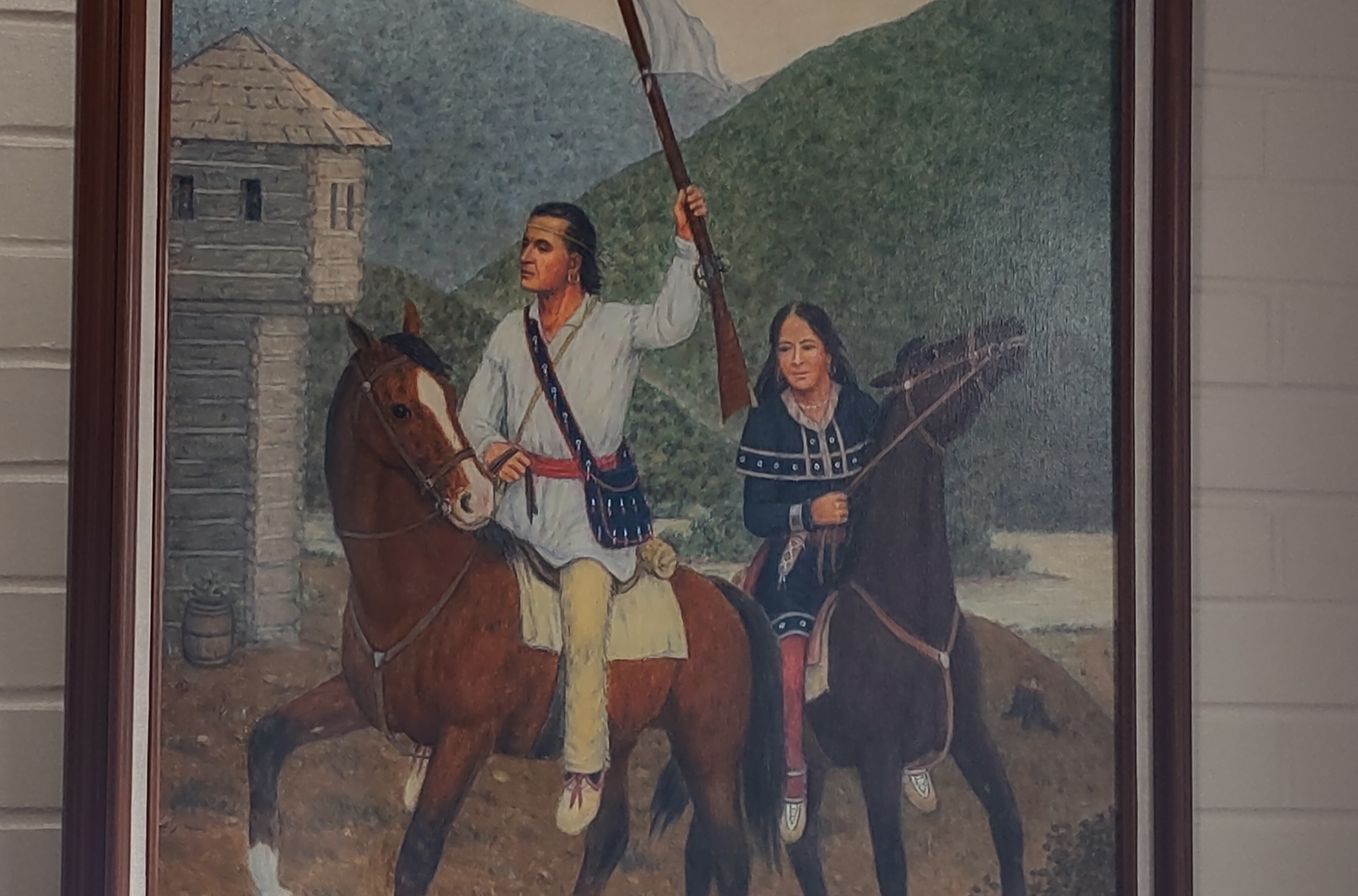

We pause at the Black Hoof Memorial Park. A veteran of the French-British wars, the Revolutionary War, and the Northwest Territory wars, Black Hoof fought with the French against the British, and then joined the British. In 1795, defeated by Anthony Wayne at Fallen Timbers, he put down his rifle and signed the Greenville Treaty. True to his word, his tribe did not join Tecumseh in the War of 1812.

