-

The Urban Wild

Eight years ago, Cache Owners DianeAndSteven hid something wild. We will venture down winding asphalt trails and through stately rows of cement-bound dwellings to search for it.

Towers talk with south-moving traffic, relaying Earthling messages of blissful unlayering of gloves, boots, parkas, scarves, earmuffs, toboggans, mittens, and long socks.

Rounding THE university curve brings us past the slowly-appearing next gen of healthcare, an 800-bed deliverance of digital technology, connected to existing treatment centers for cancer, heart, spine, and brain. We opt for heart, spine, and brain engagement of a different sort.

Our exit lands us on a street so old, it’s brick. Brick runs down the street and up the steps and over the emotionless faces of German Village. Over two centuries, the hard-working and frugal residents of “die alte sud ende” have weathered anti-German war sentiment, the closing of breweries during Prohibition, and suburban flight.

Suddenly around the corner our first treasure appears, small but mighty among its towering neighbors.

Here city dwellers crowd to see the first buds of spring, feast on green-tipped prairie, and hear the warble of a waking nuthatch.

In the shadow of skyscrapers, Two-leggeds reach for play, connection to all that lives and breathes around them, and a refresh of undigitized faces – what? You still have legs?

The cache description advises us as to the delights of the Nature Center. As usual, our CO is not wrong.

The Treewhispers project dangles mysteriously. Here, participants share stories of their memories and connections with trees.

Like teardrops, each ring tells a story, stamped with the singular and precious thumbprints of an infinity of human voices.

New stories awaken with the Artist-in-Residence.

What this old guy knows, he’s not telling.

Our geomap pulls us outside, toward the river.

In amazing magnificence, the slightest tinge of emerald-flecked chartreuse peeks from a yawning, stretching monarch.

From each chrysalis, the tiny wings unfurl.

Last year’s wardrobe gets the memo. It’s over.

UNDER pressure? STICK around long enough and you’ll find it!! promises the hint. We start by looking down.

Seems to be a lot going on under. And there’s so much at stake. Here’s a stake. Was it a stick or a stake? Was it under or down? Stick that stake back down into the ground.

Tricky, cool, super interesting, brilliant — past finders tell us not to quit. Hiding in plain sight, a minuscule messenger winks.

Memories of trees float past, held within the smoothness of this tiny log in a log, and the drooping of the winsome watcher above.

Keep a green tree in your heart, and a singing bird will come.

-

Zion

In 2009, Cache Owner jaybirdchauffer sent out the marching orders. We join our fellow pilgrims in search of a beautiful place.

Following the geotour north on 23, signs of Goodwill and ReStore-ation spread the jelly of communal sharing over the peanut butter of those who have too much.

From Route 23 we find – no, not that guy – Waldo. Here the sound of marching feet echoes across two centuries, as the Wyandots of 1808 sign their tribal trail over to General Harrison. Parading along this road, his soldiers push back British and tribal troops in the War of 1812. By 1817, more elbowing will reduce tribes to tiny patches of northwestern land.

Only 40 years earlier, the Declaration of 1776 frames a paradox that will haunt tomorrow’s Americans. The Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God, on which revolution rests, will quietly question the relentless and ruthless Pursuit of Personal Income Happiness.

As Mr. Darwin of 1859 reassures that survival of the fittest is perfectly natural, 29 million acres of woodlands and plains fall to the strongest, fastest, and richest. One acre of Ohio forest survives untouched in every 29,000 acres of not-the-fittest. .003%.

Watching over those names who have fallen in the struggle, shaggy bark and winter scarlet also recall fallen forests, and birds returning to nest, splash of spring waterfalls, delicate pink buds, woodsy scent of soil clinging to hands. As future mass casualties on far-away battlefields are resolutely opposed, cherished landscapes are also gathered into preserves. In turn, they gather a fragmented world and weave it into a coherent whole.

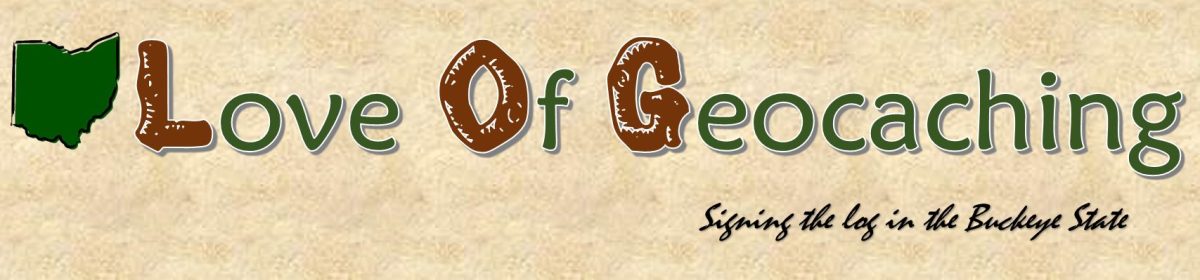

Just up the road from Waldo, the story of Bill Anderson begins. Across the fields of Marion County, shadows slip through the night. Of 100,000 shadows crossing the moat between King South and Queen Freedom, 40,000 pass through Ohio. Quakers, college students, Black communities, and others of conscience swirl the wand of courage and compassion, and fleeing Americans teleport north.

