-

E I E I O 2.0

In 2017, Cache Owner Charlie Hunters turns up the volume on Old Macdonald’s Farm. True bliss for a six-year-old playing hide-and-seek.

Heading north, our geo-map directs us to Stratford Ecological Center, just south of Delaware. The parking lot is already buzzing with muggles, big and small.

Left with 236 acres of land when her grandfather suddenly falls ill, Gale Warner’s burning desire is to create a farm and nature sanctuary. Her first hire is an agricultural student. We think Old Macdonald would approve.

Interns, volunteers, staff, and a new executive director join the farmer over the next 33 years to create the sounds of clucking, mooing, baaing, and crowing, now calling us. The guards scrutinize the latest intruders from their perches in the tree.

A rush of warmth and spring’s lush early risers greet us as we roll open the greenhouse door. A chorus of kale, spinach, broccoli, celery, cilantro, cabbage, and even miner’s lettuce, a staple for those brave souls long ago, sings forth every shade of green imaginable.

The farm’s newest member is excited for company, not yet aware that chickens rule. The pecking order requires a strict examination and admittance policy.

Conferring among themselves, the guards come down to meet us, still carrying that skeptical look.

The successful births of over 20 lambs this spring gives testament to the farmer’s unending dedication and commitment to the support of sustainable agriculture. Over the past several years, he receives two awards for his outstanding care and performance.

15-year-old Rafiki holds the story of a past visit from the governor and other persons of some importance. Today the sentinel still stands. Who else is going to keep these innocent faces in line?

The goats have settled down for their second chew and our cache is calling. We head for the woods, leaving the inviting warmth and companionship of Four-leggeds and sweet-smelling hay behind.

If all goes well, we will be returning shortly. . . just watch for mud…flooding…dive-bombing birds…oh and hopefully no quicksand. . .

One last on-looker bids us farewell, or is that a smirk . . .

An unexpected treasure bursts into color before our eyes as we strike out on the well-worn geo-trail. A hidden hill blanketed with emerald green whispers softly in the breeze, showcasing wonder for the adventurous, wandering soul.

Tiptoeing out of their winter cocoons, each bud contains a power house ready to unfurl into a pulsing leaf, collecting sunlight and energy for a waiting planet.

A heart-shaped opening ahead beckons, over twisted tales of forest tumult. From the unknown and unsung locations of our Cache Nation hero-owners comes a message of fun and fellowship.

The CO shares this treasured spot as the mishap of his first geocaching adventure, turning up empty handed but still undaunted. After seven years of experience in the field, he returns to install version 2.0, with hopes of sharing the joy with others. Now the cache passes to a new adopter and 3.0.

Our six-year-old is having a difficult childhood. The container has been cleaned, cracked, repaired, cracked again, and most recently encased in plastic with hopes of housing a dry log inside. Like the disheveled mayhem of leaves once brilliantly green, then orange, now tangled in a mass of new forest life, the geo-galaxy begins a new season of soul food.

the old and new

the brown and green

cachers with 10,000 finds and cachers with 12

footsteps left behind, watched by invisible creature eyes

logs left on the forest floor

in a woven internet of nondigital, nonpixelated, noncellular connectivity

-

Sages in the Orange Trunks 2.0

In 2017, Cache Owner Charlie Hunters hides a cache in a line of poetry. We go seeking sages . . . or oranges . . . or trunks.

In long ago memory, in northern Delaware County, stands the 1800’s village of Stratford, home to mill workers, a church, and a cemetery. Making his fortune as a judge and bank president, Hosea Williams acquires the mill just behind the “Old Stone Church” and cemetery. Six generations later, Gale Warner takes her grandfather’s 236 acres, surrounding the original mill site, and creates the Stratford Ecological Center.

After a lifetime of flying across the world as a peacemaker at Russian war tables, Gale returns to her inheritance, a tiny spot of land where she brings to life her ideals of social and personal empowerment.

Bringing peace to the earth and the Two-leggeds who walk upon it, Gale designs a microcosm of ecological balance, spread forth in a simple yet enticing environmental education/nature center.

Instead of hungry developers quilting an upscale golf course, Gale feeds an entire county with a patchwork of vernal ponds, woods, creeks, gardens, and Four-leggeds.

Today’s joy breaks forth and washes over us, in the fresh green buds, warble of birds, and whispering reeds of Gale’s dream come true.

Under the watchful eye of swooping tree swallows, we begin our quest. The nesting boxes provide shelter for young ones not yet born, while parents-to-be take advantage of the prairie to collect their allotted 2,000 insects for the day.

Continuing on our way, we follow the trails of creatures who call this woods home.

Grass turns to soil churned by spring storms. Two paths diverge . . . into a muddy wood . . . or back to civilization. And we, we took the one . . . .

Well, we’re geocaching–what did you expect the answer would be?!

For 33 years, since the ODNR established 95 acres of Stratford as the Stratford Woods State Nature Preserve, fresh spring rains have watered the ground beneath our feet. This time maybe a little bit too much.

Today would have been a great day at the mill as the stream churns and foams beneath us. Keeping our eyes on the prize, we cross the bridge without loss of life, limb, or camera.

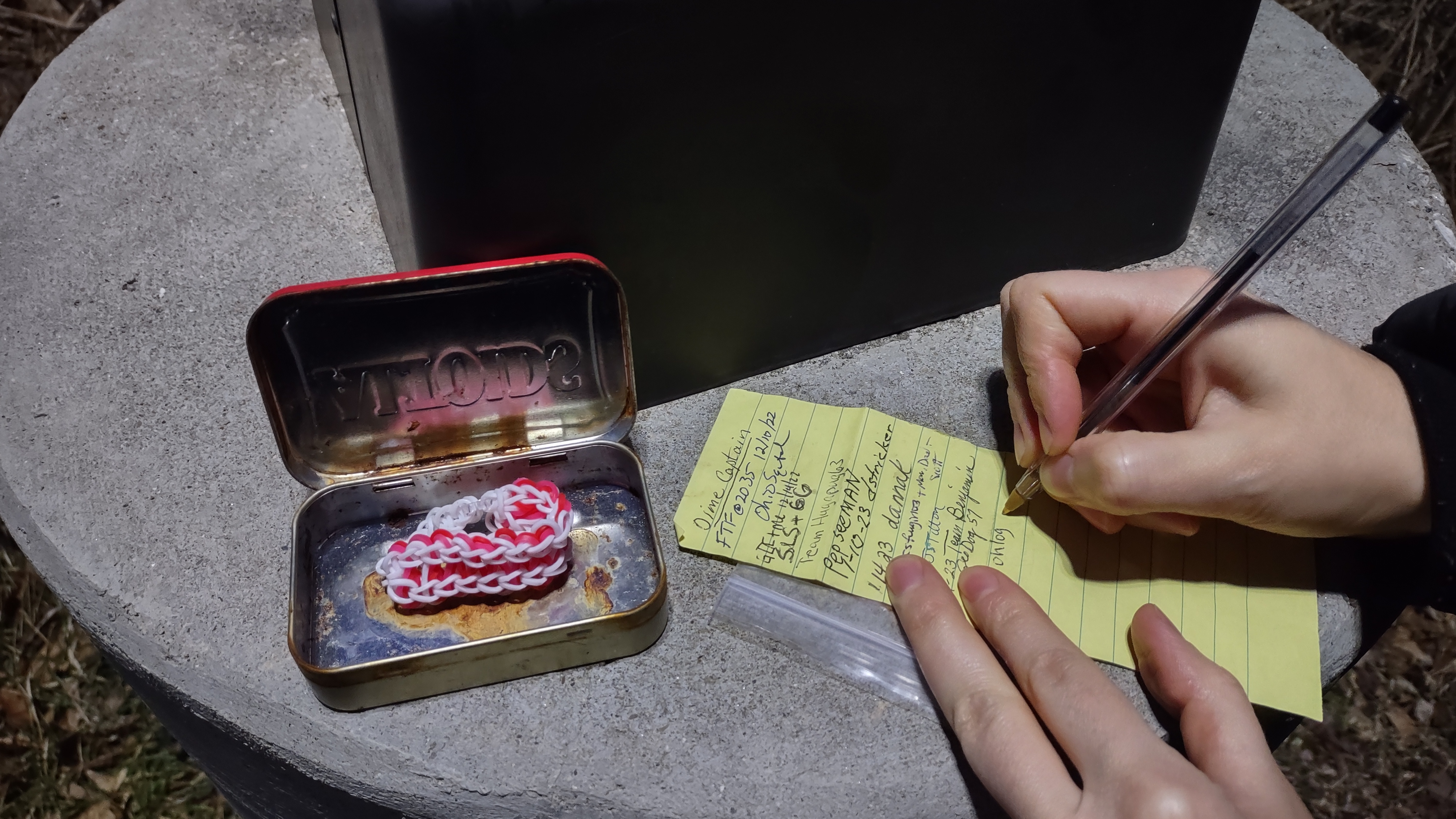

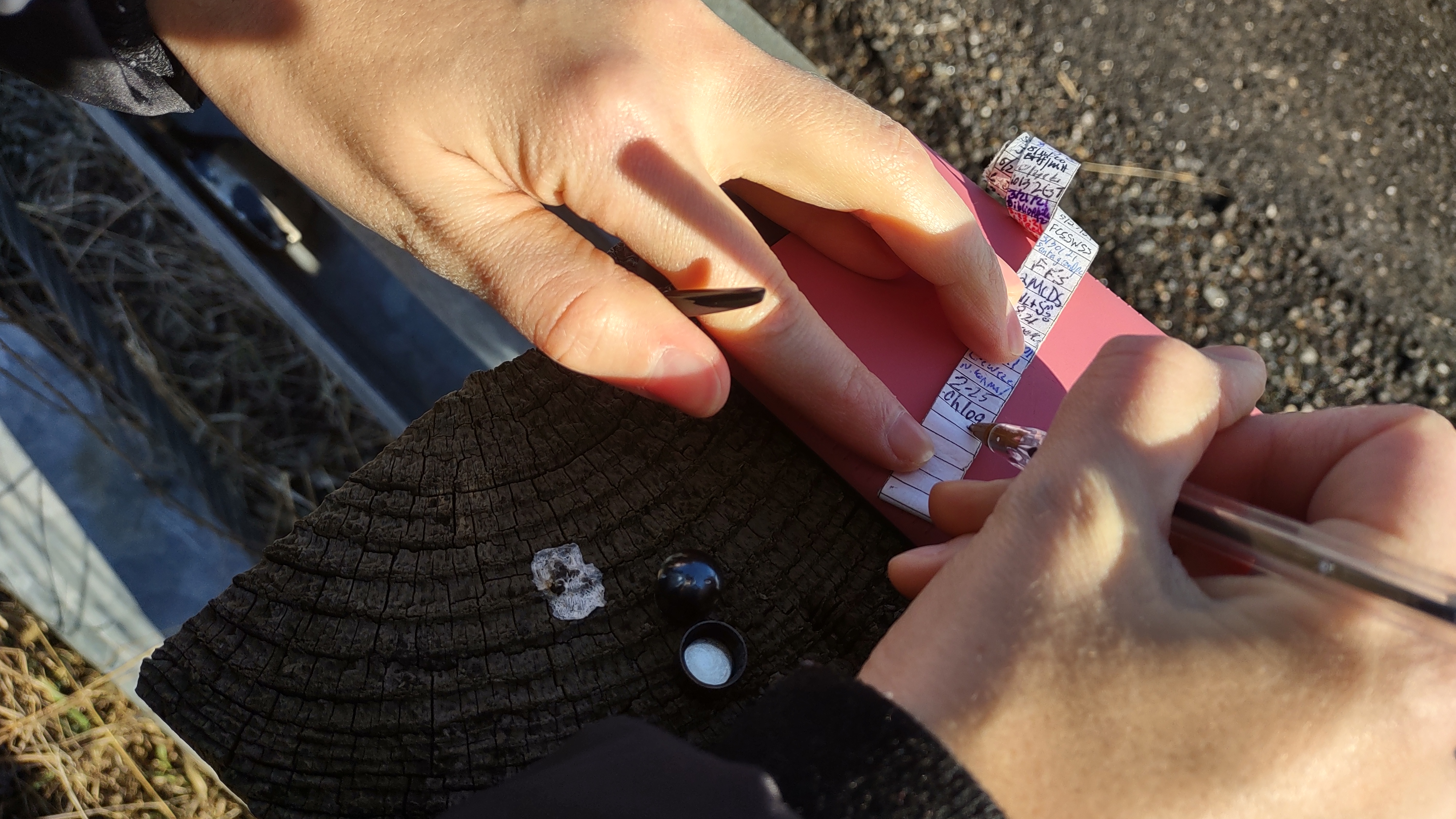

As a final challenge, we crest the top of the hill to find Stratford’s Historic Cemetery sprawled out before us. We stand on the same ground as 1812 war veteran Colonel Forrest Meeker and his wife Patience. In 1816, they say goodbye to their darling six-year-old, laid to rest as the cemetery’s first resident. In the background, a careful mathematician realizes Capt. Kooken could not have fought in the Revolutionary War . . . and makes the correction, 2023 style.

Here the CO pays tribute to the sages who lived . . . and died young . . . on the Ohio frontier. Two centuries later, war over this land has ceased. Visitors come and go, adding their respects.

The hidey-hole is perfect. Now in its third life of ownership, the cache adopts a new human.

As the silent forest leaves us behind, spatters of spring arch over the tumbling, boisterous roller coaster below, on its journey toward waterfalls, and those who search them out in this Season of Singing Streams.

Down the road, the Old Stone Church chooses a new owner. The architect, who spent three years adding ductwork, electrical lines, plumbing, drywall, floors, ceiling and insulation, comes to mow the lawn around his office. Deep roots stretching upward through generations bring the work of joy, creation, fellowship, service, and passion to this spot once again.

-

Dime Captain

Cache Owner captphil commissions a new officer in 12/2022, under the direct command of Dollar General. We are ready for a five-star tour.

On our final journey to points north, airplanes have started today’s game of Tic-Tac-Toe across a cerulean Etch-a-Sketch. Wiry godzillas collect detailed agronomic data from those who shepherd this soil, pushing carbon payment programs that will slowly edge out family-scale farms.

Our geodetour takes us to the heart of Mansfield for the last time. In 1888, Frank Black returns to his hometown. He is young and ready to work. With his Irish immigrant father, he opens a brass foundry. They flounder wildly in the panic of 1893, until a New England engineer, who knows how to run a business, moves west.

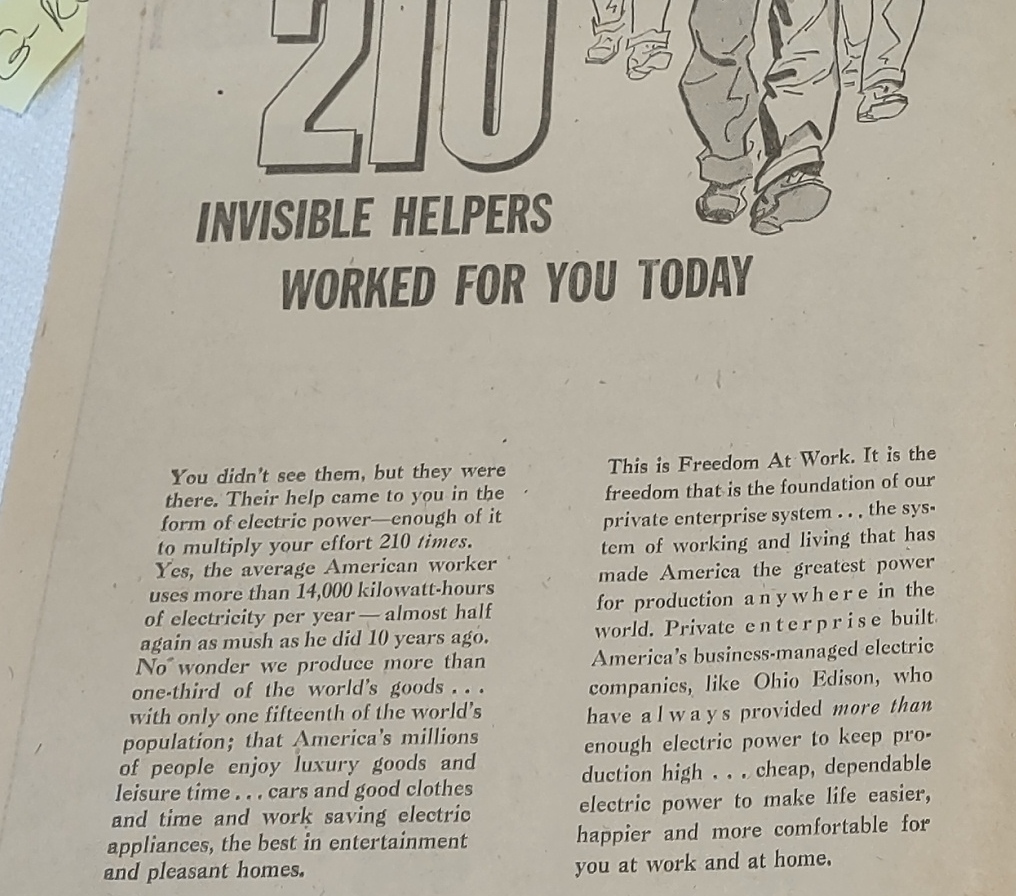

Over the next 30 years, 290 pages of catalogue and 1,100 Ohio Brass craftsmen will spread trolley cars across the nation. When Frank Black becomes president of OB in 1902, Engineer Charles follows as Vice President. Together they create electrical systems, using words like high tension, voltage transmission, and high capacity, to carry power to the whole nation, and from there, a massive power grid around the world.