Chief Black Hoof led the Shawnees in adapting to individual property ownership and farming, believing mutual respect could allow two nations to exist side by side. A year after Black Hoof’s death, rather than accepting American citizenship, the Shawnees moved west.

Today’s land dwellers peep over the ridge, navigating the same bewildering waves of change as the man honored here.

Our GPS moves us to a cemetery down the road, where we will drive into a field to reach Ground Zero. Centuries-old stones keep watch over the pastures and fields, immortalizing the big families who were cities unto themselves.

Offspring have moved into the digital age of urban sprawl, working now for those who have money. Spaces immense and free give way to middle-class subdivisions. Stones crumble, leaving cryptic messages behind.

Safe within Lutheran taxonomy, questions of individual salvation seek reassurance. Our graveyard celebrates freedom protected to pursue these questions.

We tramp through bristly fence overgrowth. Wooden posts transcend the cyber version, as wind whispers and sunshine soothes.

Baby Cache, only three months old, may you live a long life within your new geocaching galaxy . . . .

-

Welcome to Wapaghonetta!

With this most respectful of names, Cache Owner cccf1 placed a cache in 2017, on the bicentennial year of the Treaty of the Maumee Rapids.

In this treaty, representatives of six tribes relinquished claim to 4.6 million acres of land in northwest Ohio. The Shawnee were then confined to three tracts of land, one being a square of ten miles on each side, around their Council House at Wapaghonetta.