Hard-working Bill moves to Marion in 1838, offering his talents as a barber and musician. Hot on his heels, eight pistol-waving Virginians arrive to claim him as a fugitive. Judge Bowen calls a trial in the courthouse. The judge rules that the claim cannot be proven. Dragging Bill to the street, the Virginians demand a retrial with the local Commissioner. Bayonets are drawn. Quakers wrestle Virginians as peacefully as possible under the circumstances. Bill is spirited out the back door, still hotly pursued.

Twilight deepens around a rising moon. Now hunting both a story and a cache, we follow Bill south, leaving Marion for the last time.

Calling on that prehistoric skill of map-reading, we ignore the GPS and patch roads together to find our geo-zero. Safe within the promise of Zion, pilgrims journey through life aboard the great ship of the church. The woven tapestry of names traces bright threads of new lives born, and dark tears of anguished goodbyes.

Previous finders begin to speak through their online logs, “Is it a church with garage doors or a barn with stained glass windows?” The question troubles Cache Nation.

Nature and Nature’s God are entrusted with many small containers in out-of-the-way places, visited infrequently by wandering seekers. Finding this sacred space hijacked in the service of commerce makes the heart ponder.

Over time, as its economic value falls, religion slowly dims in the national deck of cards. The spades of ever-faster acquisition, alongside the clubs of cronyism, completed by the diamonds of wealth at any cost, squeeze out the hearts of individual connection to spiritual health and wholeness. Far above, the light shines through.

Gravestones keep wordless vigil. As the heartbeat of the earth winds down, nourishment of the Two-leggeds slows to a trickle. Lumber harvesters are followed by industrial farmers, coal miners, gas drillers and oil pumpers. Stepping up next in the long line of survivalists are the solar panelers, the frackers, the lodging and rental industry, and all 50 zip-line-canopy operators in the Hocking Hills.

From 230,000 miles away shines a beacon of grace. Gentle breezes calm and quiet. In this small space, ground remains as it has been for two centuries. Silence slips into our own sea of tranquility.

From the corner of Zion, a post calls. Branches, bare as bones, wave wildly toward the spot. Harvested hay hunkers down.

From the corner of Zion, a post calls. Branches, bare as bones, wave wildly toward the spot. Harvested hay hunkers down.

Now that the upper fence rail has been shoved to one side, and we realize the cache has fallen down into the post, and we’ve figured out which side to pull from, and we’ve gotten around the fence, it’s all so easy.

Madame Puss-in-Boots is okay with having visitors, and the strange games they play. But why isn’t anyone leaving a little canned fish swag?

Bill is not to be forgotten. From the back door of the Marion courthouse, he is spirited by the Quakers on a journey 20 miles south and east.

In 1812, the Benedict family migrated to Morrow County from New York. For the next 50 years, their burgeoning Quaker settlement smuggles escaping Southerners.

When Bill arrives at the Benedicts, the door slams shut behind him. The Virginians are arrested, fined, and sent back across the Ohio River. We pull over on a dark road, where the Benedict house still stands, framed in light. When we ask for stories from this refuge, about fear entering the front door and freedom leaving from the back, the wind whispers. You are free. Share it.

City lights beckon and pull us south, toward our own doors, and the safe shelter of warmth and food. Unexpectedly, colors of freedom cross our path, radiating the courage and compassion of those long-ago Buckeyes.

Watching and witnessing, weaving the waltzing whirl of earth and moon, rise the celestial harmonies.

-

Blockhouse P&G

A five-month-old baby cache hidden in a house of blocks sounds like a good time to us. We will follow Cache Owner hockeydaze to the nursery.

Along our northbound road march today’s version of the blockhouse, with another five acres ready to develop. Originating in Macedonia, the Stavroff name now attaches to law, design, and real estate.

Down the road, Ryan Homes is ready to serve, with we-build-for-you starting at $365,000. Tired and treeless farm land, long bereft of small creatures, calls upon the earth beneath to bear the weight of 240 tons of house per 1,500 square feet. Farmers weigh the cost of turning beloved homesteads over to public parks preservation.

As our geotarget closes in on Marion, brilliant blue above shames grass and brush competing for the Drabbest Shades of Winter. Trees, wake up and shape up. Get dressed! Go green!

Nobody listens. When we stop at Claridon Prairie, tangled masses of grass will not get their hair combed and sit up straight. They are wild things, rising and falling with each summer and winter, over hundreds of seasons, before Ohio was. Caught between road and railroad track, no one bothered to root them out.

Here the tribal nations, steeped in abundance and diversity, called themselves names such as Yellow Hawk, Dove Flower, Crow’s Nest, Morning Dew, Bluebird, Born on the Mountain, and Head of Creek, in their own languages. The world comes alive around us as we hear the names, and imagine all that is no more. Risk, danger, opportunity, and adventure now flatten to flickering images.

Today’s Two-leggeds wander across the prairie, in metal cages, on narrow trails of asphalt or steel, searching through glass for the wonder of pine needles, the joy of sun-washed air, the soothing serenity of silence. Across eons, the land beneath connects us.