Pride in workmanship, sound design, targeted sales, fairness, honesty, and skilled administration write the book for 21st century MBA programs.

In 1928, Charles, now Ohio Brass President, watches Kingwood Hall rise from Mansfield soil. He envisions a grand French châteaux, where music, dancing, flowers, and fine food will entertain European businessmen shopping for brass.

Tall chimneys, steep roofs, and curving walls deliver. Courtly beeches suitably frame a mansion meant to impress.

Fine china, mahogany furniture, devoted domestic staff,

hand-painted wallpaper, Waterford Crystal chandeliers, silver tea sets, bathrooms for each bedroom,

a home office with fresh-cut flowers, two rooms full of books, and tables with French glass legs frame Charles as a billionaire boy of his time and place.

Married first to a board member’s daughter, Charles goes through two divorces, both without children. Partying with young females becomes a public scandal.

When Charles dies in 1952, his will leaves Kingwood to the people of Mansfield. In 1953, it opens as a non-profit educational institution for horticulture and other community enrichment activities.

Today’s volunteers staff the house, work in gardens, host special events, and keep all things green alive in the heart of Mansfield.

Silent staff quarters, butler’s pantry and kitchen echo with whispers of the companies that grew up and moved out of Mansfield, and the brilliant minds behind them.

Kingwood greenhouses blush with color and beauty all year long, inspiring today’s urban gardeners to sprout new ways of bringing nature to the city.

Reluctantly we step from a very fun gift shop, back into quickly falling darkness. Our geotrail turns south from Mansfield, down Route 42, and east toward Clear Fork Reservoir.

Just above the lake, the Ohio Bird Sanctuary tweets an invitation. Blaze the peregrine falcon has a story to tell.

Presiding over this benevolent bird hospital, Mr. Blue Jay happily hosts nature camps and school programs. As long as you bring mealworms.

Even the cedar waxwing isn’t shy. Everyone is on board with helping families enjoy a three-dimensional, fresh air, unscripted reality.

Back on the road, we make our way around the lake. This week’s Saturday night date is cozy, cosmic, and cost-friendly.

Southwest of the reservoir, lemony yellow tells us the General has arrived.

Rations are looking good, and hungry troops are checking it out. Just turning 85 years old, a family-owned business, started by a high school dropout with $10,000, now operates 16,000 stores.

But the General orders us outside. Our Dime Captain is on duty, manning the light post.

Leaving a taffy bracelet for a captain who is still only three months old, we score our smiley.

Finding our way to the interstate, the world of unmarked blacktop and gravel crossroads fades into the rear-view mirror.

While Venus and Jupiter shine above, all around us glows a world of joy, daily work, camaraderie, the feel of the earth beneath one’s feet, the windows of home, and the bounty of hidden treasure.

-

Over the river and through the woods

In 2007, Cache Owner twobears102174 invites us to a feast at Grandmother’s house. Hooray for the pumpkin pie!

Stringing our copper thread through the northern needle, we stitch miles and miles together, huddled under the downy quilt of cotton-flecked batting far above.

The Clear Fork Reservoir exits at Lexington, just south of Mansfield, where OH-97 winds northeast. When the Clear Fork branch of the mighty Mohican sank under the reservoir in the 1940s, Mansfield filled up a glass with 4 billion gallons of drinking water.

Along the shoreline, enchanted by the sparkle of dancing light, wild weeds of winter wave and whisper.

The soft, rich clay of the Stoller Road trail rears up, reshaping soil into a sculptured mile of molasses and Gorilla glue.

Wild and free, old-timer leaves soak sun into gnarled bones.

A tiny beauty parlor puts finishing touches on today’s demanding stylistas, who gaze unspeakingly at an eerie finger beckoning us onward.

Colossal pines, intertwined with secrets of eons of winters and summers, anchor the water that so surprisingly arrived at their front door 75 years ago.

We are halfway there. Gulls cackle across the water, geese trumpet that they are the real heavy lifters here, and woodpeckers tap out Morse code jokes to distant relatives, about the Two-leggeds sliding through the mud.

A fallen forest monarch allows us to climb on. The June tornado took no prisoners as winds brought down decades of shelter for all tiny forest creatures. Even in death, the tree will offer up nourishment for the tiniest microbes in this circular biome.

Like wounded spiders, branches reach and balance on earth never before touched by these fingertips, forming air and light into a eulogy of loss.

The tiniest of babes awaken and stretch, sending roots into long ancestry of leaves, bark, and soil. Aunts and uncles tower high above, in a world of wonder and joy.

With an animated roster of nicknames in past logs, the Twin Towers emerge like Stonehenge. Here The Rich Doctor built his 1920s hunting lodge, where drinking, hunting, gambling, and carousing added technicolor to Mansfield legends. Rare guns, a very loud phonograph, and a favorite hunting dog round out the story.

One night the dog disappears. The dog groomer named Homer disappears. The hunting lodge burns down. Everything is gone. Except. The sound of baying and howling through the dark Clear Fork nights. And the sound of Midnight Rhapsody wafting down from the fireplace.

Past cachers record a fruitless DNF in 2014. They return again three years later, then at last, in 2020, on visit #3, they land the fish. Earnest geo-finders stand beside the cache and record their coordinates into the weblog. New searchers scroll through, looking for clues in past logs. They find that each coordinate pair leads to a different spot. The watching trees would ROFL if they could. As it is, their winks catch the drifting phone waves, twist them into pretzels, and mail them back down to the Two-leggeds.

In 2020, cacher BrotherTim offers advice for the ages . . . If you get yourself in the right position, this one will jump right out at you. Otherwise we’re gonna be walking in circles for a very long time.

Our sharpest-eyed team member climbs down and back up the ravine, looks across, and spots the cache. Pointlessly wandering, our searching team member listens to the shouted directions . . . and scores.

Along the mile backward, a forest hums to rest. Long shadows waft through loftiness of unseen branches, bursting toughness of bark, quivering leaves waiting for buds still wrapped in sleepy warmth.

With a gentle kiss on earth’s forehead, repeated each night, radiance reassures that all is well.

Across a rotating planet, never-ending sunsets compel earthlings to sit in stillness, sheltered for these brief seconds from the scuffle and struggle of Screenworld, mentally filing and logging

the blessings which hallow our days.

-

Think Inside the Box

In 2013, Cache Owner Faxon7 dons a disguise that already has us thinking outside the box.

Today’s young entrepreneurs pull up alongside. As the promise of a college degree fails to deliver, energetic upstarts skip that exit and head straight for business ownership.

With 43 miles to go, skies are looking like spilled milk, which seems to be drizzling down into gloomy traffic.

Our exit ramp spills into the brand new North Central Ohio Industrial Museum, which promises to tell us something about being American.

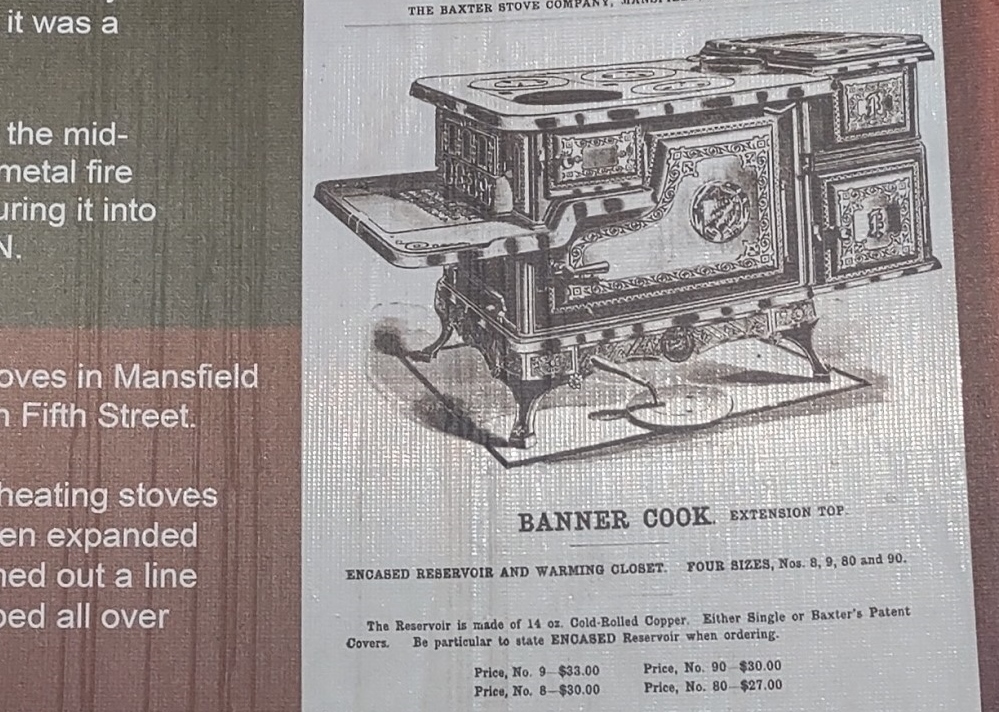

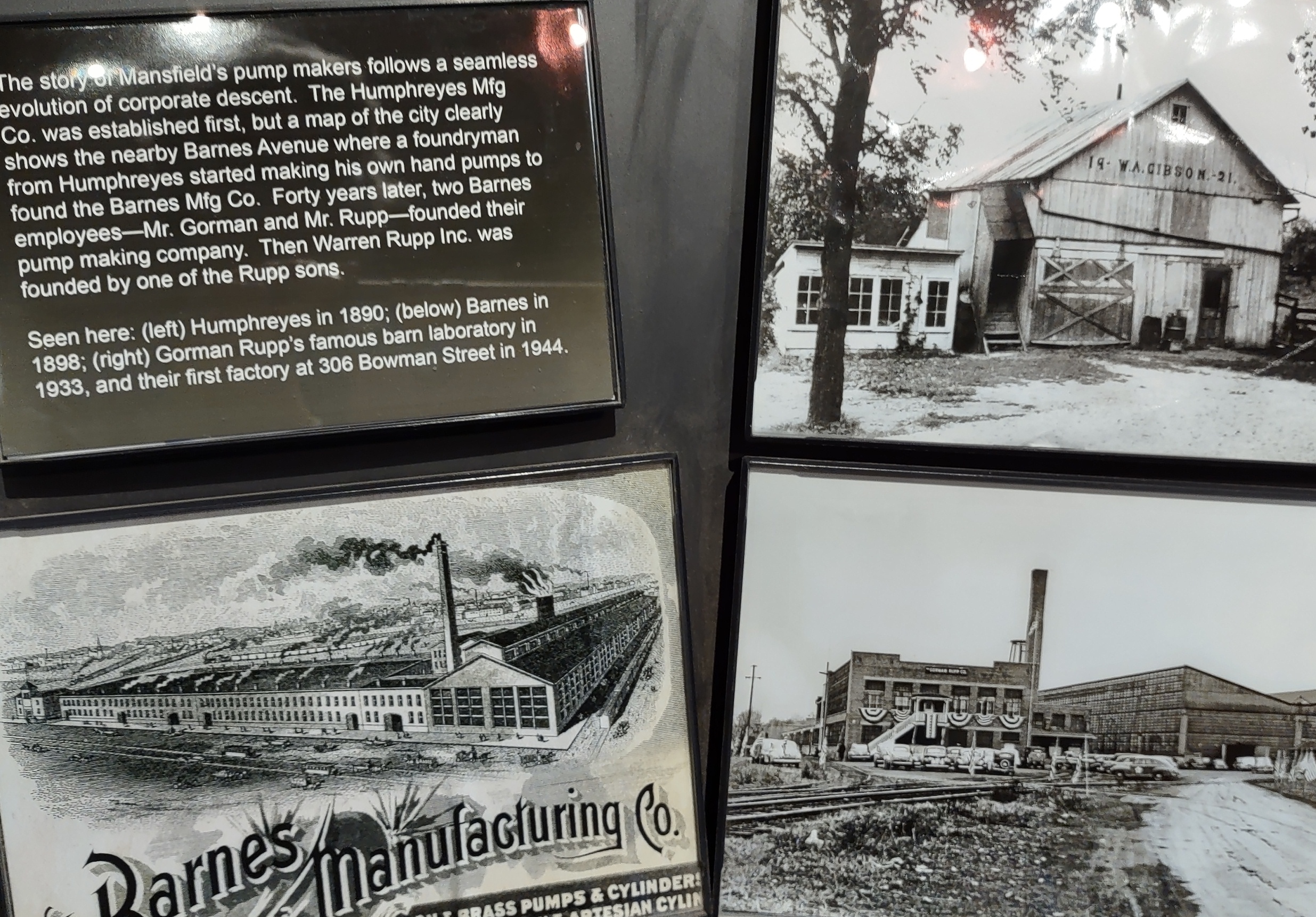

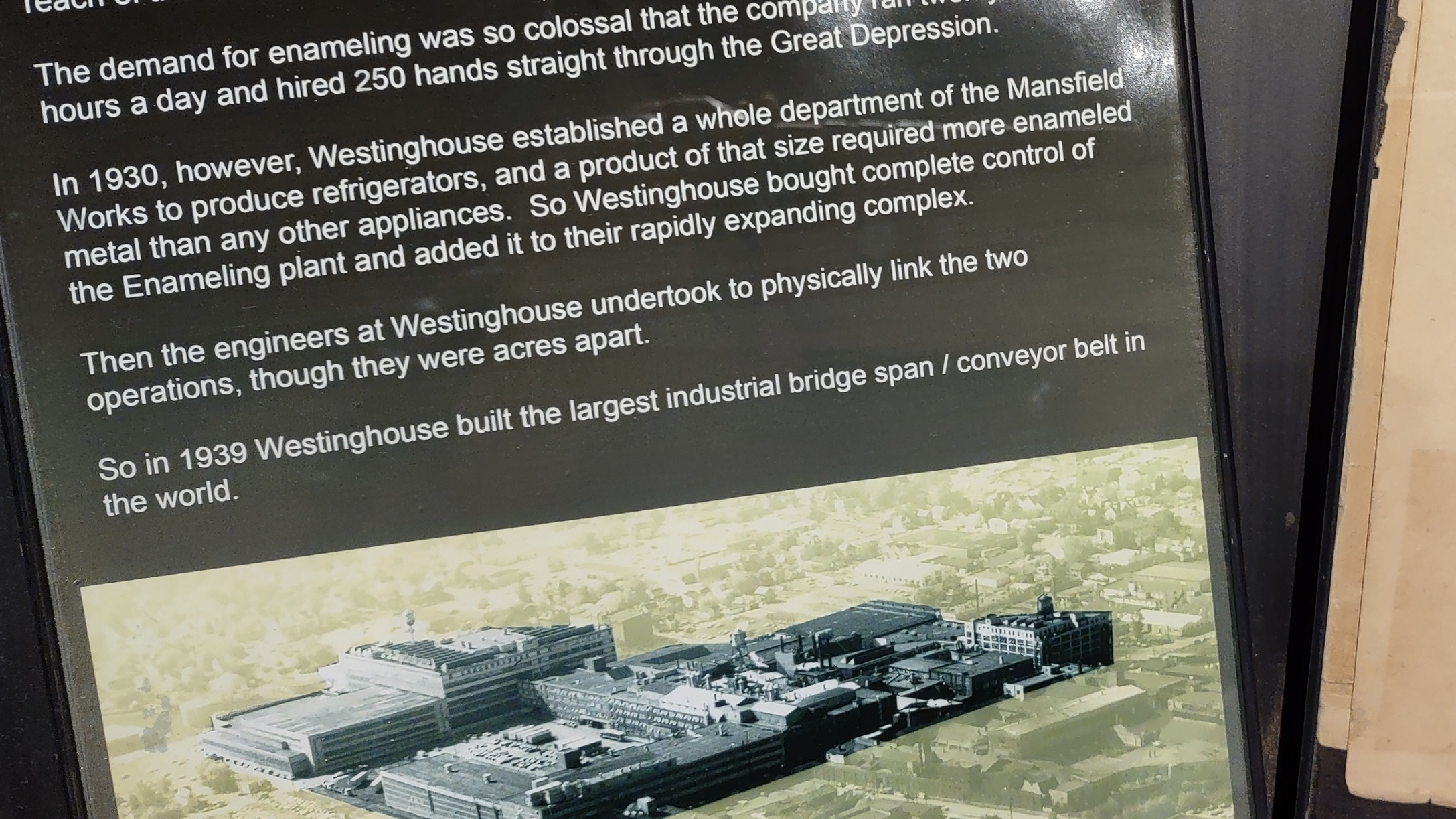

In 1883, the Baxters figure out how to make a better kitchen stove, first by casting iron into a mold, then by upgrading to electric power sources. Westinghouse sits up, takes notice, and moves to Mansfield. Across town, the Humphreyes, Barnes, Gormans and Rupps stay up late designing hand pumps, power pumps, and heavy duty industrial pumps. Coal flies from southern Ohio hills like startled starlings, racing along newly laid train tracks, and finally settling on foundries across the state. They are churning copper, brass, and iron into anything that will make life easier, faster, or cheaper, aka anything that will sell.