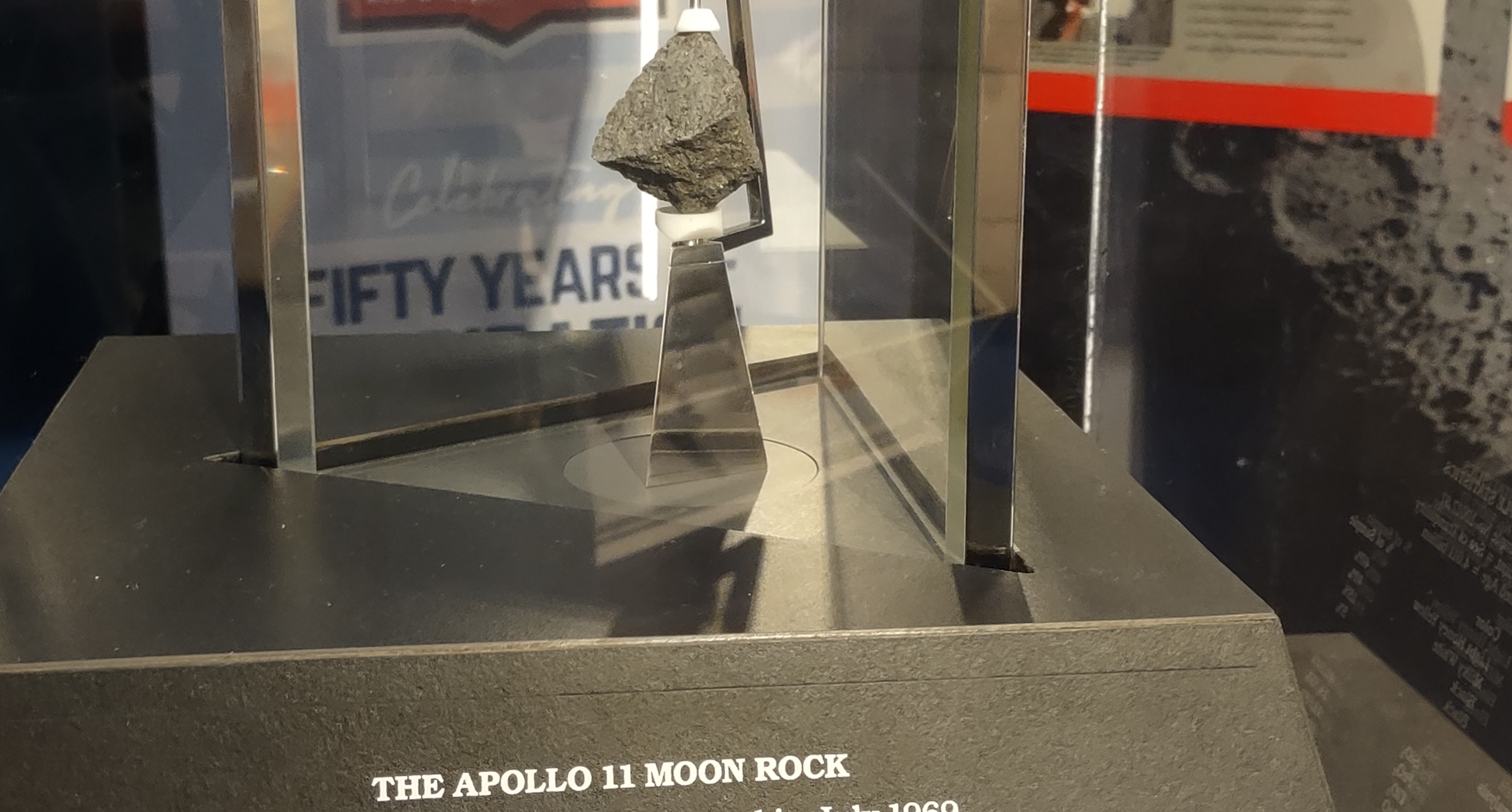

Now this is Space Country, where native son Neil Armstrong extends a hometown welcome. Inquiring minds nudge our geotrail through the Space Museum.

As WW II ended, Americans faced off with Russians across a divided Germany and a rocket missile race. Declaring that they must save the country and the entire Free World, politicians launched NASA, along with hundreds of thousands of jobs and billions of dollars. Technology, engineering, and computers rushed to the challenge. While civil rights and South Vietnam simmered toward a slow boil, the national debt spun into high gear.

Dozens of Ohio companies would cook up innovative products for the first Gemini missions. Heat shields, space suits, parachutes, fiberglass, space kitchens, batteries, mobile quarantine — the new shopping list was galactic.

In a long series of firsts, Americans entered space, orbited the earth, docked two rockets in space, sent camera probes and landing crafts to the moon, landed a man on the moon, and drove the first moon car. Optimism and adventure distracted from the clouds roiling darkly across the nation.

Dwarfing the humans who built it, the Saturn V rocket carried Apollo 8 around the moon. “Magnificent desolation” gazed upon the Earth of Genesis 1:1, a verse recited by the astronauts as they struggled to grasp the beauty of their planet. Suddenly, the measureless resources which fueled the mission reaped a massive public harvest, of environmental responsibility for an irreplaceable Earth.

Flying Apollo 11 in 1969, a Navy test pilot manually parked two humans on the surface of the moon, with the immortal announcement, “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” Five more Apollo missions would land on the moon, at a cost of today’s $257 billion. Like Lewis and Clark, mission specialists obtained rocks, surveyed ground, and faced hair-raising adventures to tell the folks back home. Unlike Lewis and Clark, the astronauts found no abundant forests, no sparkling rivers, no rich soil. And no current inhabitants.

Skylab led to the International Space Station. Space Shuttles ferried satellites into space, bringing space travel ever nearer to the (affluent) masses. Mariners, Vikings and Voyagers send pictures back from distant planets. Over 6,000 satellites now circle our planet, with a projection of 30,000 within ten years, occupying upper and lower layers of orbit. Ten per cent of the light we see will be from satellites rather than stars. Millions of pieces of spacecraft debris join the cosmic dance. Like French and British fur traders, the race is on to skin the most animals the fastest. Earthlings today see the night sky as it will never be seen again.

Outside the museum, we gratefully take a deep breath of naturally occurring oxygenated air. Our GPS pilots us to a closer Tranquility Base.

The plaque tells us that, along this fault line, runs the eastern boundary of the 1817 Maumee Treaty. Believing transformation would save them, Shawnees relinquished their culture of hunting and warfare, adopting the ways of farmers, carpenters, and mechanics. Shawnee children relocated from the woods and fields to school houses.