Leaving the prairie behind, we admit we are lost, no thanks to our GPS and far-away satellite. We have circled five miles of country block and are still . . . nowhere. When we try to turn around, a friendly farmer indicates that this, and only this, field, is the one where he has intended to turn into all day long, specifically at the exact moment we are turning around. Yes, sir.

Well, there it is. And other unreported comments. We stand on the line of the Greenville Treaty of 1895, running from Cleveland south to Bolivar, then roughly west, where it passes over our feet on its way to Greenville. Pennsylvanians and Virginians made Black Friday look tame as they raced toward a super-sized land sale. This blockhouse was once a fort, now long gone, built to protect and reassure prospective buyers as British and tribal allies threatened war.

The scattered bones of a deer give eerie form to a past still hanging in the air, when Delaware and Shawnee guides found themselves pushed aside by those they had befriended.

The baby emerges, with many friends to play with. We request our playdate.

Time rolls back into the thousands of years. Here burial sites of Ancient Ones, as ancient as the glaciers, have been unearthed, with their distinctive spear points, ornamental shells, and red clay powders.

Like the image of grandmother in a beloved daughter’s smile, we catch a glimpse of what this land once was.

-

Can You Hear Me Now?

Fifteen years ago, Cache Owner hhhmmmmm proposed a riddle. Hmmmmm.

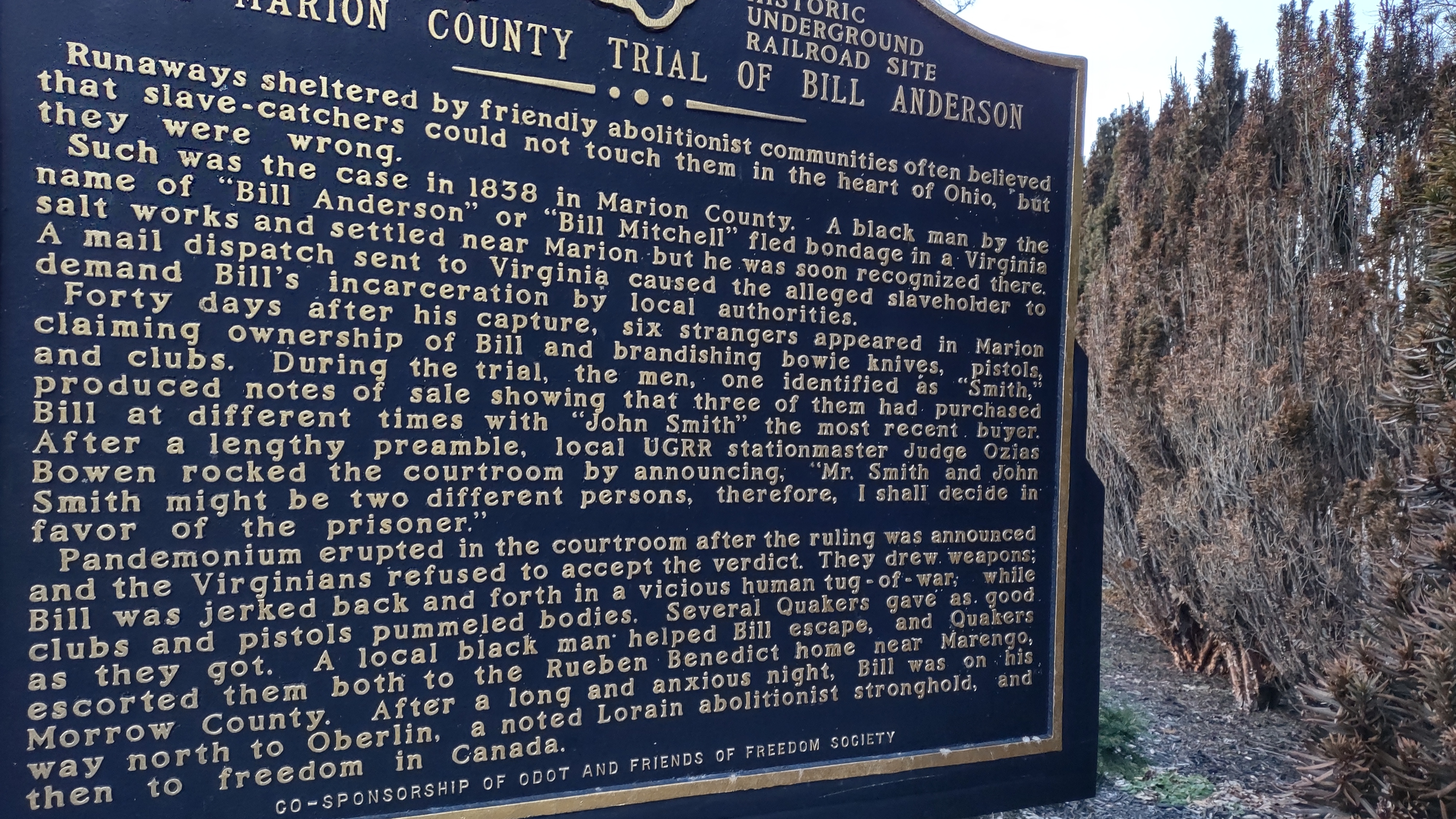

Our geo-zero lands in Marion, next door to the Harding Presidential Site. Starting with Mr. Grant in 1869, seven of the next eleven pairs of feet resting on the floor of the Oval Office would walk there from the soil of Ohio. Mr. Harding was the last, exactly 100 years ago. As Americans feel the need for law and order on the x-axis pull against the abuse of power for personal gain on the y-axis, the trajectory of Presidential influence rises higher and higher on the national graph.