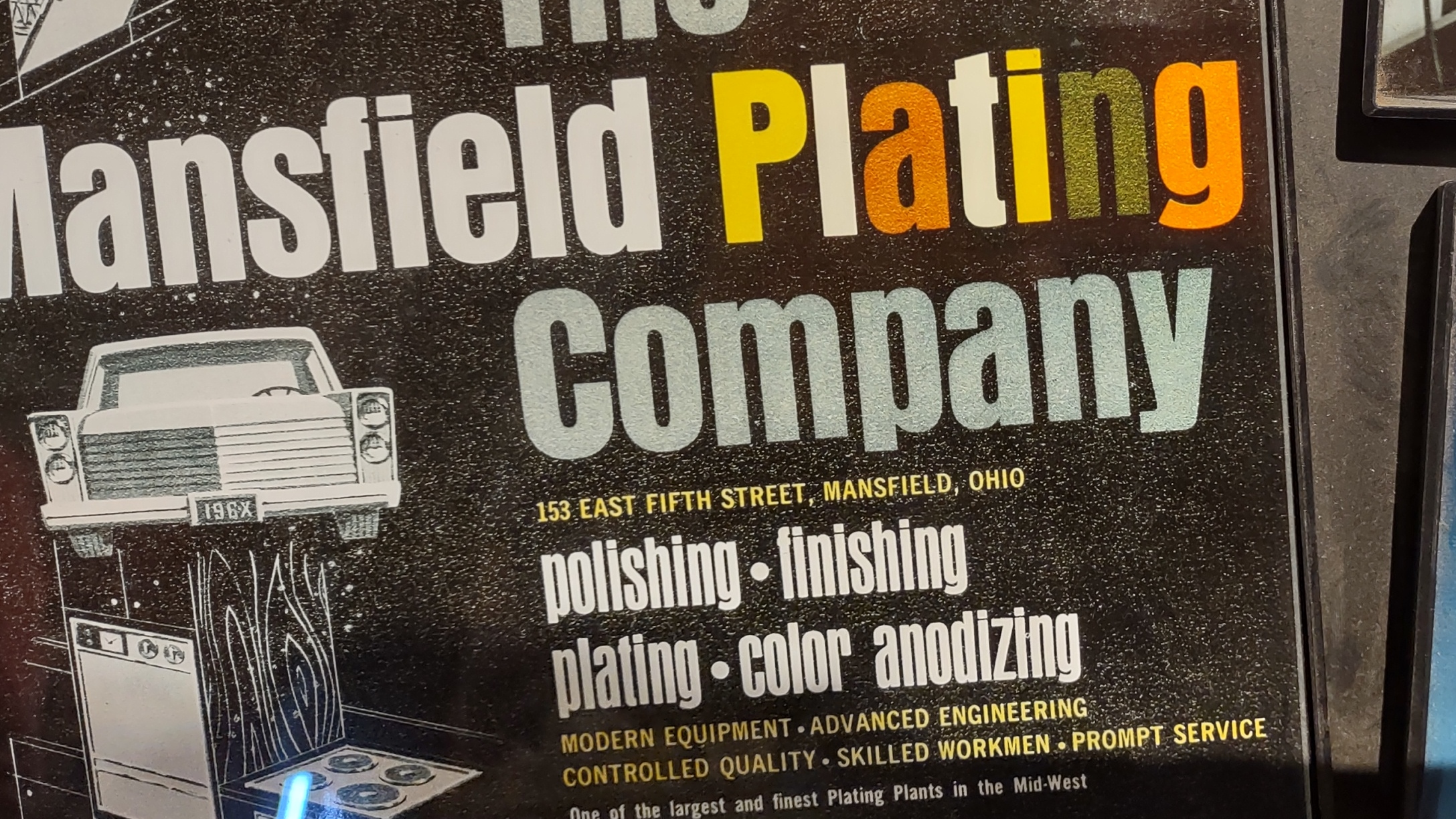

Forming a perfect hashtag, Mansfield railways connect eastern shipping ports, western farmers, a Great Lake, and slowly dying southern canals. Enamel plating companies coat newly invented appliances and cars, and ship them out. When plastic arrives as the new kid on the block, assembly lines click refresh. Equipment, design, labor, quality, and customer service define American innovation for the next century.

Something called corporate descent allows seasoned laborers to stash away mental blueprints from their present employer, save or gather capital, and then open up a similar business in a vacant building. Constant change driven by competition joins the color palette of American identity.

When the Baxter stove company burns to the ground in 1899, they rebuild. When the plant burns again in 1910, a new fireproof factory is built. It succumbs to bankruptcy in 1916. Westinghouse arrives at the party and needs an empty stove factory. American blood, seeming to thrive on disaster, finds a way.

Tappan upgrades from kitchen stove fire boxes [click] to electric stove thermostats [click] to microwaves. Dominion begins to sponsor TV shows with ads for waffle irons and popcorn poppers. Like ever new and marvelous social platforms unfolding across the screen, the fathomless possibilities of electricity surprise and enchant a consumer population.

Brass production immigrates from the Old Country, finding deep wells of copper and zinc across a fresh new land. By 1888, Ohio Brass is making all the buckles on the horse harnesses in town. When horses are chased out by street cars, OB makes the cars. OB engineers are ready when electrification arrives, inventing ways to move power safely through miles of transformers.

Left behind in the slow lane, trolleys get whiplash watching the brand new auto-mobile plunge by. From horse-drawn hours compacted to trolley-car minutes, Americans rocket forward into four-wheeler milliseconds. There’s so much more time to drive away to the next adventure, since gleaming appliances make food, wash clothes and dishes, sweep the floor, and keep groceries cold or hot. The tire factories of northeast Ohio make it all happen.

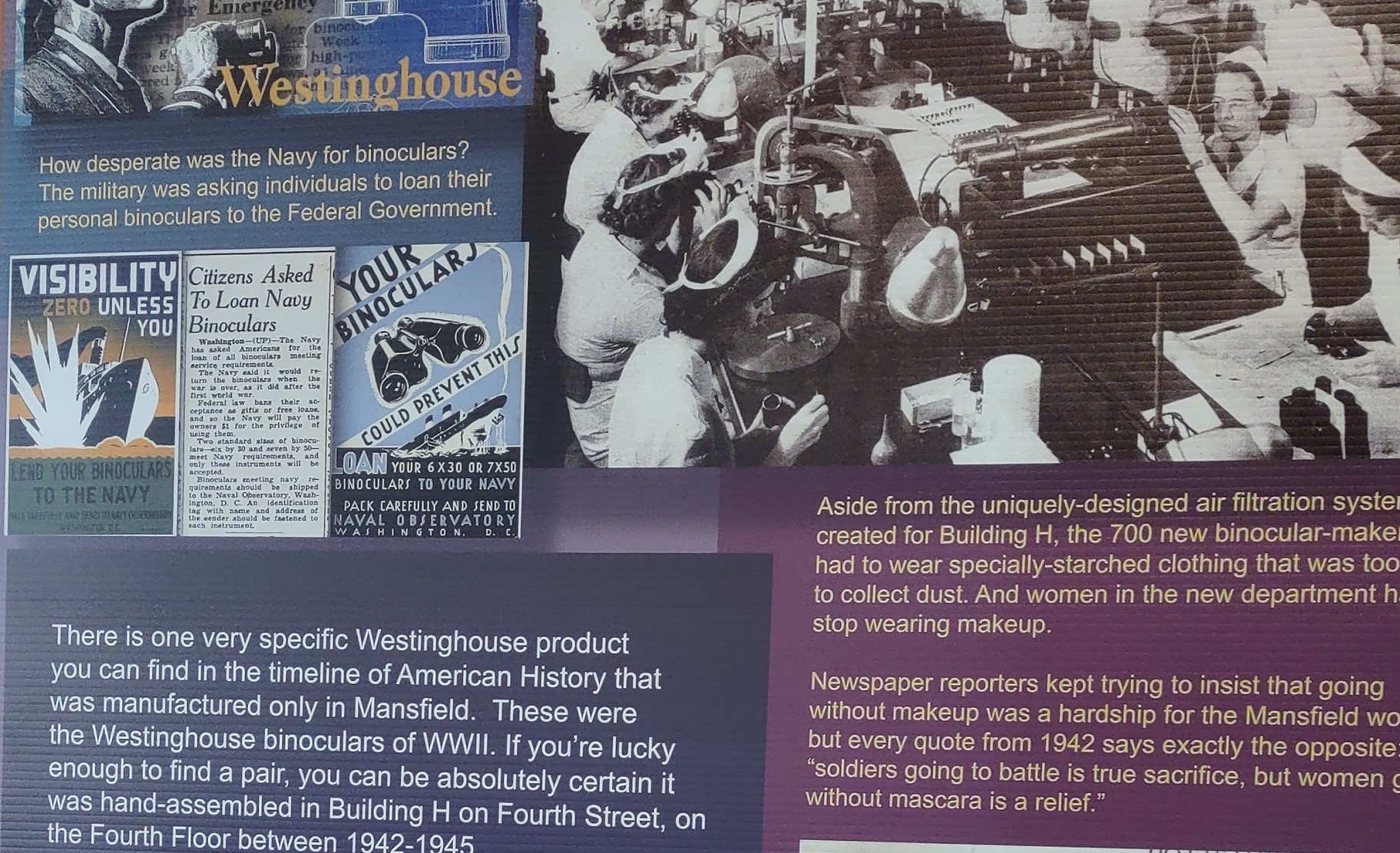

A burgeoning military, fueled by wars stretching across the globe, demands weapons, machinery, and tools of combat in a perfect figure eight of invention, production and tax money. Nine Mansfield companies are recognized by the military complex for pivoting to patriotism in action.

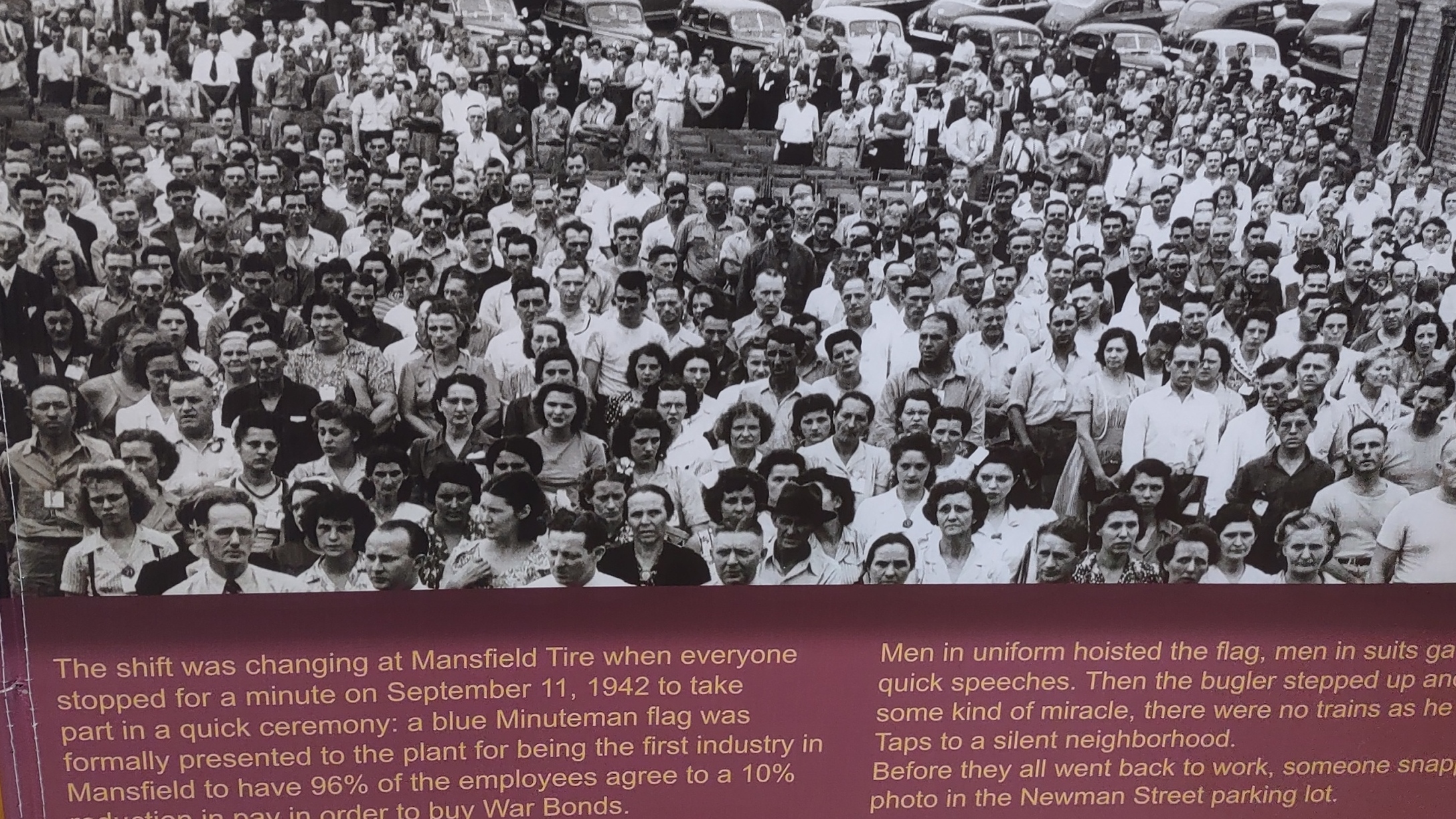

In 1942, Mansfield Tire employees are asked to take a 10% pay cut to buy War Bonds. They agree, and, to a silent audience, on 9/11/42, Taps is played.