Around the prosperous Shawnee homesteads, migrants from crowded eastern states trickled in. Creeks of new settlers became rivers, and then a flood, washing everything before it. Vast cornfields, large houses, and abundant livestock, belonging to settled Shawnees, were coveted by the surrounding Wasichus, a Sioux word meaning “greedy.” As Shawnee youth turned to alcohol, and poverty overtook the tribe, leaders gathered the dwindling remnant of extended families for the inevitable journey west.

Black-topped roads, electric power grids, and rumbling vehicles now occupy the place of earth and open sky in the lives of the Two-leggeds. On this spot, the Cache Owner has connected us again with the ancestors who also loved this land.

On our way out, an eerie rollback to those vendor-induced addictions of 200 years ago. Global interests push onward with invisible yet invincible wasichu.

On the long trail homeward, the night sky, ever there, winks.

-

Choose Your Own Adventure

Cache Owner heather0013, placing only one hide, has nailed the fascination of geocaching. Go ahead and choose. It will be an adventure. And it will be yours.

Our adventure lies northwest, through the Month of Falling Leaves, over land preparing for a long winter nap. We hop off of Route 33 in Bellefontaine, our geotrail taking an unexpected loop through the Logan County History Center, and all that has happened on this spot over the past 2,500 years.

In our time lapse photo, we begin with the Adena, Hopewell and Mississippian Moundbuilders, far-flung civilizations rivaling the empires of Egypt, Greece and Assyria. Slowly we see new tribes moving southward and reaching this land, assimilating or eliminating the Moundbuilders. Next, as European explorers arrive, their armies follow close behind.

Superior weaponry and number of fighters, as always, will decide this conflict.

Chiefs sign treaties that will send them westward, where tribal embers will smolder and rekindle.

Into our time lapse pour untold numbers of immigrants, eager for cheap land and new business opportunities.