Mr. Harding’s long years of unfaithfulness to his wife, his cabinet appointments obsessed with self-enrichment, and his restless hunger for changing the now to something-new-and-different will succeed in setting the tone for the next century of American politics.

Warren’s great-grandfather begins as a farmer, passing down his farm tools and his Bible.

By 1883, 19-year-old Warren owns a newspaper. As frontier grandchildren become literate readers, the potential for shaping mass national culture sprouts a seedling. In Marion, Warren’s newspaper pushes for street lights, city parks, and paved brick streets. At age 23, Warren marries a wealthy single mom, ready to back Warren’s newspaper business with her father’s hardware and real estate fortune. Ten years later, he is serving in the Ohio House and then as Lt. Governor of the state.

As the first airplane takes off, and the Titanic sinks, Warren wins a Senate seat, moves to Washington D.C., and takes over the RNC. After ten rounds of voting at the national convention, he is nominated as the Republican candidate for the 1920 election cycle.

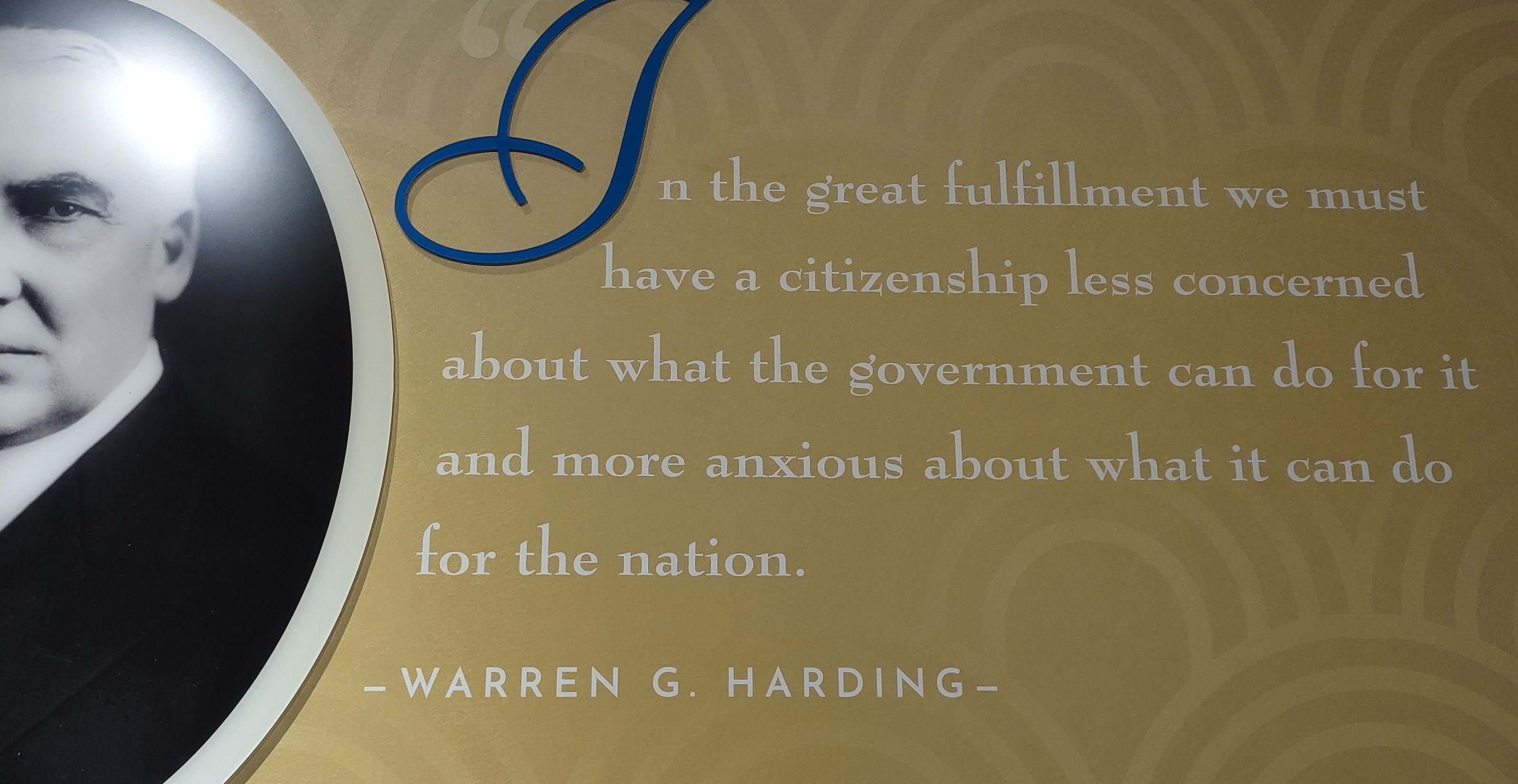

Following the examples of Garfield, Harrison, and McKinley, Warren runs his campaign from the massive front porch of his Marion home. It is the first Presidential campaign with large amounts of cash funding, professional advertising, and frequent celebrity fireworks. Movies and newspapers have brought actors, athletes, and military heroes into homes across the nation, as mass culture blossoms into a sapling.