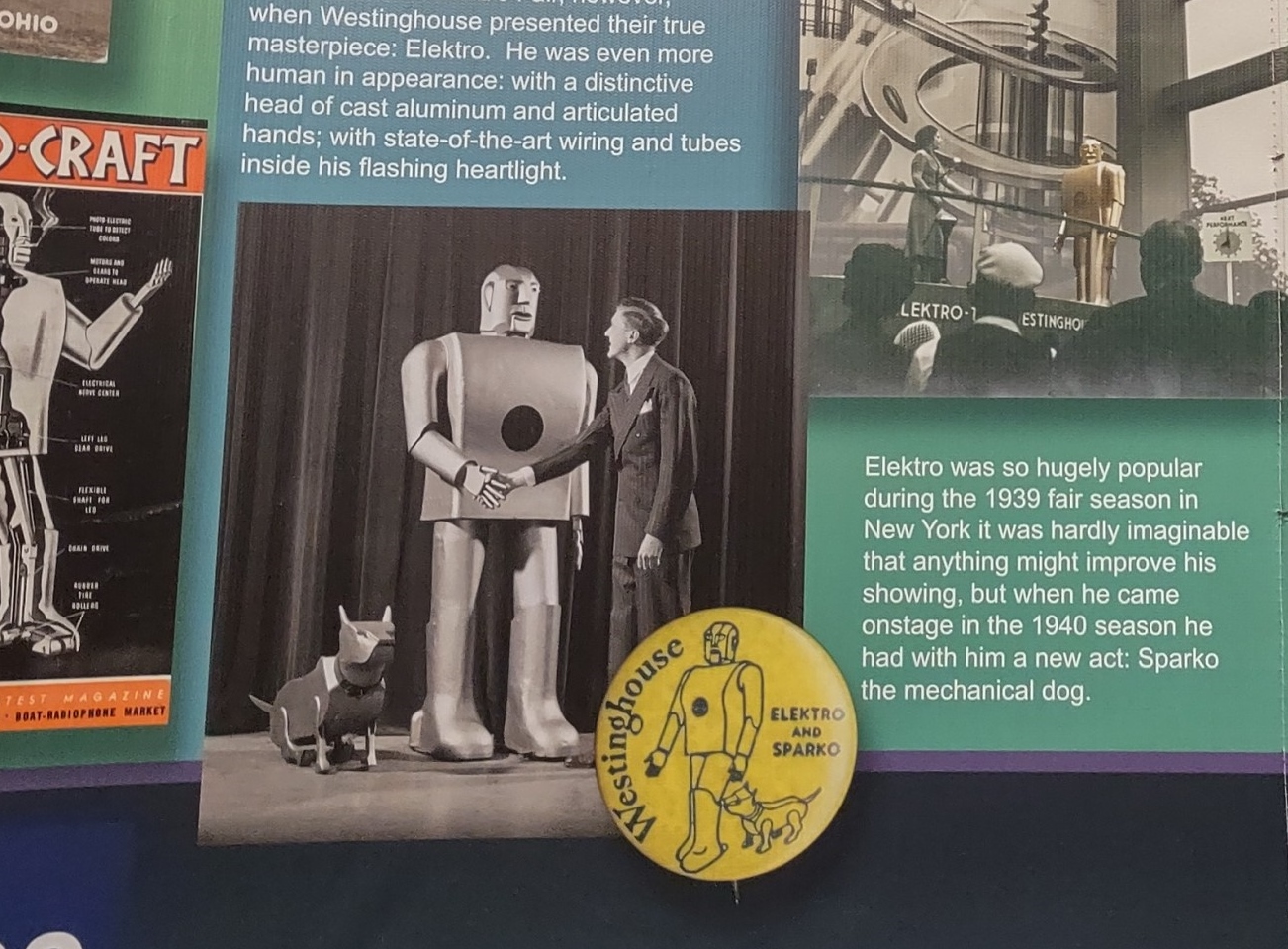

Thermodisc thermostats, Lampworks light bulbs, Hi-Stat auto sensors, Hughes and Keenan cranes, Shelby bikes, Hi-Lo campers, Martin Steel perforated steel planking, Stran-Steel modular housing, Perfection bed springs, Maxwalton Shorthorn cattle, Bur-kleets football cleats, Buckeye suspenders, Fashion Hill sweaters, and the wondrous Westinghouse Elektro sing their munchkin song along the yellow brick road of our museum. Like the Wizard behind the curtain, personal business ownership beckons, promising to take out the dreaded boss and give direct personal profit. Hard-driving risk, opportunity, challenge, and achievement add sparkle and zing to the American milkshake.

Slowly corporate descent is gathered into the hands of fewer and fewer entrepreneurs. New business holders take the risks, then sell out to the wealthy few. Careful groundwork connects freedom to consumption, and production. The museum website captures the marketing strategy that now defines the relationship between producers and consumers: game-changing technology and innovations that revise America’s assumptions about quality of life.

The universe-net struggles to define quality of life. Is it financial security, job satisfaction, personal health, material comforts, mental and emotional well-being, social connection? Our geo-trail takes us out of the museum and 10 minutes south, over the Fork River, past broken shells where new businesses have hatched, grown up and moved across town to upscale chicken yards.

Our CO is not shy. This cache is on the property of the company my family has owned and operated since 1980. Delight in ownership, productivity, hard work, innovation, and customer satisfaction radiates. We are invited in to an American success story.

Secure packaging containers, specifically cartons, pads, buildups, partitions, die cuts, and more, wrap cardboard arms around all the “things” that we will buy, eat, drink, play with, work on, and throw away today. Where it can be recycled and used again.

When the company reaches its third decade, someone inside decides to watch cachers come and go, flummoxed and discombobulated. For the next ten years, the creativity oozing from this building ramps up the quality of life considerably for Cache Nation. Black out.

In 2015, a finder records the memorial celebration of their late son’s sixth birthday. In 2021, a second finder logs her own story. In 2015, her brother taught her to geocache. Six years later, she lost him. Silent witnesses stand around us, able to hold and offer comfort across time and space, visitors to and from this private and protected place.

Financial security? Well, it’s free.

Job satisfaction? Yep, we found it.

Personal health? I’m feeling great – how about you?

Material comforts? We didn’t forget our pen.

Mental and emotional well-being? I’m still smiling over this one.

Social connection? We’re all in this together.

Quality of life? Check.

-

Turn about is fair play!

In 2008, Cache Owner Hamsquad placed their one and only cache. Fifteen years later, it is our turn to take on this teenage trickster.

At our quick stop at the grocery store, holiday decorations wave wildly at late winter skies, pointing out the obvious.

The journey north unflattens, rolling into mounding waves of farmland, where ancestral homes still root deeply into earth beneath.

We exit at Mansfield. For all the world, the sun is sparkling, fresh breezes delight, gas prices are down, and life is good. Except for the mail car. Did you see mechanical breakdowns in the list of neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night???

On an ordinary street, the CO sets a cache directly in front of their own home, to the delight of the resident ten-year-old son. For 15 years, he grows with his cache.

By 2010, finders are reporting whether they got to chat with Mom, and did they need her help, or the help of the cat.

In 2012, the angst over searching private property is recorded, as images of being questioned, shouted at, or chased flicker across the screens of memory. Oops!! I thought this was the overgrown driveway to the cemetery, not your front yard. So sorry!! No rifle needed!

By 2020 the son has graduated from college, but in 2022, Mom is again spotted and recorded. Today her dryer is running. The scent of fabric softener drifts across the lawn.

Turn about turns out to be the exact clue we need for this tricky teenager. Property records show our CO has lived here for 30 years, watching cachers come and go for half of those years.

While powerful national interests gain and spend endless streams of tax money, happiness here flows from friendship, fresh air, and the free exchange of good will.

-

Dear Diary

A six-month-old baby, placed in 2022 by Cache Owner sunchasercachers, promises to let us read the diary.

Hurtling through space, our planetary ship drags winter from Northern to Southern Hemisphere. We are fine with leaving the Arctic behind.

Hopping off the interstate at Mansfield, today’s geo-detour exits west on Route 30.

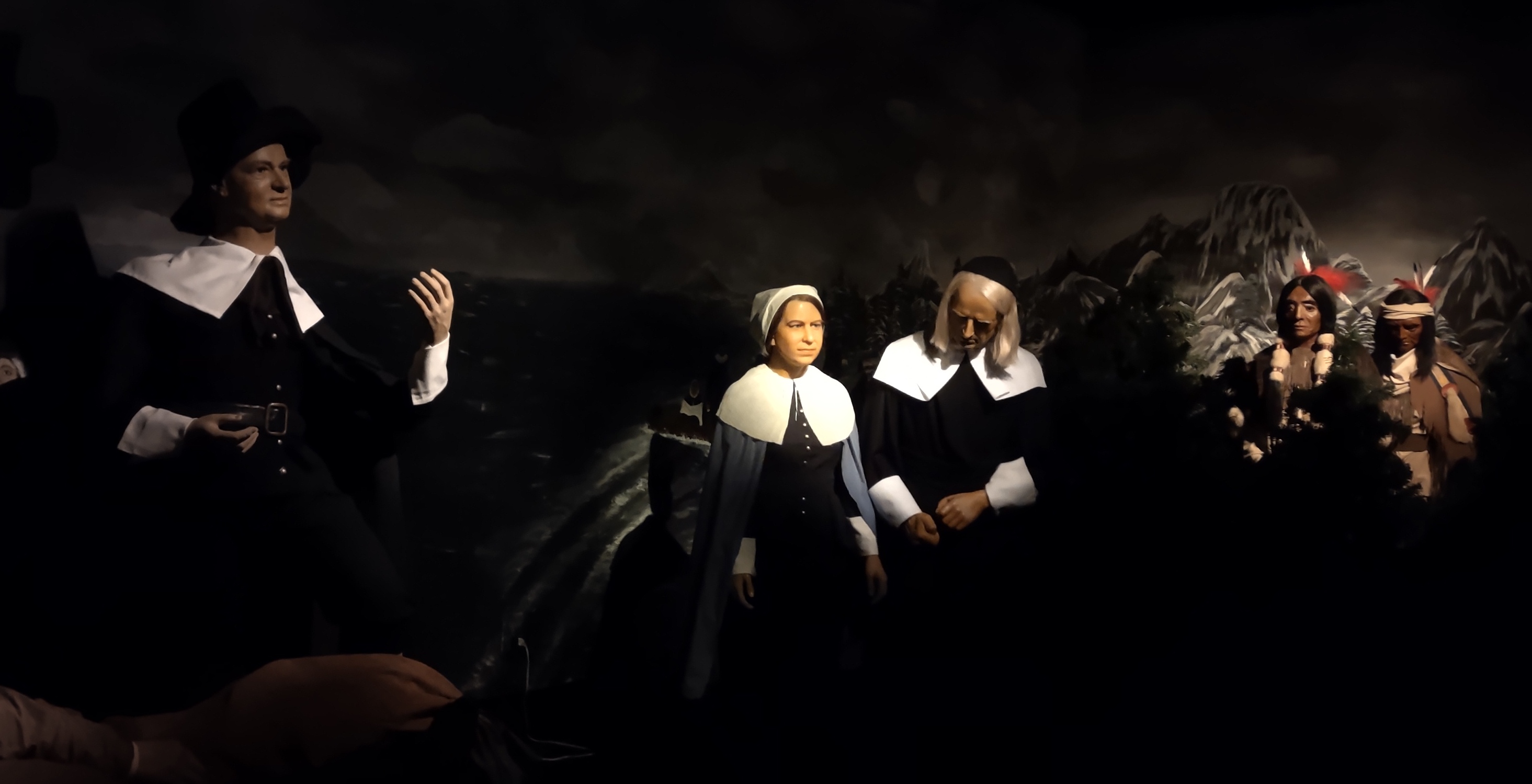

Inside the Biblewalk wax museum, 4,000 years connect with today’s pilgrims.

Creation, Fall, and Flood give way to long years of a tiny tribe of desert wanderers slowly growing into a Middle Eastern nation. Onto the scene is born a baby. The next 30 years will pose a puzzle of the perplexity of a powerful Deity joining creation as an offered sacrifice to deliver wandering humans from their wayward anguish.

A Syrian named Paul hears the voice of this Deity in a great flash of light.

Pondering it all, Paul combines decades of study with this new revelation. Turning from the powerful religious class of his day, which majors on excluding and scorning the little guy, Paul grasps the idea of individual value elevated to a new level by the outstretched hand of a Creator.

Now in prison for spreading the word of this great offer from above, Paul writes letters that will be combined into a best-seller for the next 2,000 years. A master plan, extending beyond the grave, explains the fragile and fleeting nature of human existence on a time-bound earth, bound together with a force so powerful and eternal, it is known simply as love.

It will be 1,300 years before Mr. Wycliffe translates this book from Latin to English. He feels there is something wrong with the privileges and wealth of the religious class, who claim ownership of the book. Mr. Huss goes to the stake, defending the right of the people to read the book in their own language. Finally Mr. Luther, in 1517, nails an announcement on the Wittenberg Door. He is sick of the leaders of the book, who are now called the Church, for selling salvation, exploiting those who want to read and follow the book, and giving all the best jobs to their friends. As protesters join the movement across Europe, things will never be the same.

One hundred years later, those called the Pilgrims flee the religious wars which now define the Continent. Believing that their personally known Creator has carried them across a vast ocean, they look for a land where all can worship in the way each knows best. As tribal nations are cast aside, the long distortion of simple, humble faith into religious arrogance and pietism unfolds.

In the 1700s colony of Georgia, the Wesley brothers catch on to the idea of regular Bible study and prayer. John and Charles write over 6,000 hymns and preach countless sermons. Small, white-steepled buildings scatter across the hillsides of pioneer America. Today they still wear nametags of the children of the Reformation. Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, and Lutheran eye one another from safely defined sanctuaries. When senators of 2023 refer to Tiktok as the sheep’s clothing, words from the Book echo across millennia.

Our pictures tell us that, like a mustard seed or a tablespoon of yeast, faith is lived out in a thousand ways, in the simple joys of work, food, sympathy, affection, and a game of hide and seek. We go to find our game.

Ten minutes south of the museum, just off of Lucas Road, the geo-zero rests in Lantz Cemetery. Already precocious, our baby cache description is wondering, Why? Why is this cemetery divided into Protestant here before us, and Catholic over the hill? Dear Diary, what do you say?

In a cache more American than the flag, we see unfurled the freedom to decide one’s beliefs – and how much that matters. Citizens of the sweet land of liberty hold tenaciously to the sense that there is meaning and purpose to be found and lived out, where free agency is not just for football players but marks Two-leggeds as self-governing choosers. The final resting place honors that freedom.

Names echo down the hillside – Pleger, Graber, Klotz, Kiser, Herr, Tucker, Miller, Beer, Meyer, Stover, Weber, Dzurani, Bottorf, DeCenso, Staton, Shrilla. The entangling of faith and ethnic identity adds a second page to the diary. German Lutherans gaze across the fence toward Italian Catholics.

Fallen kernels claim the promise of fresh fruit. A distinctly American identity slowly emerges, nourishing new generations, and delivering a banquet of ethnic strengths.

Finders add to the diary. Baby cache has learned to crawl and was last spotted 60 feet west of posted coordinates.

The watch-frog has things in hand. So many cool toys to occupy our little one. Dear Diary, grow strong and live long!

Across our homeward sky, messages remind that we can’t escape the power to choose, to fight or give up, to help or harm, to cache or couch-potato.

-

“49”

In 2015, Cache Owner dstricker sets a 49th birthday cache that promises to be tee-riffic.

On an early Saturday morning, our swatch of the planetary quilt snores, recovering from the previous week of rush-around.

White-winged smudges smile from on high, bringing no rain or snow down on our north-bound interstate.

With no gender bias intended, the geo-sensor exits toward our upstate neighbor.

Promising an unforgettable experience, our geo-detour begins.