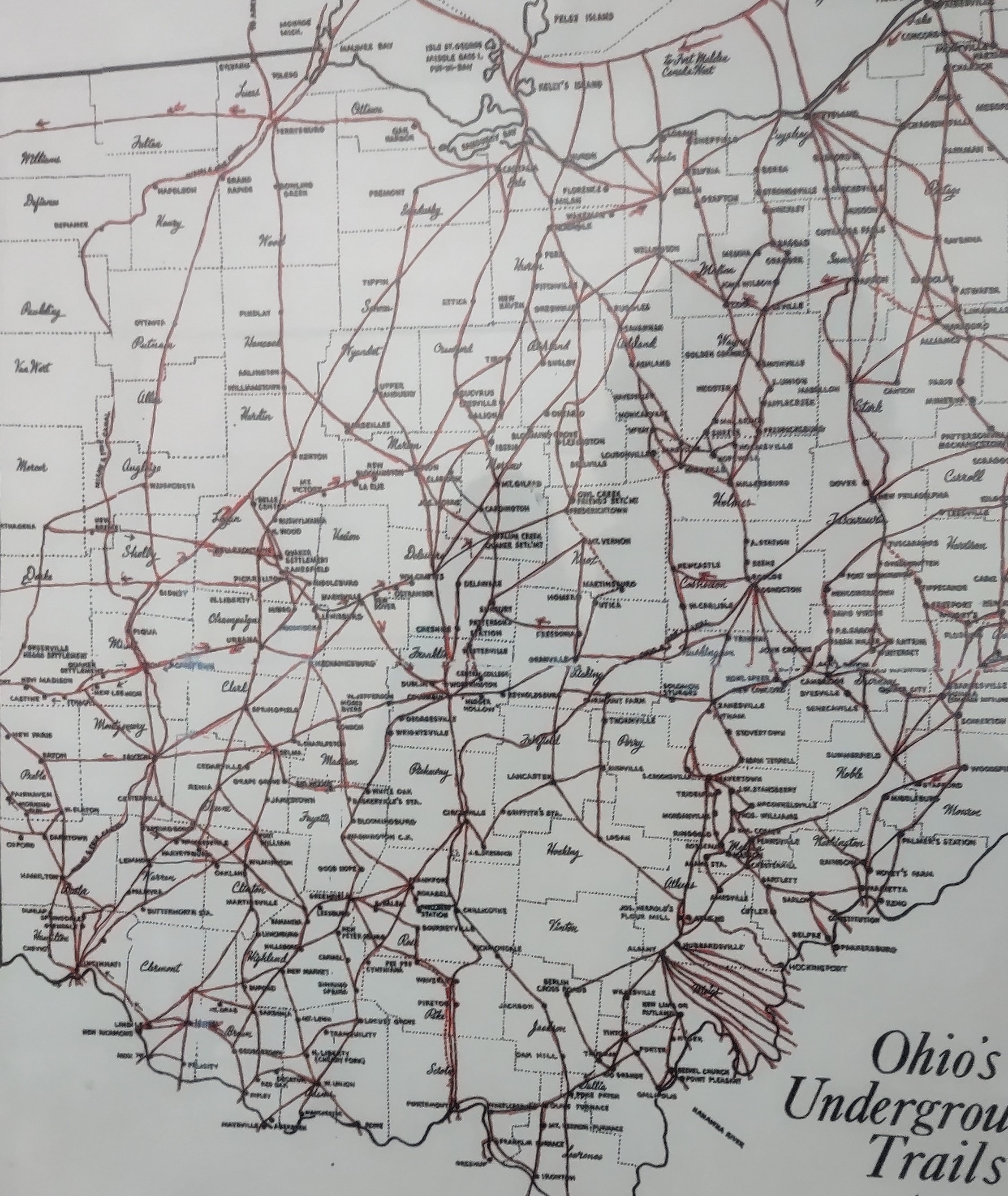

Local Presbyterians, Quakers, and college students pilot the Underground Railroad through Bellefontaine. Escaping Southerners are hidden in caves, secret basement rooms, and other unknown places enroute to Canada.

While husbands entertain bounty hunters in the front yard, wives whisk escapees out the back door. With the Fugitive Slave Law, fines or jail became a reality for people of conscience fighting human trafficking.

By 1900 the railroad terminal and crew change at Bellefontaine have also arrived, with hundreds of new jobs. Raw goods and farm products traveling east cross the path of manufactured goods moving to markets west. The resources of a vast continent will spend the next 100 years enriching those who can package them.

William Orr operates a profitable lumber business in 1900. He is finally able to build his dream house. It eventually becomes a nursing home. When the History Center decides to take over the property 75 years later, it is dilapidated, and the five resident raccoons are evicted.

Inside the mansion, our tour guide hails from an Amish settlement nearby. In living color, the power of religion across this land speaks. We sense the tension between personal determination of beliefs, and submission to rule-making authorities, between the free expression of generous faith, and the tightly-held strongbox of self-enrichment.