Trains bring these influencers to Marion, twice a week, before an admiring small town and the eyes of the nation. Al Jolson tells the nation what to sing, “We need a man to guide us who′ll always be beside us, Warren Harding, you’re the man for us.”

As entertainers enter and leave the spotlight, their own personal connection to small town life is lost. Celebrity scriptwriters choose the next cultural boundary to bend and break. Warren gives love back to the hard-driving cultural elite. He agrees that people should not be told what to do.

In the election of 1920, city voters outnumber rural Americans for the first time. Millions of women vote for the first time. Warren wins in a landslide of electoral votes: 404 to 127. At his 1921 inauguration, Warren speaks into the first microphone, to an astonished audience of 125,000 who can hear him now.

Roads for automobiles, entertainment for war-traumatized Americans, aviation start-ups, and any new business idea you can think of fuel the rising stock market and relentless pursuit of wealth through the 1920s. The graduation of the letter E from electricity to electronic will take a hundred years. In 2020, electronic commerce, mail, drives, and all manner of Internet E’s wake us up to a brand new day. In 1920, electric motors, appliances, assembly lines, and ultimately radio and television transmitters launch a brand new planet.

Industry and government have no trouble seeing the benefits of turning the whole country into one mass audience. Rural culture will be reached and brought into the next wave of spending and boundary-shifting. Funding fertilizer pours into the roots, as our tiny seed of mass media grows into a full trunk, branching across a nation.

Within 15 years, two out of every three homes has a radio. Suddenly, if you don’t have it, you are behind the times. Talk shows, soap operas, games shows, sportscasts, and comedy hours bring families in from the front porch and backyard to sit at the feet of the far-away voice. Warren himself is the first President broadcasting live into the homes of waiting Americans.

In 1923, Warren takes a train trip across America to visit the Alaska Territory. Still recovering from an extended illness, he relapses in San Francisco, and there he dies. A shocked and grieving nation mourns the Presidential train as it winds back across the towns and farmlands, where his name was checked on their voting ballots.

The chair in the Oval Office is brought home to Marion. Firestone, Ford, and Edison join the line of mourners. A President who seemed fit and hearty, after the long invalid months of Woodrow Wilson, staggers and falls.

From California to Washington D.C., and back to Marion, Americans show up to acknowledge the Presidential office, and the fragile balance of power it holds over their lives.

We find the Harding Home and follow Warren’s footsteps across the yard. Visitors are still received, and still come, to learn and understand.

On the legendary front porch, we look for traces of footprints headed for the White House. Like Mr. Bush and the Gulf War, Warren’s star rose and fell with the tides of power and opinion. Stories of scandals during his time in office sprang to life after his death. A daughter fathered by Warren stepped forward. One hundred years later, W.G. would fit right in.

A national campaign raises $738,000 to shelter the body, in a monument rivaling Mr. Jefferson’s.

Mr. Hoover isn’t wrong. Our honor for those who have walked across our national stage is freely given.

Down Delaware Ave and across Barks Rd, our cache is in a Rather Natural Pile of Trash. Yes! We hear you!

Our TOTTs relish their role in the geo-enterprise.

Drying the tears of a lost cache and returning it home adds a warm feeling to an already sunny smiley.

Far above, we hear something more. The silent tremor of radio waves exploring, extracting, and expressing data to waiting moguls. Battered and scratched, the sign for independence turns off just ahead.

On our way home, metal starkness stares at soft pink lullaby.

-

Marion Union Station

Cache Owner hankpixie, only four years ago, dangles the delight of a train station. The whistle is calling, and we must go.

Our geomap travels north on Route 23, where nodding grasses ponder the trade-in of five acres for lucrative return on wealth.

Trees dressed for winter escort us toward Marion. Safe for now in their narrow cages, they remind that, should they go, life will be a barren field of blacktop, blanketed with speeding metal.

Quite by accident, we are drawn into the Huber Machinery Museum, where 150 years of creative invention follow the rainbow from horse-drawn plow to NASA rocket.

Coming from a creative family, Edward Huber arrives in Marion from Indiana and sets up shop, building new and improved farm wagons, and then inventing an inspired twist on the hay rake. He sells 200,000 rakes, for $5 each.

Patents spring from the minds and hands of new Americans as prolifically as wheat and corn from the rich, black soil. Still limited to only Natural Intelligence, inventors learn, improve, and innovate.

Our guide points out the Huber Hay Rake, as simple and complex as the first flip-phone. A Huber great-grandson walks through the museum, getting floors ready to wax. Pride in roots, in place, in achievement glows from the tractors, corn huskers, and threshers around us.