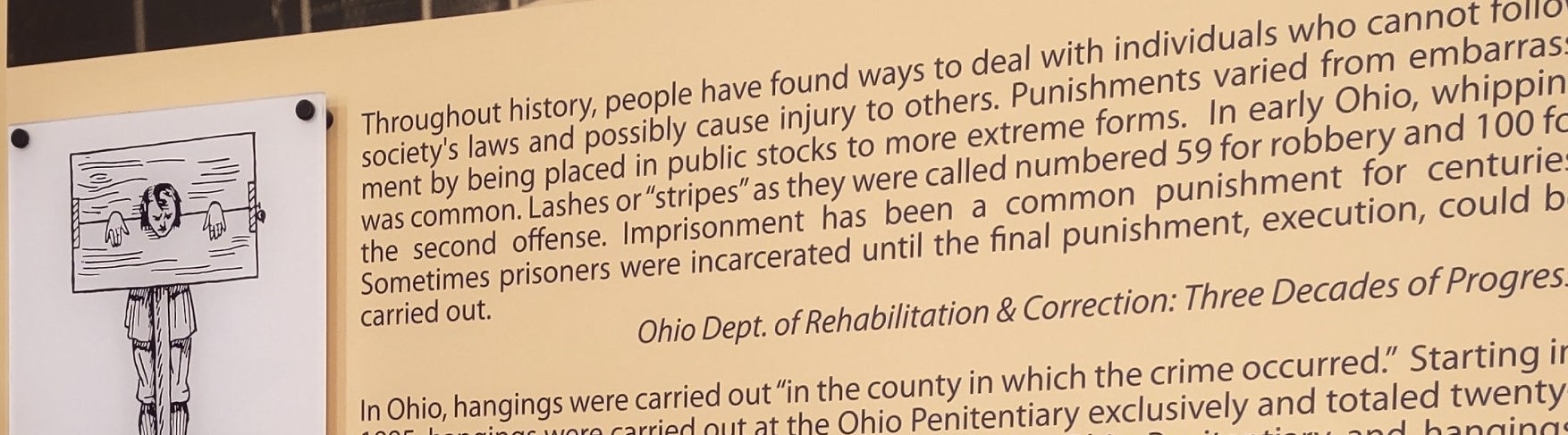

As settled eastern states and new Presidents morph legal codes from the Old World into the New, the pioneer settlers of baby Ohio deliver justice frontier style. Whip lashings, stockades, impromptu posses retrieving stolen horses and rifles, and a network of army posts write the beta code of American law.

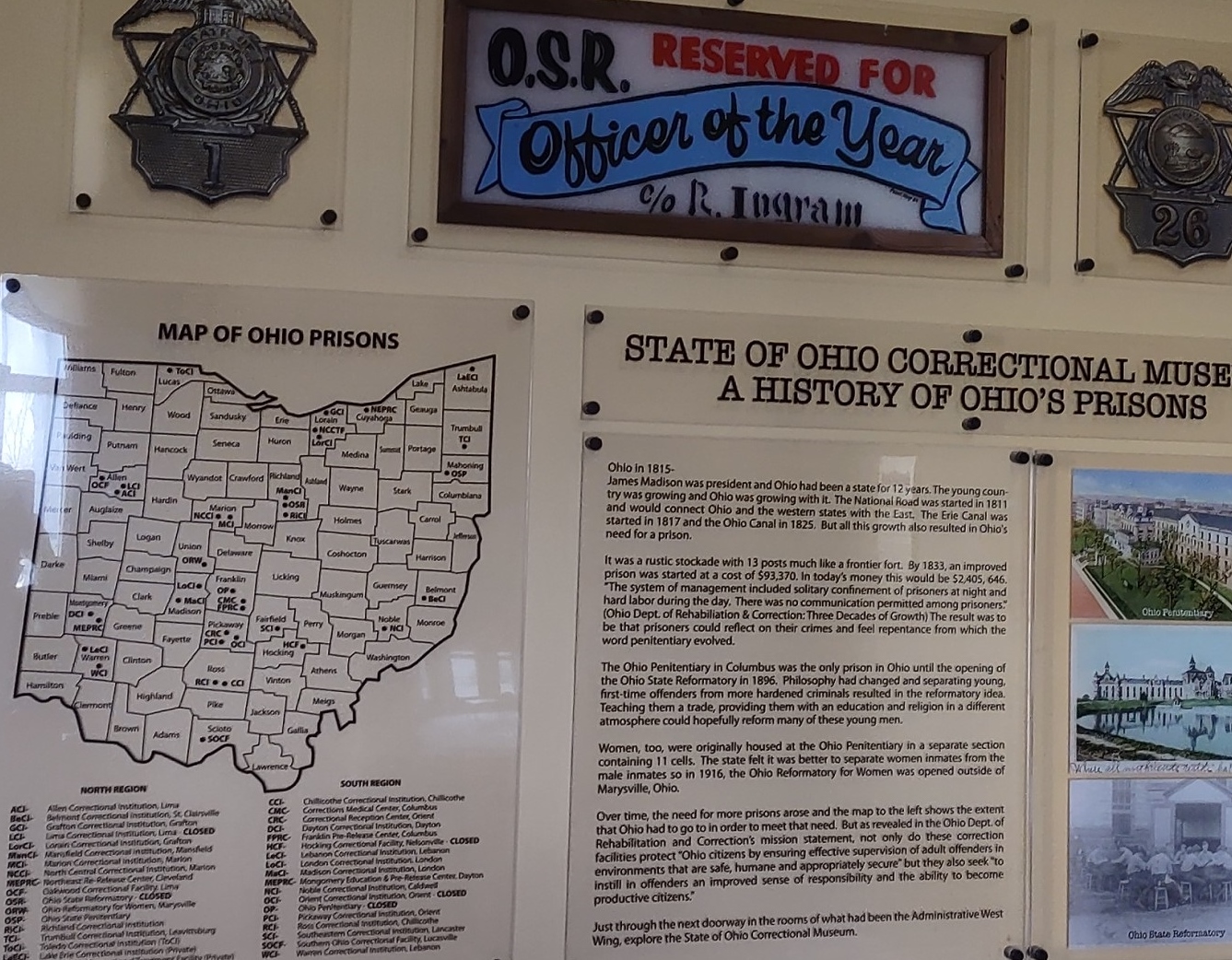

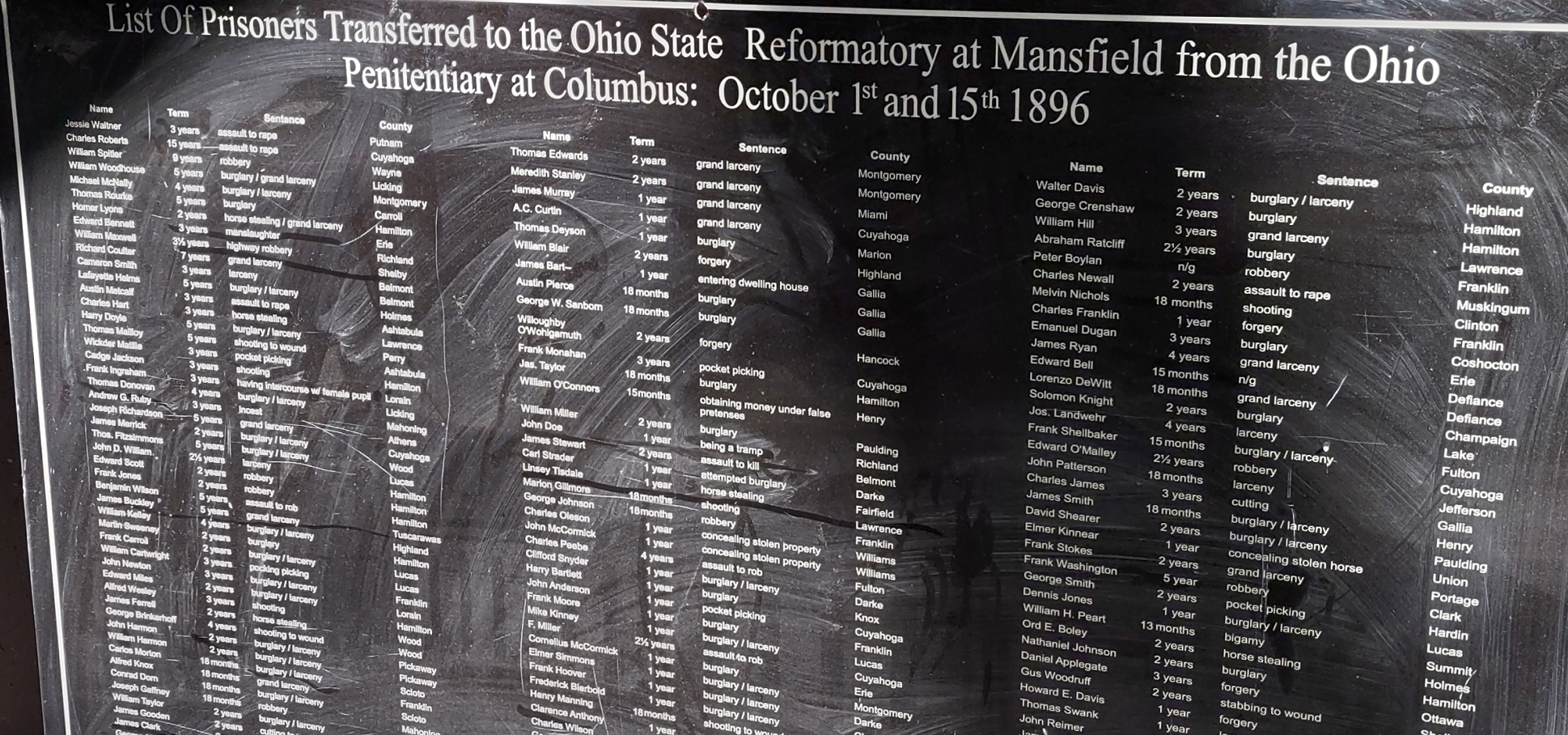

By 1815, prisoners are trying out a brand new penitentiary, designed to ensure public safety and the rehabilitation of the lawbreaker. Solitary confinement is approved for crimes inside the prison, such as assault, cursing, idleness, or disobedience.

Fifteen years later, a new prison built by inmates houses 700 cells. Income from long days of prison labor feeds the state treasury. What’s not to like? Prison profits in 1838 exceed expenses by $23,000, or, in today’s dollars, well over half a million. People of conscience, fighting to end unpaid Southern labor, sit up and take notice of this substantial source of state income on the backs of captives.

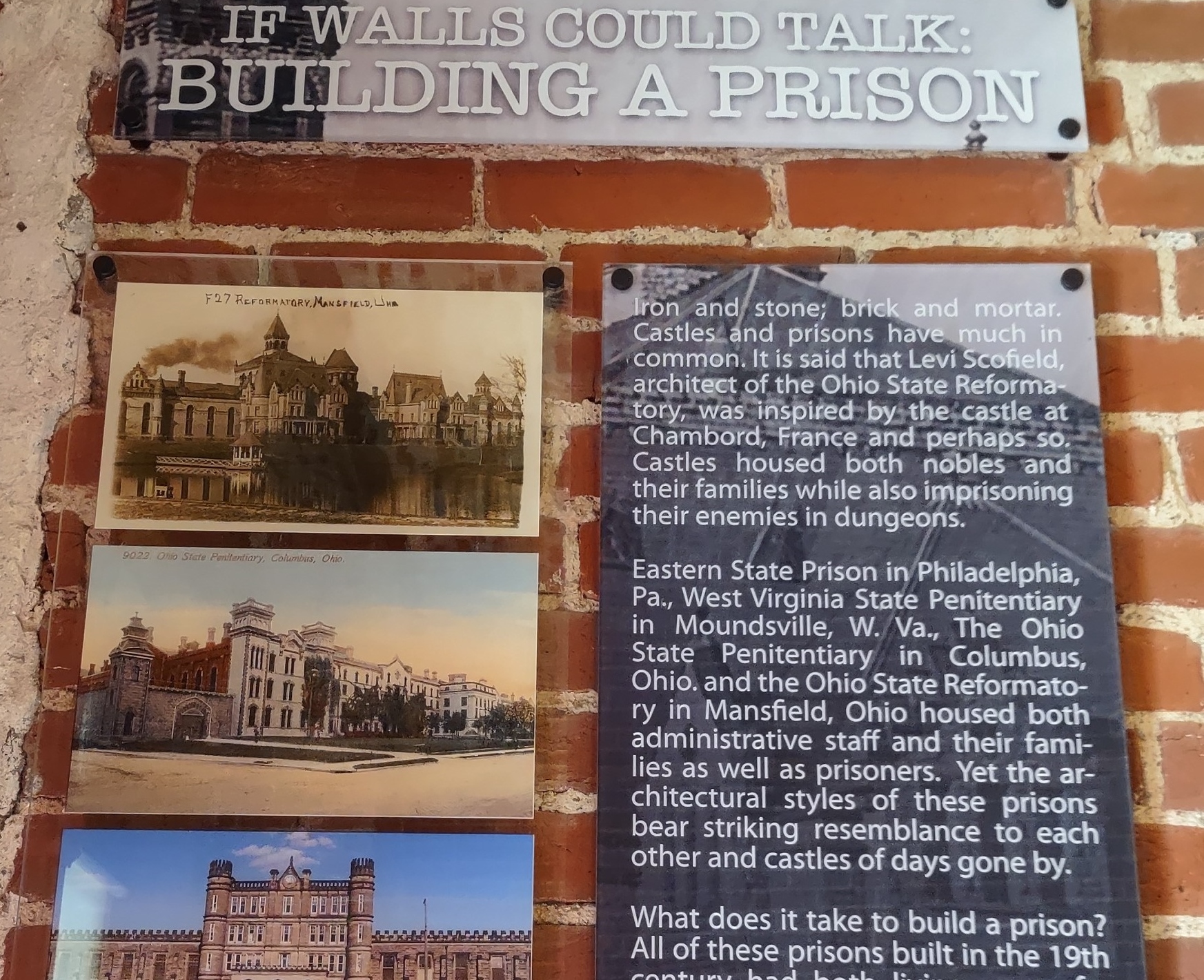

When the city of Mansfield wins a share in the prison pie, the brand new Ohio State Reformatory is built and finished in 1896. Architects envision a very different model, where minor offenders can finish school, learn a trade, and participate in spiritual development.

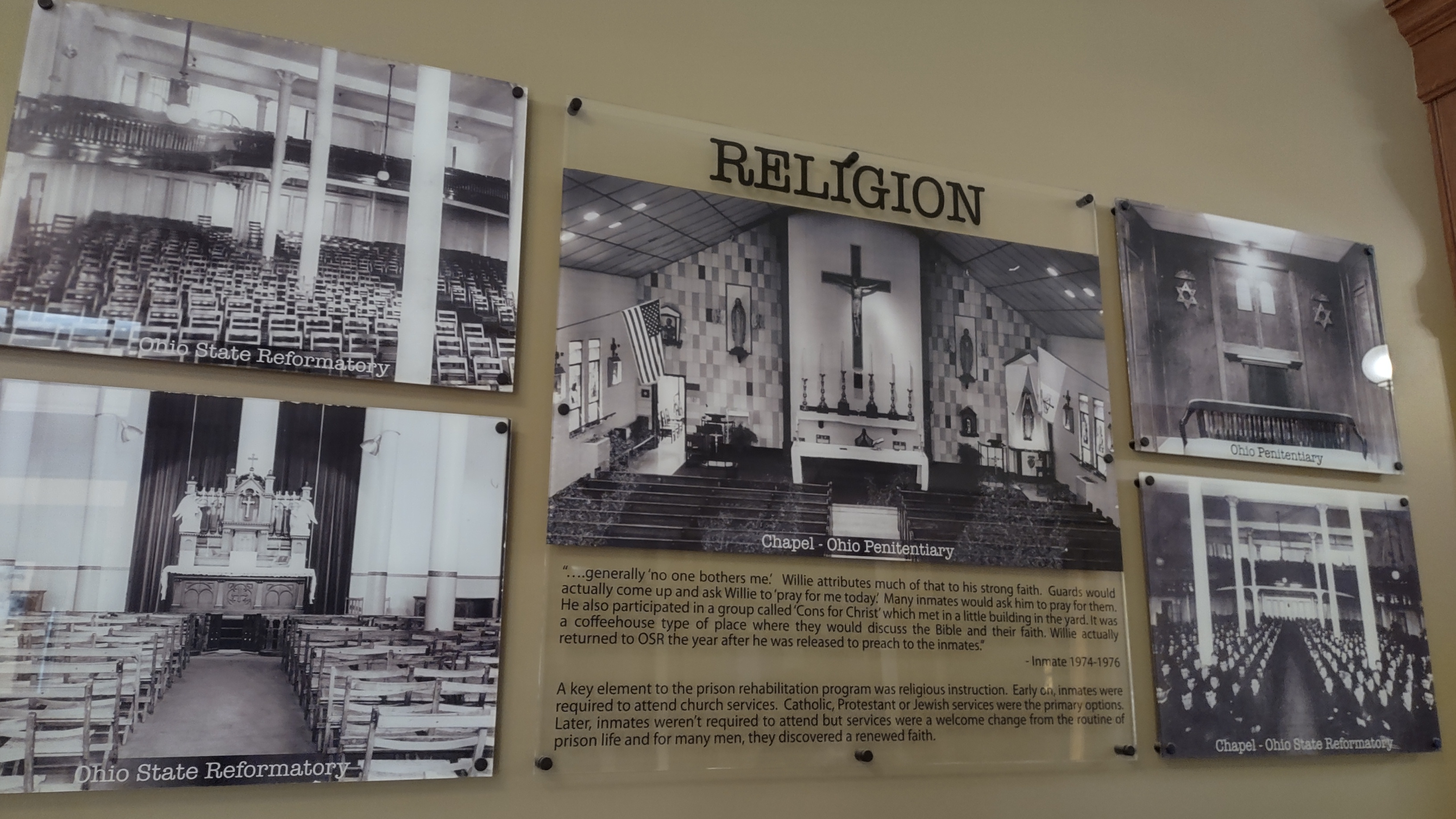

A prison farm, regular chapel attendance, and industrial training deliver the goods, bringing home an impressively high success rate and low repeat offense.