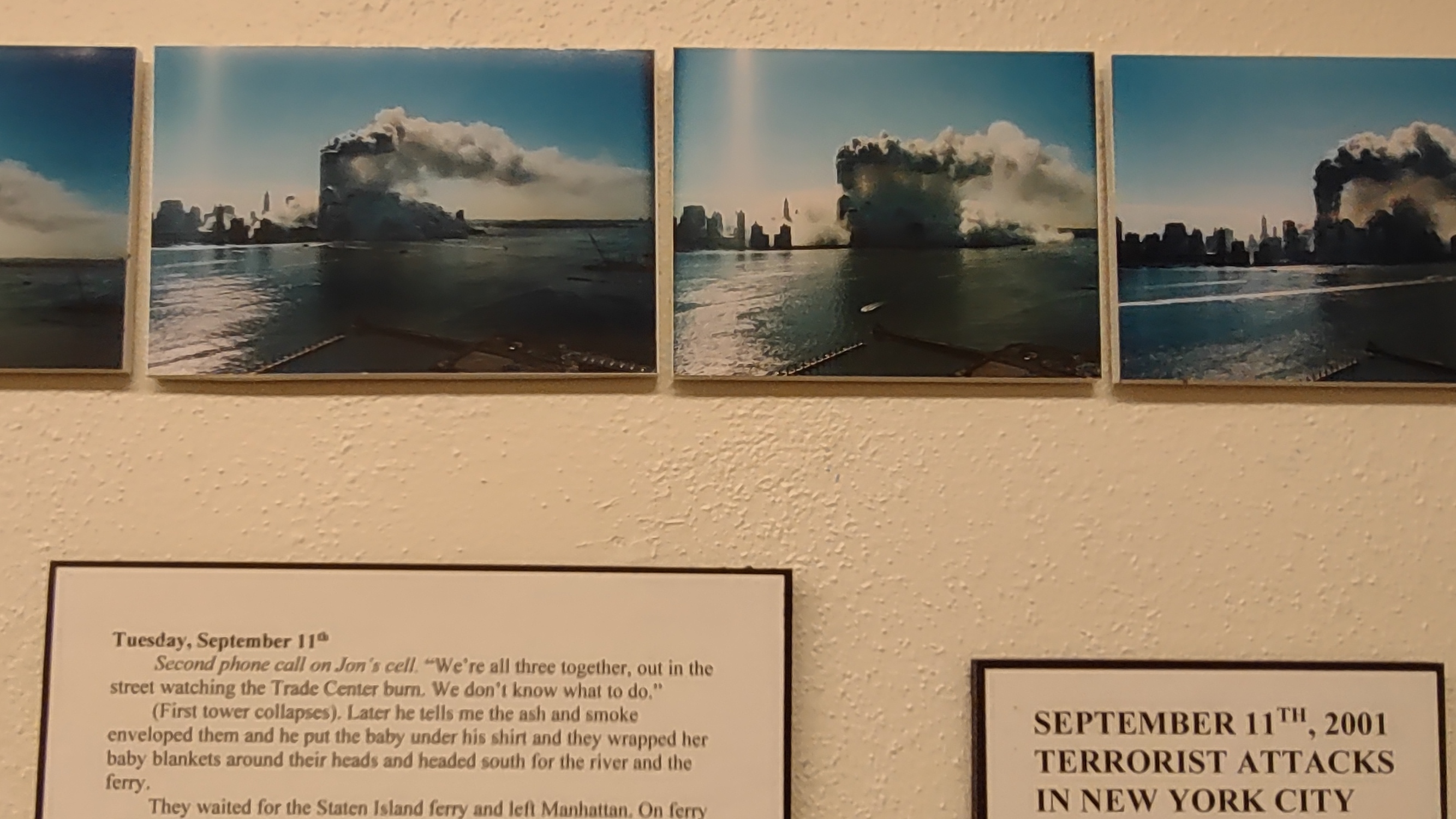

Our time capsule jars with a final picture, of heroism in the midst of horror, never forgotten.

Ready to resume our own adventure on this land, we follow our pilot to the northwest corner of Indian Lake, to a quiet street pungent with unspoken epochs of days gone by. Leaves crunch underfoot.

And we’re ready for our next adventure.

-

Just another brick in the wall.

Cache Owner steinman17 calls up Pink Floyd’s immortal classic, and threatens to unleash a group chorus of “We don’t need no education!” This is only slightly less alarming than the cache description: Placed while on a pontoon boat . . if on foot, you can only feel around for it.

Taking Route 33 northwest out of the city, we join the morning rush of moms hauling kids to school, early Christmas shoppers heading to out-of-state malls, nurses coming home from the late shift, 4x4s refusing to morph into a mudless urban environment, and road crews doing what road crews do.

Flashing by is the Honda Auto Plant, building vehicles for 45 years, now planning a $3.5 billion investment for EV battery modules. The prototype for agrarian American labor, Honda Auto built a dynasty on rural workers who, like the cars they create, are durable and high-performing. Roadways and parking lots wrap the globe, transporting these motorized shells of human turtles, defining the shape of human existence.

Our coordinates land at Indian Lake, drained from wetlands 150 years ago to feed the canal. The amusement park built at Russell’s Point on the lake delighted families for 40 years, until Cedar Point and King’s Island took over the theme park audience.

Blaze of sun on lake restores harmony drained by city vibrations. Fall flames on favored foliage, while shorn shapes shiver.

A question of who will go and where they will go begins to emerge.

The team holds together, in the thrill of problem-solving and possible plunging.

Thirteen years after first placement. It. Is. Still. There. Like the roar of fans in the Shoe, the sound of all who have conquered this cache is electrifying.

-

County Heroes 2

Ten years ago, Cache Owner kelitha8 placed County Heroes 2, warning us that we may get a little sappy.