By 1894, Edward’s production has outgrown the barn floor. The name Huber, making the Top Ten as a German surname, derives from “land owner.” As immigrants begin to experience the power of individual ownership, determination, and belief, their communities stumble and rise again, building the muscles of self-governing toddlerhood. Edward becomes president of the bank, the light company, the savings and loan, the opera, and the library. Power shovels for coal mining, malleable iron, tile, brick, milling, and grain join his portfolio. Like all successful businessmen, he faces the happy yet unsettling question, “How much is enough?”

In 1964, less than a hundred birthdays after the hay rake, Marion Power Shovel engineers design and build a six million pound Crawler-Transporter to move Apollo and Saturn Rockets along the first mile of their journey of 230,000 miles. Ohio neighbor Wapakoneta sends Neil to the top of Apollo 11, where he chills on the Marion crawler.

Outside the museum, one 2,000 pound shoe of the Crawler has returned home, dwarfed by Great-Grandpa steam shovel, reminding it where the inspiration for the shoe came from.

We follow Edward’s footsteps around the corner to the Marion Union Station, where he leads the charge on installing the railroad. Our proud Cache Owner reminds us that a Marion native, Mr. Harding, got the station upgraded, and then ran for President. The trains brought celebrities and common citizens to Marion to hear him speak on his bid for the White House. Only two years later, this station received his funeral procession.

With the speed of clacking wheels on track, American fields are embroidered with steel threads, by business investors skilled in selling stock, raising money, and cultivating oil, steel, and railroad connections. Right on schedule, trains carry thousands of WWII draftees across the country, through this station. Like the Apollo rocket, a human mind still controls and directs these tons of careening steel. From the side window of the train springs a sudden happy message.

Within minutes, four trains have surrounded us, moving in different directions. Each sings the song of the railway, a whistle far in the distance, a rattle, clap, clap, and then two long, one short, and one long, the universal lullaby of the engineer.

We didn’t know our shopping orders were filling up so many train cars. Hay rakes and threshers give way to Kindles, Ring cameras, and Alexas.

With so much going on at geo-zero, our coordinates are unclear about our next move. As if on cue, our hard-working muggles serendipitously pack up.

Admiring today’s Bobcat iteration of Edward’s shovel and tread shoe, we begin the search. In March of 2020, a cacher logs the joy of having a treasure to hunt, a reason to get the family outside, and an escape from pandemic house arrest. Cache Nation echoes the gratitude through a long, long year.

True to the creative minds that have inspired us today, the cache hides under a model railroader’s version of a rock.

In 1971, The City of New Orleans took us for a ride, wondering if trains would disappear like flatboats, steam ships, canal boats and horse-drawn carriages . . .

And the sons of Pullman porters

And the sons of engineers

Ride their fathers’ magic carpets made of steel . . .

And the steel rails still ain’t heard the news . . .

This train’s got the disappearing railroad blues.No, they ain’t. They still ain’t heard the news.

-

Cascading Findings

In 2014, Cache Owner Nye-St-Mafia let loose a challenge with an avalanche of discoveries. We will find them.

On a bright, happy, wintry day meant for seeking out treasures, we follow the geo-voice north.

Mom Wilson’s Country Sausage shares the pasture with its tall, wiry neighbor. A third-generation business walks the tightrope of passing heritage on in the new frontier of screen-defined reality.

Our geotour lands an hour north, and 80 years back. In 1942, Marion residents looked out the window and saw the same tsunami of a rapidly changing world. US Army engineers displaced owners from 640 acres of land to build a supply depot, transporting food and munitions on the chessboard of World War II.

In 1989, the land sold for 1.1 million, and was renovated into the Marion Industrial Center. It is now a distribution, storage and manufacturing complex employing 1,000 people, who make things used by peace, not war.

German POWs captured in Africa came to live on this soil, in Camp Marion, from 1944-46. They cooked, cleaned, and did construction and farming labor for 89 cents a day. While they played soccer, or painted, or made jewelry boxes, thoughts of war drifted away like butterflies.

Down the road, a war munitions factory commandeered 13,000 acres from 126 farmers, by right of eminent domain. The Scioto Ordnance Plant Site gave the farmers two months to vacate, with below-market compensation for prime farm land. US Rubber, Atlas Powder, Kaiser Corporation and other manufacturing interests seized the moment. Pawns fell off the board.

After a year, the bomb and shell factory was closed due to overproduction. Now an airport and housing development sit where bombs were made for far-away lands. 1,100 acres returned to farmland, where they study war no more.

We turn the corner into the winter slush of manufacturing along Cascade Drive. Inventors and assemblers collaborate to keep the world patched together.

Limbs meet limbs, and proper introductions are made.

We leave our calling card.

The cascade of war is not finished with us. As B.C. turned to A.D., Persia, Greece, and Rome fought their way around the Mediterranean in pursuit of trade, materials, and labor. Powerful business owners captured ever more wealth and land. Small family farms and businesses slowly died, along with local cultures and art.