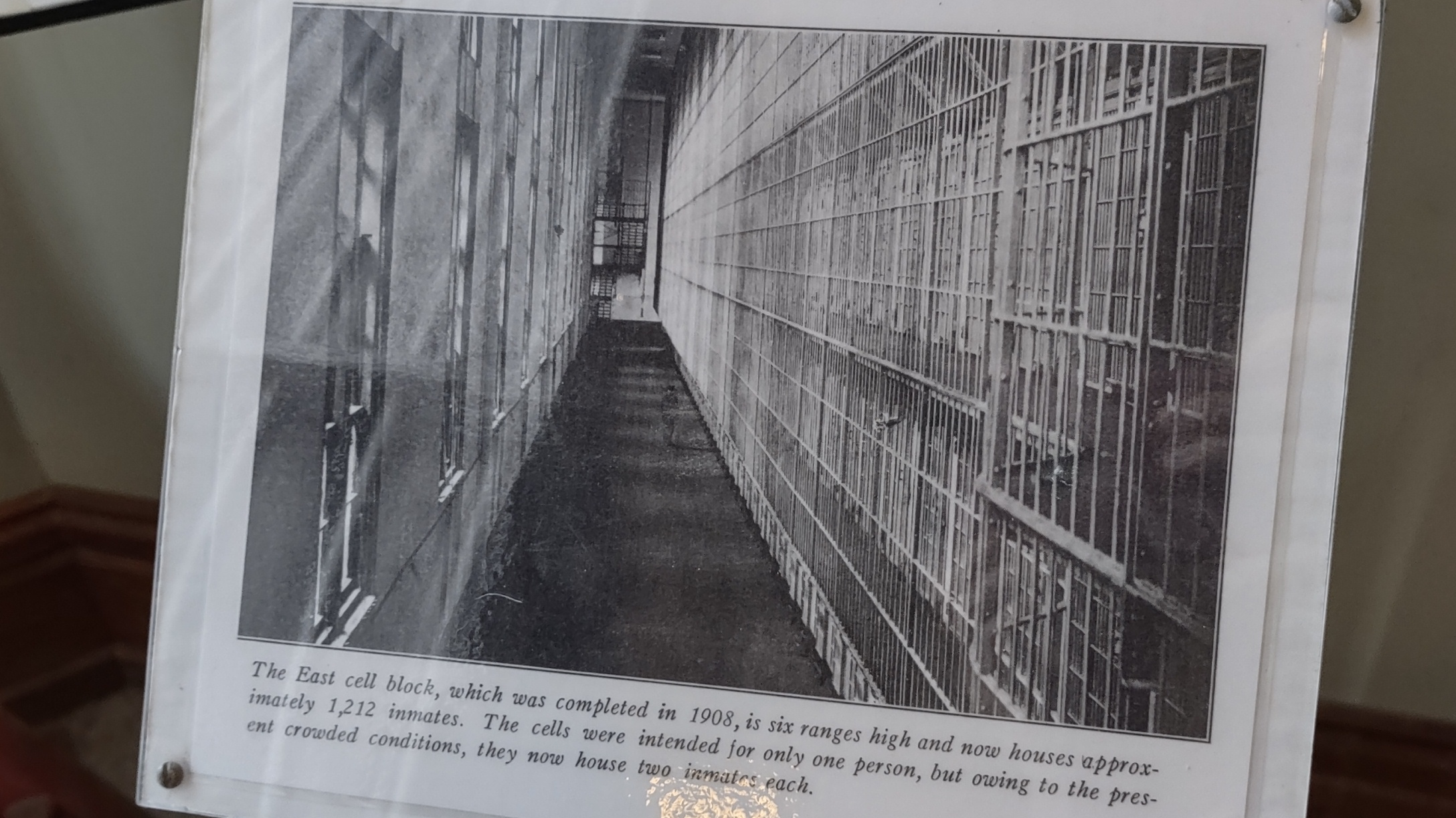

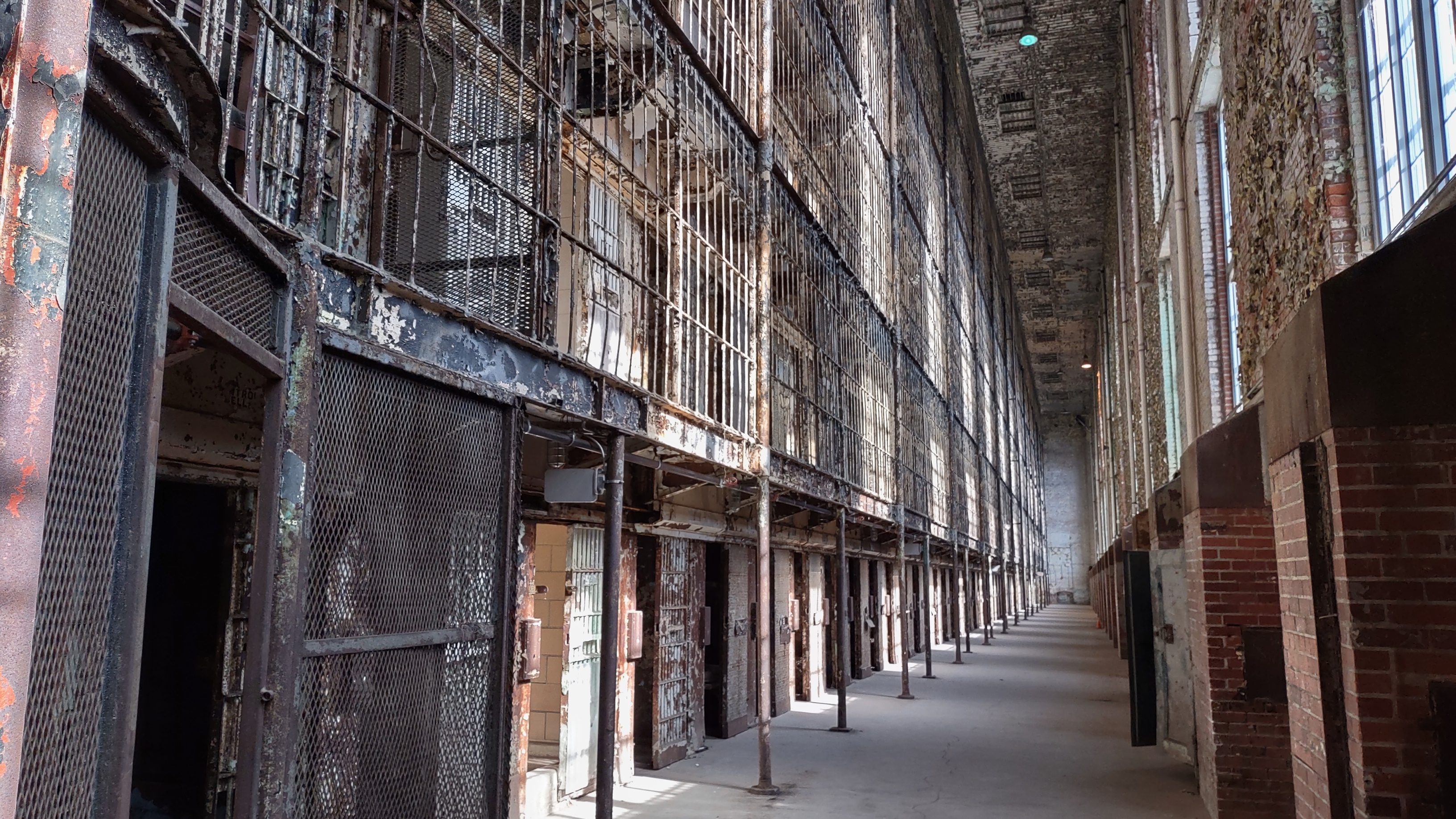

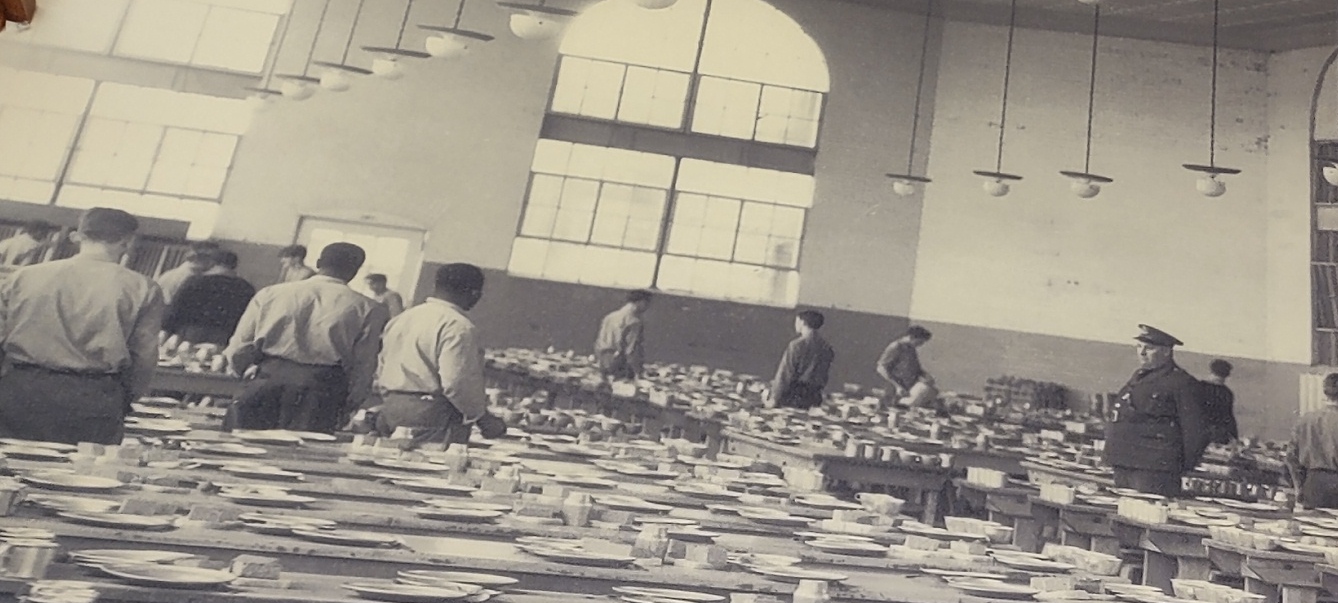

With a West and East cell block, stacked one on top of another, 1,300 inmates now fill the OSR.

Days mimic routines to return to society, making shoes, clothes, and furniture, processing meat, writing and playing music, working on a construction team, doing things never learned as children.

Inmates are paid an hourly rate. Half is saved for “Going Home.” The other half buys magazines, chips, and smoked sausage from the commissary. Intricate craftsmanship reflects inner souls. Mr. Humphrey enters for Grand Theft and leaves with a high school diploma and a resume for building houses.

In 1957, Eugene Flynt is crossing an Akron street after a long shift at the Goodyear plant. He is struck and killed by Frank Freshwaters, another 20-something auto worker. Frank is convicted of manslaughter, violates his probation, and finds himself in a cell at the Ohio State Reformatory in 1959. His good attitude takes him to the prison farm, where he slips away undetected, disappearing for the next 56 years.

By the 1960s, the Reformatory is converted to a maximum security facility, something it was never designed for. The largest free-standing steel cell block in the world becomes a sardine can. A seven-by-nine foot cell meant for one now holds two, and the population rises to 1,900.

The next 30 years will be spent in a battle for rights of those incarcerated: due process protections, grievance procedures, access to legal materials and law libraries, reintegration support, educational programming, parole eligibility, care of terminally ill inmates, the ethics of prison snitches, crime victims’ rights and protection, and definitions and penalties for felonies, in the context of public, staff, and inmate safety.

When the full-fledged Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections is born in 1972, Bennett Cooper becomes first Black Director of Corrections in the nation. He supervises 9,000 inmates across seven institutions, with 8,000 parolees and 3,000 staff.

Within four years, the number across the state sky-rockets to 12,000. Cell-crowding becomes a norm. $250 million is budgeted for new prisons situated closer to cities where inmates can maintain family contacts, the greatest predictor for successful reentry.

By 1975, Frank Freshwaters is now William Cox. He has lived in West Virginia for 15 years, fishing, tinkering on cars, fathering children, driving truck, and eating cold chicken. When Ohio finally catches up with him, WV covers for Frank long enough for another escape, further south.