Dry weather produces an encore of brilliance on the northwest route to Bellefontaine. In the unseen cosmos, celestial rotations unfold the goodness and beauty of autumn before our eyes.

The business of harvest is well underway. Heavy equipment on farmland crushes the life of the soil, escalating the spiral of chemical fertilizers. Rural dwellers struggle with respiratory exposure to pesticides in the air they breathe and the ground beneath. Small farmers utilizing sustainable methods call soil back to life.

Our coordinates take us to a quiet spot where, 40 years ago, a monument was placed. On that day, the end of the Vietnam War was still fresh in memory. By 1973, over two million men had been drafted. The number not returning was 58,000.

As viewers watched the new comedy M*A*S*H unpack the horrors of war, public rejection of the draft solidified. The industrial war complex moved toward technology and equipment to keep contracts flowing. In the long overreach toward globalizing American power, Vietnam marches with Korea, Cambodia, Kuwait, Iraq, Afghanistan and Ukraine. In this corner, each life is marked and remembered.

Living trees welcome us to pause, meditate, and yes, get sappy.

The roll is called for those who come to honor these heroes.

Rest proud and know that your valor was not in vain.

-

Ebeneezer Zane Cabin

Following the trail left by Cache Owner mellpen 15 years ago, we hope to capture a moment in history from a faraway time.

On our route northwest, we pass the Zane Shawnee Caverns, purchased and operated by returning Shawnee tribe members. Across ethnic communities, we clasp hands, share strengths, and gifts, and space, and resources, with like-minded individuals.

Further down the road, Zanesfield, Ohio, population 194, overlooks the Mad River valley.

Here, the hardwood forests teeming with game, deep soil rich with nutrients, and a river connection to the great inland water network made it a Black Friday supersale for chiefs, traders, and surveyors. Like gold diggers in the Black Hills, farming immigrants staked out the land.