By the time the first millennium reached its one thousandth year, new kids on the block had moved in. Goths, Franks, Anglo-Saxons, Vandals, and Arabs flowed into Europe. At this critical moment, a movement for combining states in one great nation might have emerged, but it did not. Charlemagne, Alfred, the Gauls, and the Catholic Church gathered land into separate and warring nation-states. Life became one chess game after another, as kings and warriors fought endlessly.

When the printing press went viral, and Columbus landed not-in-India, European farmers, weary of war, lined up for a new life in America, in search of freedom to determine their own destiny and personal beliefs.

Happy to carry their wars into newly discovered continents, powers in the Old World fought for another two centuries, greedy for rights to the gold mine of colonial raw materials. When Napoleon redrew the map of Europe in the early 1800s, no one knew that 100 years later, war would cover the world.

As German Kaisers moved the next chess pieces on the board, pawns from across the sea fell into the crossfire. In 1910, more than 32 million Americans were first or second generation immigrants from Europe. They lined up to return to that homeland and fight the old country for the new. Twenty years later, children of those Americans found they had not yet escaped from the appetite for war in the Old World. The roll call echoes names upon names, when towns and homes were emptied, leaving only the silence of voices stilled.

-

Mini Dog

Ten years ago, Cache Owner Djdolle-and-donde lost their little dog. We will join the search.

As shimmering, icy air invigorates sleepy skin, the city weaves its tapestry of builders, fixers, cleaners, inventors, sellers, buyers, recorders, enforcers, and cheerful license plates.

Our geomap detours east, where the Olentangy River, running beside Route 23, takes a wide bend around Mingo Park.

Here the names Delaware, Mingo, and Olentangy hold long shadows of memory. As Pennsylvania farmers pushed tribal nations westward, the rich hunting grounds of Ohio country beckoned. Shale from the Olentangy River proved to be excellent for black paint and sharp enough for tools. Two hundred years later, a thirsty population depends on the river for daily water. A far-flung school system echoes the Olentangy name across 5,000 students.

Today’s gifts from this river are as unexpected as sudden tears.

Caught in a rising rush of icy water, tangled shoreline stubble transforms into jeweled royalty, robed like not even Solomon.

Spiraled and smooth, design and materials echo the precision of planets circling far, far above. In wonder and silence, we witness the mystery.

With miles to go before we sleep, we reluctantly turn away. The memory file moves to the brain’s beauty drive. Coordinates direct us to Marion, our neighbor to the north.

With miles to go before we sleep, we reluctantly turn away. The memory file moves to the brain’s beauty drive. Coordinates direct us to Marion, our neighbor to the north.

A historical marker speaks. As WWI ended and the prosperity of the 1920s kicked in, country graveyards gave way to burial within city limits. The business of death and final places of rest captures the attention of energetic entrepreneurs for the next century.

When we enter our final parking lot, it spills the tale of the snow cycle in Ohio. Silent flakes blanketing every branch with finest detail have given way to slippery road adventures, ending with piles of plowed and defeated grayness. We’re not unhappy to be in the gray stage.

When we enter our final parking lot, it spills the tale of the snow cycle in Ohio. Silent flakes blanketing every branch with finest detail have given way to slippery road adventures, ending with piles of plowed and defeated grayness. We’re not unhappy to be in the gray stage.

Previous finders have pondered at length a set of four traffic lights at our geo-zero. Is it a ghost town or future development? Or perhaps a generous effort to make sure we can all get to the cache without any unnecessary accidents? In 2016, lack of attention threatens our little puppy with the dreaded archive. New Cache Owner Jaybirdchauffer generously steps up and takes in a foster pet.

The log is wet, the pen won’t write. Should we say we couldn’t sign? Not this team. We make it work.

The blank fields stare back at us, shadowed by houses peeping and creeping across the way, waiting for the sidewalk to walk on. Road laps hungrily at soil, trees write their wills, but for today, we stand with Mr. Silverstein, where the sidewalk still ends.

There is a place where the sidewalk ends

And before the street begins

And there the grass grows soft and white,

And there the sun burns crimson bright

And there the moon-bird rests from his flight

To cool in the peppermint wind.

For the children, they mark, and the children, they know

The place where the sidewalk ends. -

Could it be blue

Cache Owner sunflowersu, in 2017, places a cache, which, in a star-studded galaxy of caches, through no fault of its own, becomes truly unique.

We are driving out of Mohican country for the last time, hearts still held by healing trees, where fields and floods, rocks, hills and plains repeat the sounding joy, repeat the sounding joy, repeat, repeat, repeat the sounding joy.

As night falls, the geomap points toward Loudonville, where the Black Fork, Clear Fork, and Lake Fork merge into the mighty Mohican. Campgrounds and canoe liveries abound, offering the outdoor life of ancestors on land and water.

The Mohican Country Market rides the wave of vacationers each summer. Like Hocking Hills, with its 267,000 waterfall postings on Instagram, the Mohican Valley is on the map of investors in hot pursuit of tourism dollars.

Our pursuit lands us in the parking lot. For five years, a logged conversation has followed could it be blue . . . around this parking lot. As the market owner rearranges furniture, the cache moves along. Loggers demand fixed coordinates. The long-suffering CO consoles and comforts, reassuring them that they will find . . . ol’ Blue, wherever Blue may be today.