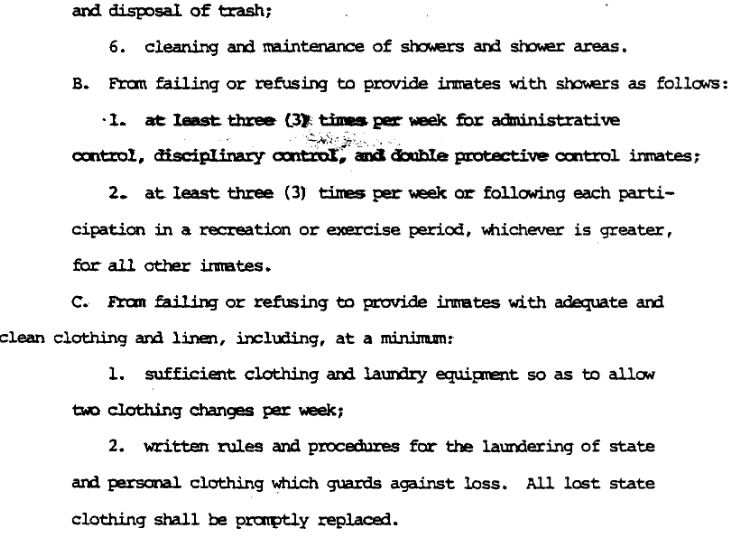

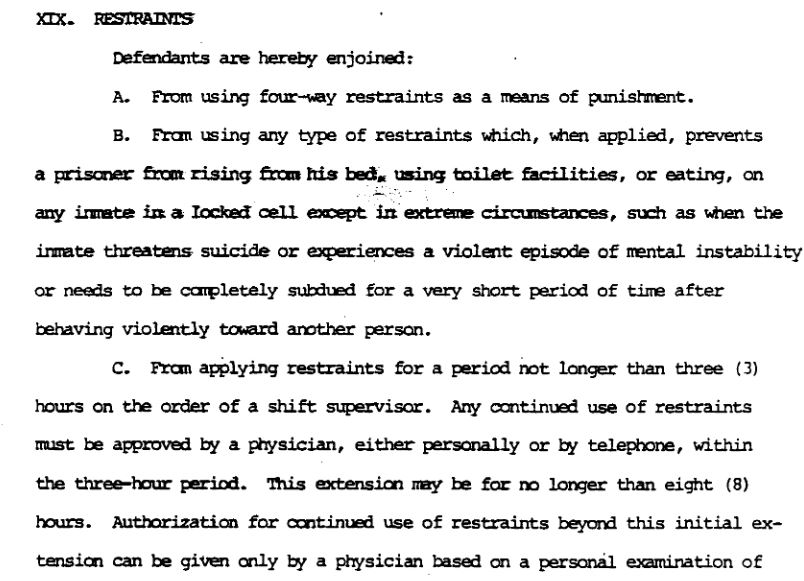

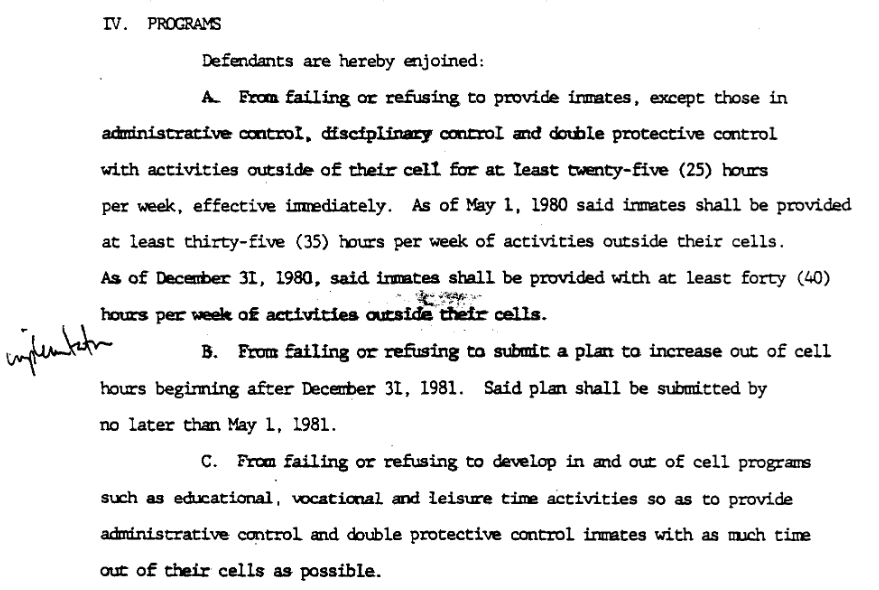

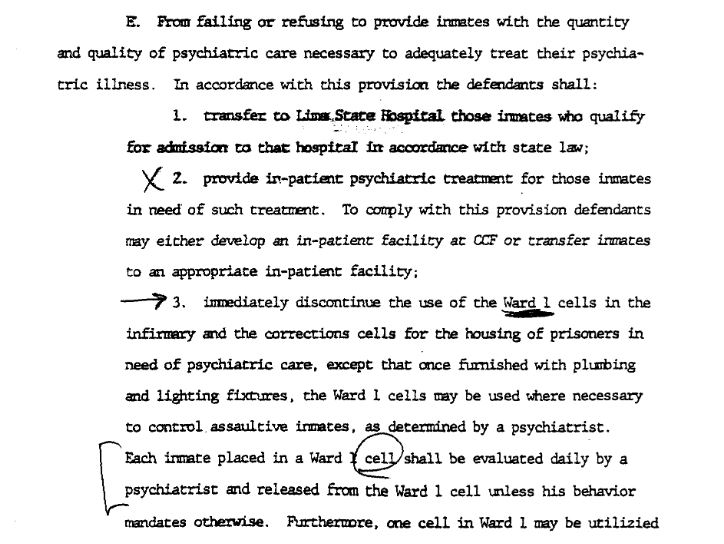

In 1978, the US Supreme Court limits public access-on-demand to penal institutions. That same year, four residents of the Ohio State Reformatory dust off a 200-year-old document. There they find that the United States Constitution not only guarantees equal protection under the law, but also prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.

With Constitution in hand, Boyd vs. Denton initiates a class action complaint to remedy overcrowding, racial segregation, physical deterioration,

inadequate showering, heating, and cooling, and rodent infestation.

In 1979, Stewart vs Rhodes is settled with a consent decree, mandating time, space, and equipment for exercise and recreation, noncrowding in cells,

justified use of physical restraints inside a locked cell, sanitation and clean clothes,

operational plumbing, light fixtures and temperature control (heating, ventilation, lighting, plumbing and water), fire safety, psychiatric care, access to legal research and law interns, writing materials, disability accommodations,

voluntary work assignments, mail delivery, reading materials, approved visits and access to telephones, religious services and consultation, non-racially-segregated cells, and applications for transfer to lesser security institutions.

Two years later, Rhodes vs Chapman, also a class action against cell crowding, works its way to the US Supreme Court. Federal justices consult their consciences and decide that, “To the extent such conditions are restrictive and even harsh, they are part of the penalty that criminals pay for their offenses against society.” The court feels good about relying on the judgment of state legislatures and prison administrators, “who surely are not insensitive to the requirements of the Constitution.”

It will not be until 1983 that Boyd vs. Denton works its slow way through the court. A consent decree is approved to close the OSR permanently in five years. Extensions are granted for another 17 years while two new facilities are built.

For two inmates, that time is not soon enough. In the spring of 1990, they pinpoint a no-longer-occupied section of the West Wing. They pry back a metal plate, open a door, remove a six-foot metal support bar and use it to pound a hole through an outside wall of a deserted prison dormitory. Debris is stuffed into mattresses. The crash of weights in an exercise room nearby covers the regular pounding of a hole expanding through the wall. Train tracks and a highway are a short jog away.

One day, Officer Ingram walks through the deserted hall. He wonders why a blue sweatshirt is hanging on the wall. When he moves it aside, a gaping hole and one bit of cornerstone rests between two industrious inmates — and freedom.

Later that year, the last prisoner walks out of the OSR. 20,000 people attend the ribbon-cutting for the Mansfield Correctional across town, population 2,200, with both general security and max compounds.

From the window, we watch black-suited inmates at Richland County Correctional next door. Residents pace out rounds on the sidewalk or gather in clustered groups. Security guards walk to their cars and drive away.

Left behind in the old Gothic Reformatory flickers a 36-foot-high, solid gold, completely invisible trophy, inscribed Most Haunted Prison in Ohio . . . or maybe the World. Over 200 prisoners perished while incarcerated. Noises, perfume, and other paranormal activity, attributed to deceased residents of this sad and weary place, now draw curious spectators. Hunting ghosts throughout the reformatory, by day or night, costs $99 and includes pizza.

By 1993, Lucasville, south of Columbus, has become the home of a maximum security prison, with 1800 residents, including 300 suffering from severe psychological disorders. On Easter Sunday, with low staff levels, 400 prisoners in the L Block seize batons from guards and hold eight guards hostage for 11 days. Nine inmates and one guard will die before a surrender is called with a 21-point settlement. Prisoners ask for more Black guards, better jobs for Black inmates, religious vaccine exemptions for Muslims, contact with the news media, and firing of the warden.

As inmates are brought to trial post-riot, the elephant foot of the state crushes with deadly precision. Disparity of resources between prosecution and defense is public knowledge. A Special Prosecutor tells the public defender that prisoners should not have counsel prior to indictment because then they would not incriminate themselves. Volunteer attorneys are informed that they may only represent clients if they arrange plea deals.

Prisoners recount interviews with the Highway Patrol in which they are told to incriminate three specific inmates for the death of the guard, with little or no material evidence. Popcorn and movie parties are arranged to get prison snitch testimony to agree. Parole is extended by decades for informants who testify for any defense cases.

Not until 1995, and another hard-fought court case, will mental health treatment be mandated in prisons, especially for the severely ill.

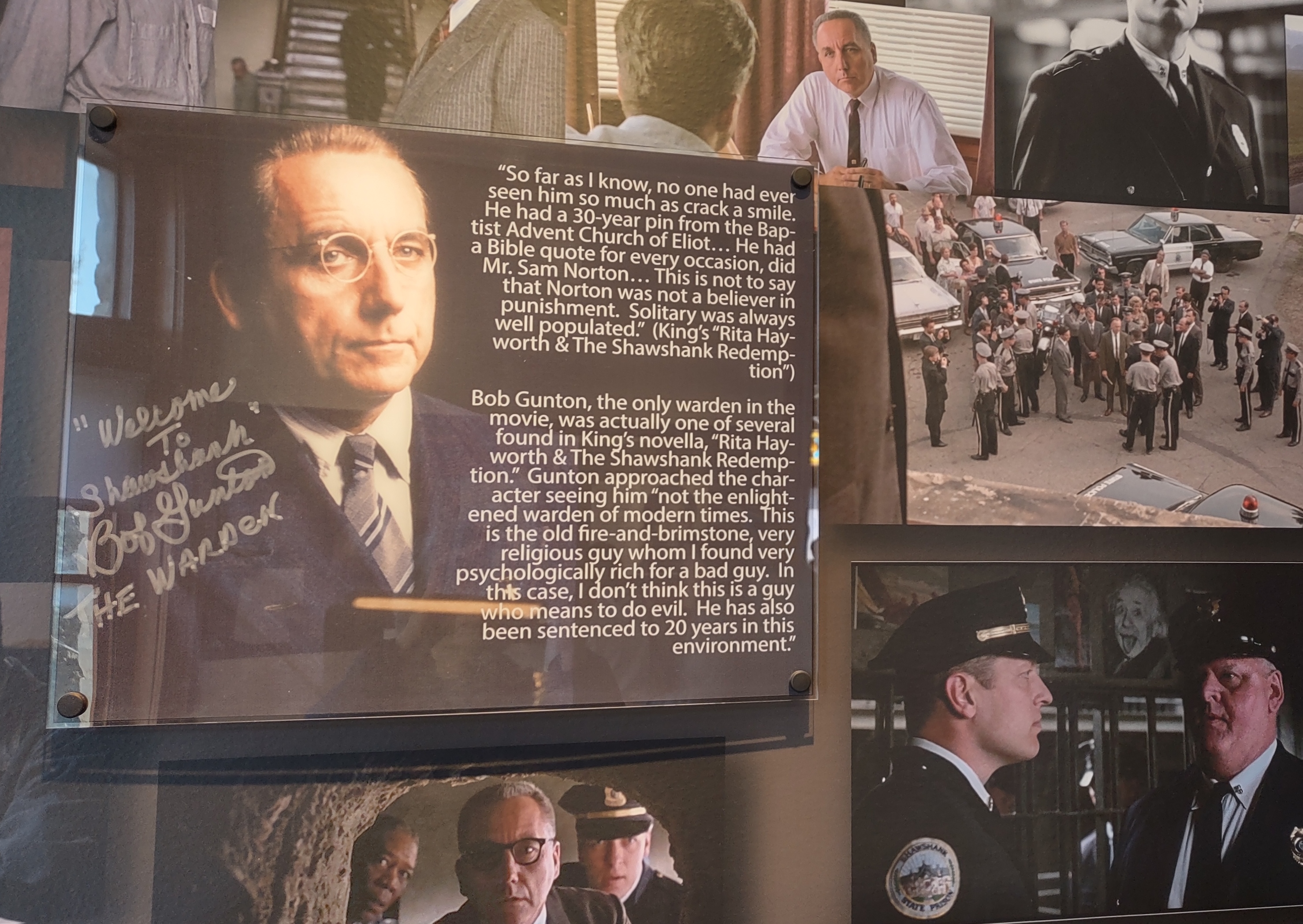

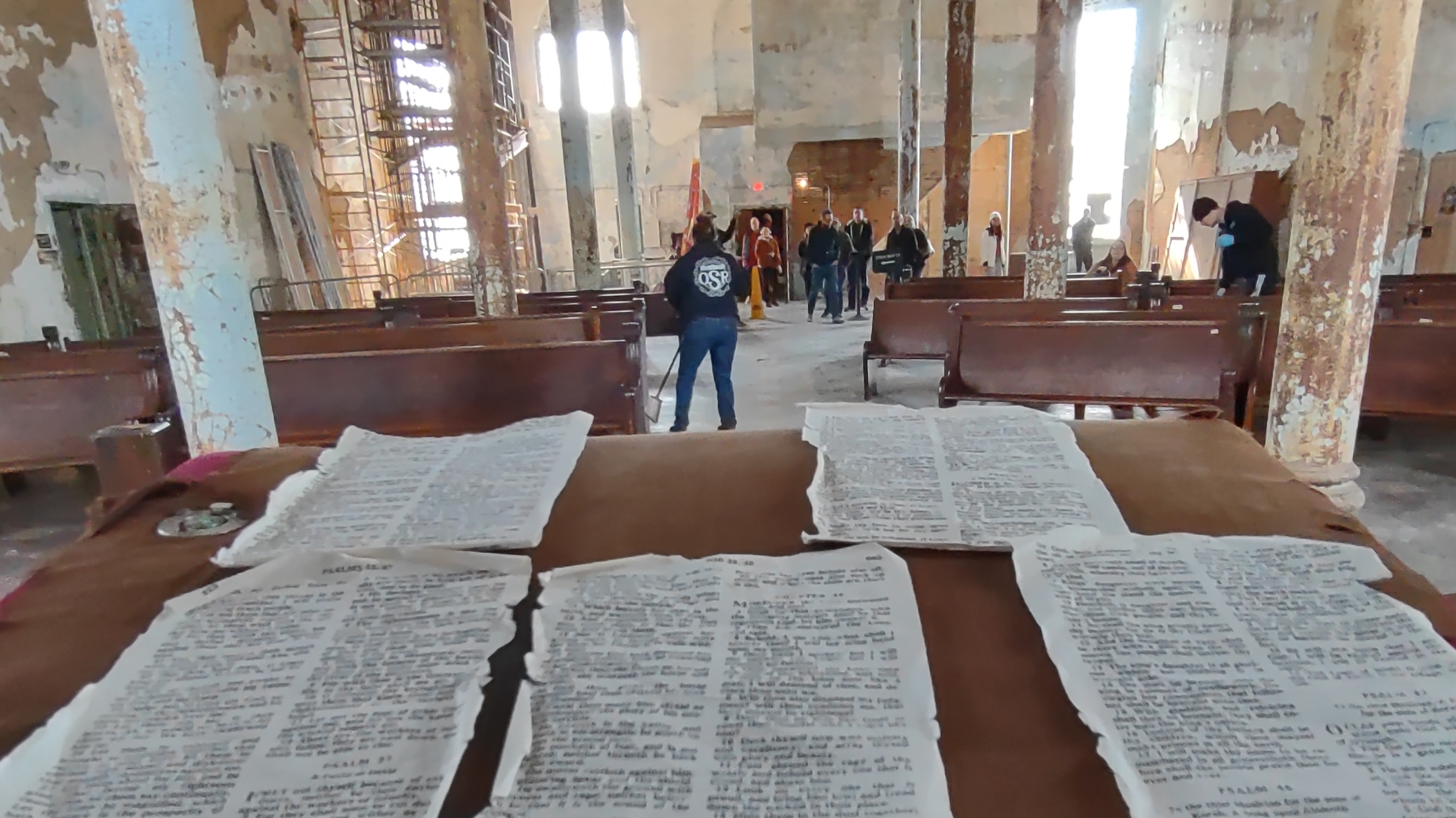

A prison built for dramatic backdrops does not escape the notice of Hollywood. Sweeping Romanesque and Queen Anne architecture thrills a director looking for a movie set. The story of one man’s war against the system comes to Mansfield.