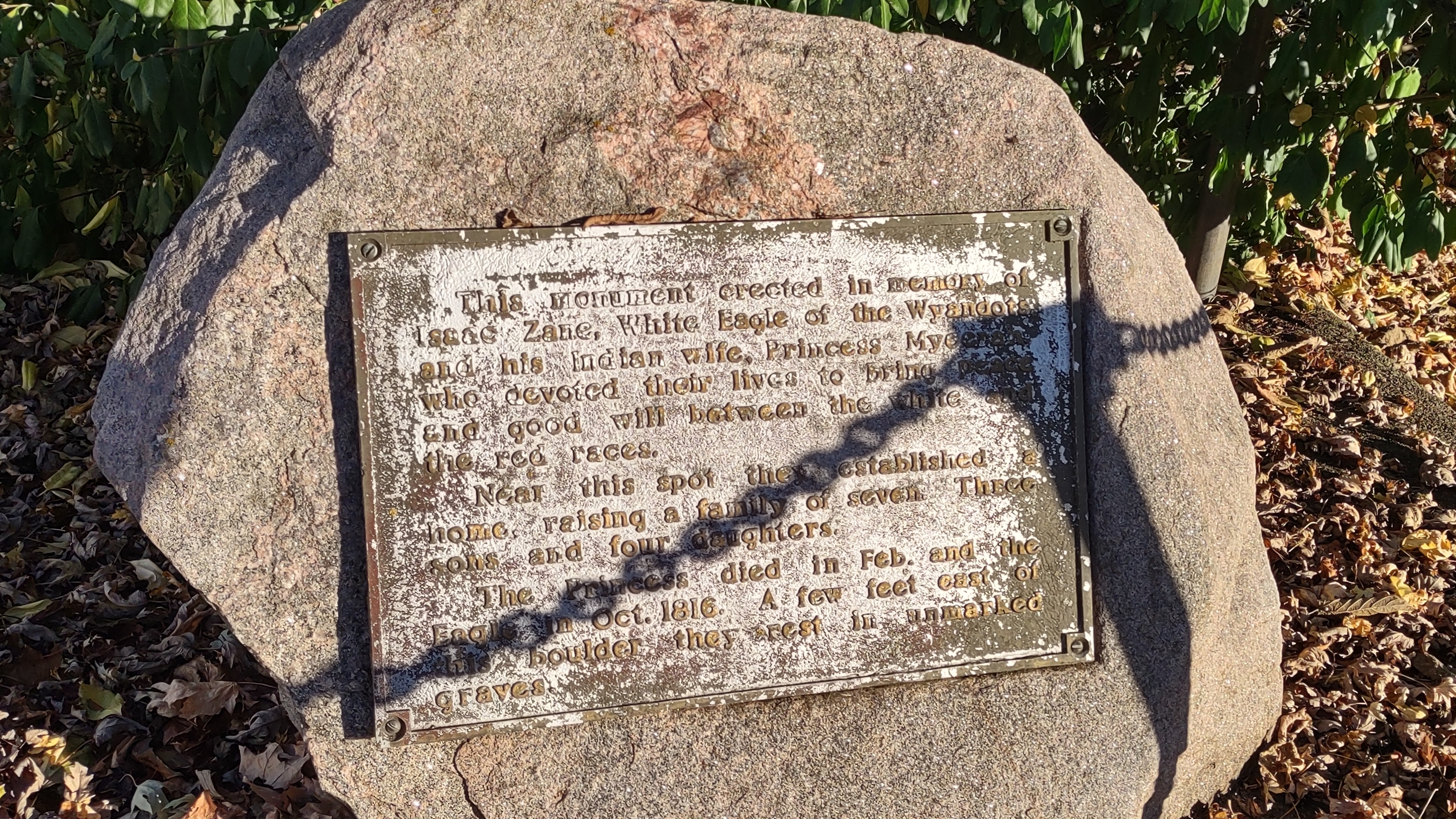

Tucked into a sleepy Zanesfield street is the Isaac Zane memorial. Captured as a child, he was raised by the Wyandot tribe and eventually married Myeerah, daughter of Wyandot Chief Tarhe. Friendly to captured prisoners, Isaac also served as a defacto spy, warning settlers of Indian movements. In an impressive display of bi-partisanship, Isaac was allotted land in Zanesfield by both Wyandot chiefs and the American Congress. Ultimately Isaac helped to broker the Treaty of Greenville, which would lead to the displacement of the tribe to Oklahoma.

Walk down the street and find the marker for the marriage of Isaac and Myeerah, where they birthed and raised their seven children. These children helped define the emerging shape of America, some descendants moving west and others remaining in the Ohio Valley, blending a sharing of tribal and immigrant strengths.

Myeerah’s father, the Chief, fought for the British army against the Americans, until Anthony Wayne defeated the combined army of tribes at Fallen Timbers. Chief Tarhe faced the choice of all tribal chiefs, to oppose to the death the newly born American army, or to hope for survival on the side of the Americans. The long generations of honor and valor, which demanded war dances, scalpings, and revenge, did not easily end. But Chief Tarhe sized things up and joined the Americans. He fought loyally for his new ally at the Battle of the Thames against the British in Canada. The chief’s choice did not save his tribe from removal to the West. Conquerors, driven to claim and resell the next resource on the horizon, were unable to sleep at night until they sat alone at the top.

Our GPS lands us at the Ebeneezer Zane Cabin, named for the British/Irish immigrant Zanes, who settled Zanesville, and who were Isaac Zane’s other family. In his trilogy about the Zane family, great grand Zane Grey brings to life the decades of chieftains, pioneer settlements, forts, bordermen, and guerilla warfare in the Ohio Valley.

The marker tells us that, in 1819, the First Methodist Conference was held on this spot, with 300 settlers and 60 Wyandots in attendance. Exactly 200 years later, at the Methodist conference on missions in 2019, a chief of the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma spoke of the turning point that John Stewart brought to the tribal nation’s history, when John began telling the tribe of the Gospel story. John, a man of mixed tribal/Black heritage, was respected and admired by the Wyandots. Many found hope and peace from the destructive forces of alcohol addiction and warfare that defined their lives.

Across the road, today’s version of the one-room log cabin.

In this humble spot, buried under national and world wars, witnessing untold stories of heroism, affection, celebration, and compassion, we find a cache.

With a hat tip to our Cache Owner, and to all those who have loved this tiny corner of the earth.

Skip to content