Hello, Blue. We found you.

Whose car just started? It sounds like ours. Is someone stealing our car? Where’s your remote? You just remotely started the car. How bout getting off that chair?

Westward bound on Route 39, small towns slide by the windows, doing what small towns do.

Darkness deepens over the hillsides, houses shelter the homes inside, our number points the way home.

City spins into focus, with thought of familiar rooms, beloved faces, and soup warming on the stove.

Against the press of lights blaze, tires rumble, rush of exhaust, in silence, trees and grass still rise.

-

Mario’s Playground

In 2016, Mario took Cache Owner lilguns for a walk, and buried a bone for us to dig up. Bring a shovel.

The journey speeds north, lackadaisical winter traffic as sleepy as the gray-blue skies. Cell towers march along the interstate, trading location pings for seamless internet fellowship.

As we turn east, skies clear. Finally we stand on the 113-foot tall dam, filled with earth, holding the waters of Pleasant Hill Lake. The Great Flood of 1913 left over 400 people dead, with a bottom line loss of $73 million, at a time when a brand new Sears Roebuck sewing machine with stand cost $10.45, and a Winchester rifle cost $12.50.

In a galactic effort, engineer designers constructed 16 reservoirs or dams over 8,000 square miles, changing many backyard views from a town to a lake. As the state came together in the aftermath of 1913, Buckeyes relocated, changed roads and driving habits, paid for the whole plan, and, in the floods of 2005, saw 7 of the 16 dams reach flood level. All seven held the water back.

Our trail continues along water now cool, peaceful, and serene. Shaggy evergreens flaunt avocado shades. Bare-branched neighbors mourn at their own fashion funeral.

Mario is a hiker dog. Moss and matted leaves, mischievously disheveled, mimic Michael Jackson’s moonwalk on a vertical climb.

Pancakes of rock layers greet us at the top. Completely silent, their solid strength calms, intrigues, and at last reveals a tiny mouse in this mythical elephant.

But this geotour is not done with us. The iconic Mohican Covered Bridge beckons to new heights.

Eighty feet tall, the Mohican fire tower will give us a step to climb for each of its 100 years, where it has stood through war, flood, drought, moon walks, 15 Presidents, and its own debut as a social media photo shoot.

On Step 75, the buds of Spring surprise, with soft, tentative baby fingers, still braced for impending blasts of Arctic snow, hunkered down in confident courage.

Another flight of steps, and the hills of Mohican ripple in a dance both moving and still. Sky touches earth in flaming sun strands. Clear, cold air silences all sound.

We will descend, and crawl along the road far below, as beetles on a dusty crack. Beetles who can lift ourselves 80 feet into the air, gaze in awe at majestic magnificence, feel the soul stretch to infinity and eternity, and climb back down without breaking a leg.

Trees find us as we resume beetle status, gently reproving. This winding road is not for beetles, but for those who can build fire towers, design dams, share a tiny mouse hidden in an elephant, and care in all ways for life on this planet.

-

Dark Treasure

Like most seven-year-olds, the log for Cache Owner now-we-are-nine loudly voices its opinion. We will be sure to add ours.

We return to Pleasant Hill Lake, a 70-year-old with 783 acres of outdoor playground, sitting in the laps of both Ashland and Richland counties. Like all reservoirs created to avoid another Great Flood of 1913, Pleasant Hill brings lake life within the reach of thousands of Ohioans.

As evening shadows lengthen, the online logs wheeze and whine like an old accordion. This is a dangerous trek, across a gully, it’s 300 feet off the coordinates, contents of the cache are strewn around the ground, it took ten of us to find it. Yes, yes, and yes. And will we have to call eight friends?

The CO remains silent. As unique as snowflakes, some cache owners visit often, refresh paper and baggy, add comments to the weblog, assure that all is well, admonish that only actual signers can be logged, or reset the coordinates. Other owners plant the cache, then . . . say nothing at all.

And so, in this case, we find that all those who wander. Are. Definitely. Lost.

The lake offers sympathetic silence. Waters flow in from the Clear Fork, and leave to join the Black Fork of the Mohican at Loudonville. If you need directions to the Ohio, keep paddling your canoe thirty miles south, as the river winds, to where the Mohican joins the Kokosing, rebranding as the Walhonding, then turn east twenty miles where you will join the Tuscarawas as it becomes the Muskingum. Turn south and paddle for 80 miles, and that river in front of you is the Ohio. Tribal names still echo those long-departed canoe-drivers, guided by communal memory and their unscreened, nondigitized Local Landmark System.

Tiny bi-valves add their clammy comments to our mysteriously dark treasure hunt.

With a smile both shy and stunning, this little jewel finds us.

For two years, cachers try to work out the coordinates. Finally in 2017, N40 38.356 and W082 19.835 stick. For the next five years, and counting, logs will regularly pass the baton forward by referring to the 2017 coords.

Bark scrapes hands, twigs puncture knees, leaves hurl feet downward, burrs glue shoestrings, every sense sings, as we wander homeward.

Skip to content