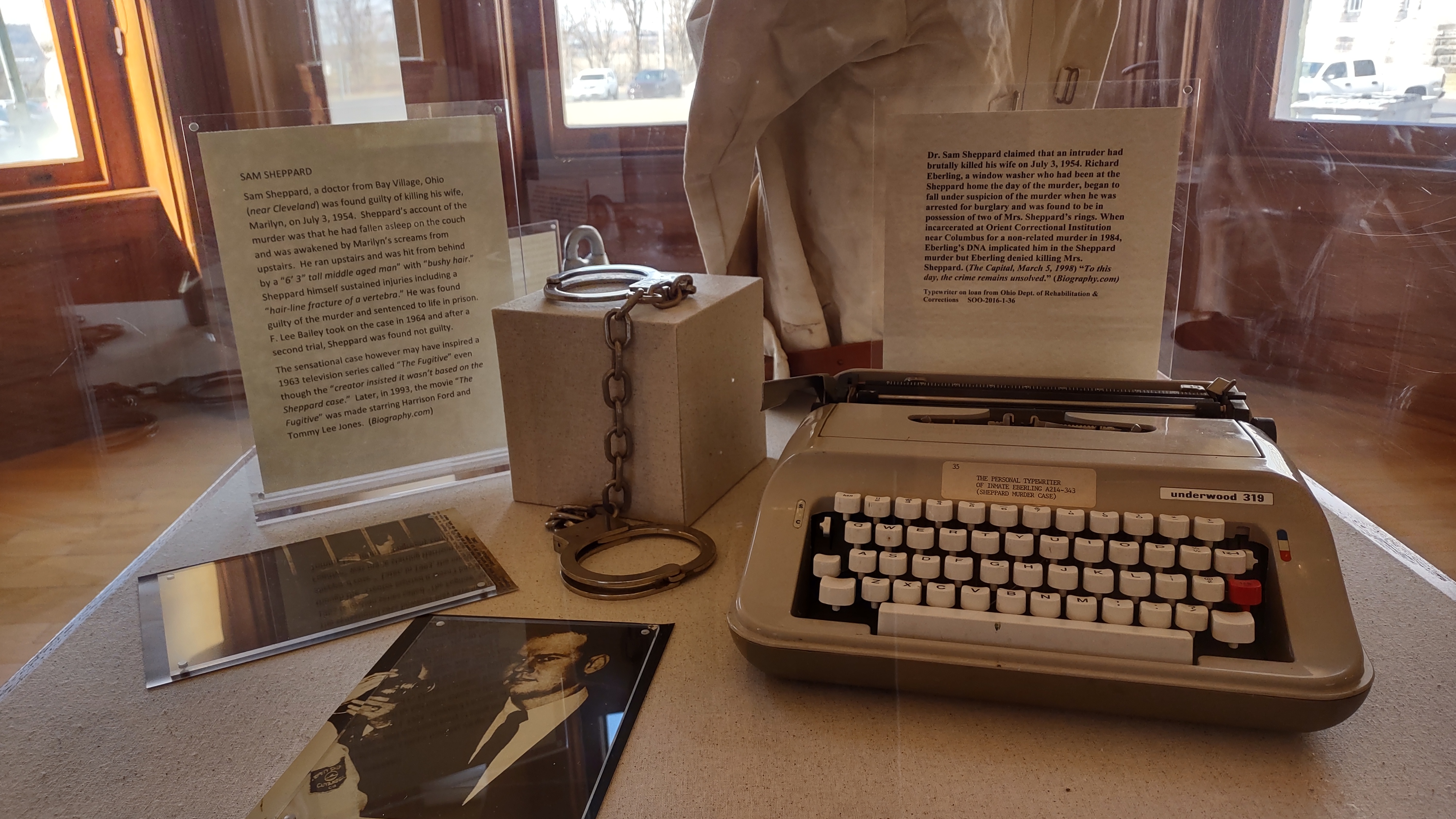

Mixing Sam Sheppard’s fight for justice, Harrison Ford’s riveting portrayal of Sheppard in The Fugitive, and a 1990 legendary blue-sweatshirt coverup, Director Darabont chooses the OSR for The Shawshank Redemption.

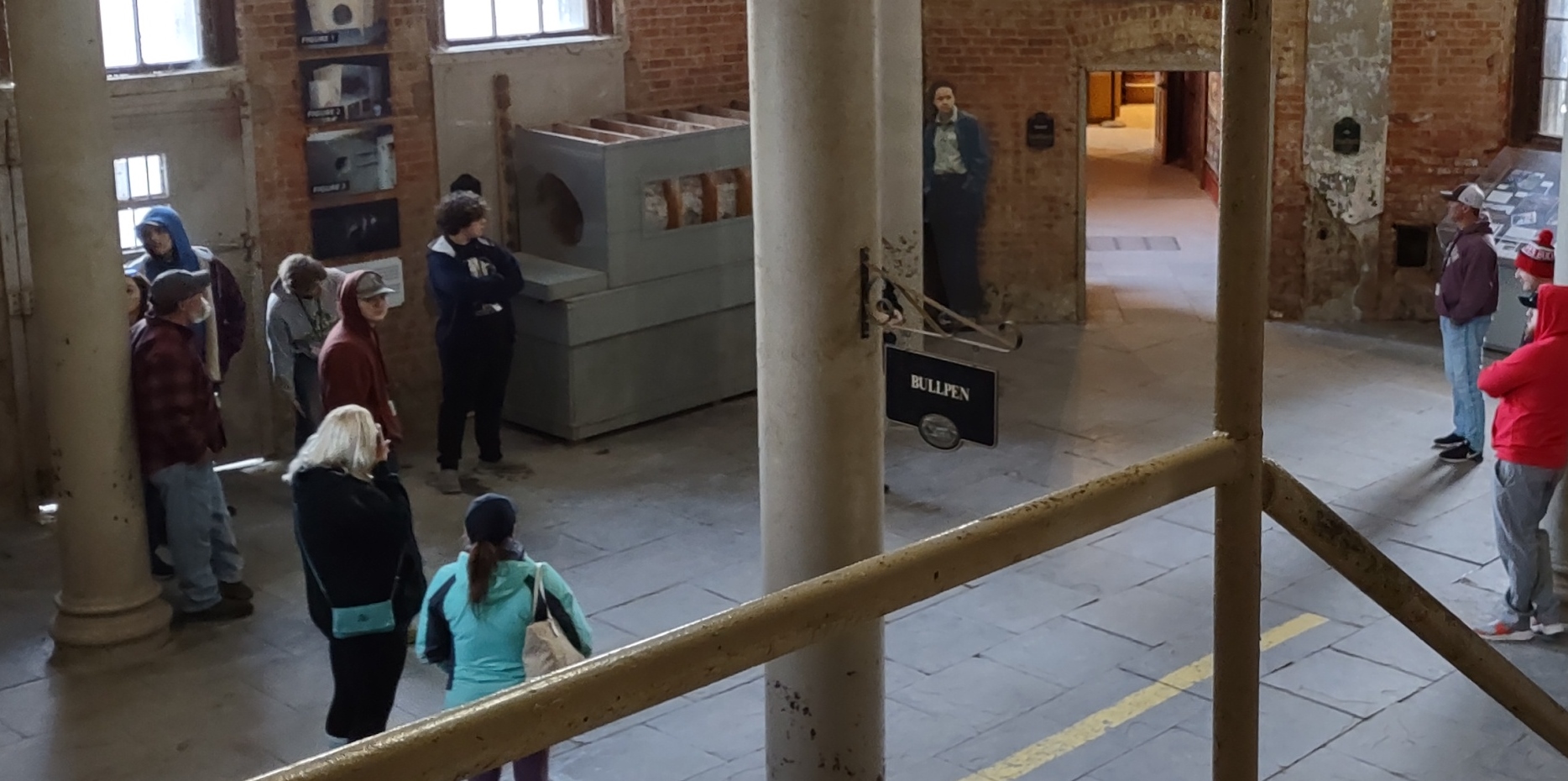

Tours gather round, where chocolate and marshmallow syrup morphs into a sewage-covered escape tunnel, and lines blur between screens and reality.

Thoughts fly through isolation cells, cleaned and sanitized to meet the demands of outtakes and scripting.

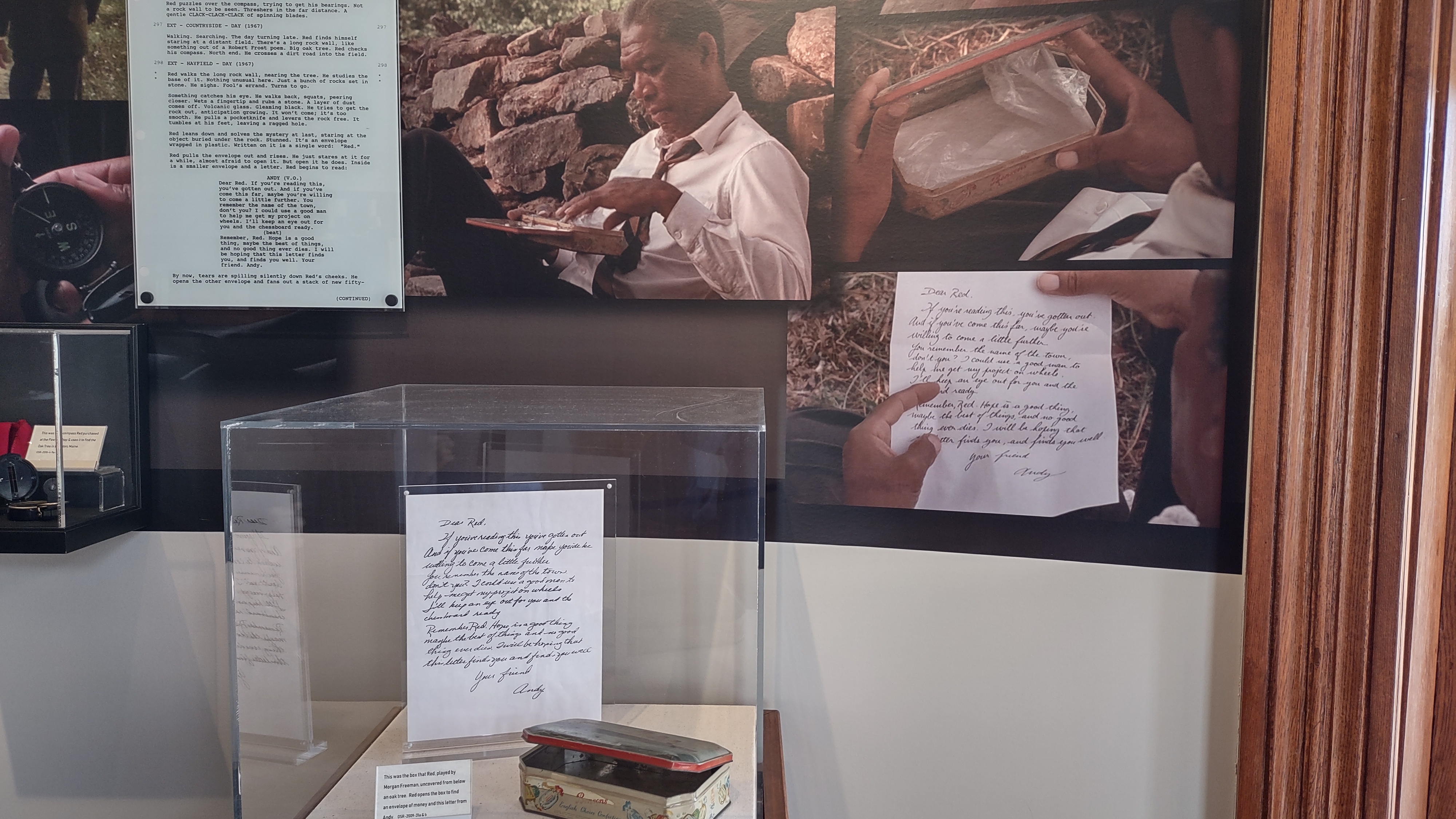

The warden, wall-papered in layers of religion, threatens, preaches, cheats, moralizes, tortures, sermonizes, degrades, and versifies. A Bible takes center stage, hollowed inside to hide a small pickaxe. Over decades, the pickaxe hacks through a wall, creating a tunnel, coated with chocolate syrup, where our hero escapes.

His letter sums it up, “Hope is a good thing.” In this movie, hope is based on luck, determination, and inner fortitude.

Not so In Real Life, where hope flies on little bird wings, beyond the walls to faces and arms which shelter and cradle.

Prayers are shared and encouragement is passed from one to another, anchored not by a pickaxe but a Bible.

Each worships according to the dictates of his own conscience. Gratitude for human connection to an invisible world blossoms in offerings of the heart.

Today’s Chapel visitors summon the spirits of 1,200 men called to contemplate.

By 1999, the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction clocks its first reduction in inmate population.

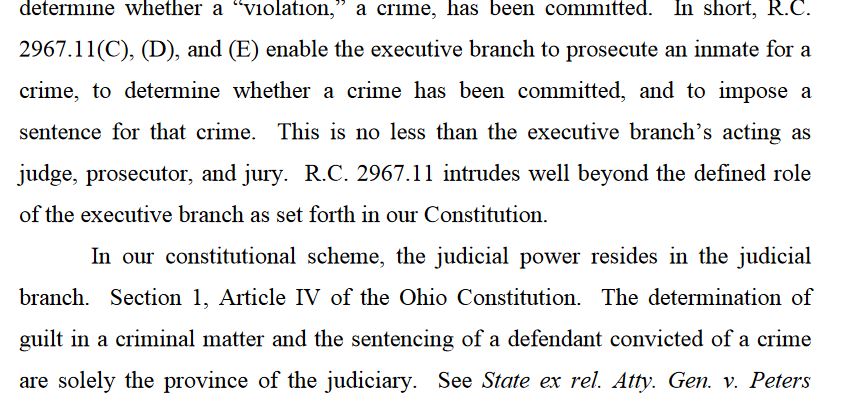

A year later, Bray vs. Denton declares bad time — adding further years of sentencing for offenses in prison – unconstitutional. A 200-year-old separation of the executive and judicial branches dictates that the executive may only carry out, not adjudicate, judicial sentences. Clutched in hands behind bars, the Constitution does not disappoint.

On the 30th birthday of the ODRC, offender reentry programs are demanded by public outcry. Across 33 institutions, 45,000 inmates and 32,000 parolees must be restored to their communities.

Now reaching the ripe age of 50, in 2023 the Corrections website envisions reentry savings accounts, body scanners, enhanced staff environments, visitor spaces, violence and drug prevention, surveillance cameras, crisis response teams, post-time jobs and training, peer support, violence risk tools, increased parole staff and navigators, and updated virtual programming.

Two decades after The Shawshank Redemption scripts Andy’s disappearance into a Mexican coastal town, US Marshals match up fingerprints with a 79-year-old man named Frank Freshwaters, living in Melbourne, Florida. He is arrested and charged with escape, ID fraud, and Social Security fraud. As real-life melts into Hollywood, a nation waits in suspense for the fate of “the Shawshank fugitive.”

Questions of innocence, guilt, time served, good behavior, 56 years as a productive citizen, justice for the victim, and public accountability occupy the parole board and people of Ohio. In 2016, Frank is released on probation into the care of his friends and family.

In 2020, the Ohio Innocence Project helps to gather evidence and defense for Isiah Andrews. The OIP proves that after 45 years of incarceration, Isiah is innocent of murdering his wife. Isiah walks back across the thin line between freedom and incarceration. Altogether, the 30+ persons helped by OIC have served nearly 600 years in prison for crimes they didn’t commit. Voices call out for a country of conscience to stop wrongful targeting and convictions of minorities and the already disadvantaged.

Citizens of the 21st century wrestle with a justice system that can free the guilty and take away an entire lifetime of the innocent. Civil codes for guiding law enforcement and insuring public peace are brooded over. Walmart closes its last two stores in Portland, Oregon, losing $5 million during a long year of shop-lifting and theft. For the wealthy, high-end protector dogs are costing as much as a Mercedes Benz. Across a nation, a 250-year-old document stretches and strains in the tug-of-war between truth, justice, and human iniquity.

From north Mansfield, we turn south and east, to a simple spot on Route 39. Immensity of open country counts the last days and hours to the homeward arrival of insect chorus, green flood of underbrush, and multitude of leaves settling at last on waiting branches.

Past laughter encircles our cache. It is awesome, creative, unique, fun, cool, and cute, echoes Cache Nation. With a perfect putt, we hit our hole-in-one.

Sunshine warms, shadows lengthen, all that we have seen today comes to rest.

-

100

Anticipating the geocache to tame,

We suspect muggles may lie in wait,

Little knowing their possible fame;

We swoop for the prize and do not hesitate. -

Tour the Scioto Audubon Metro Park

To Cache Nation, numbers matter. Smileys tick upward, slowly or at the speed of light, depending on the geodriver. Caching anniversaries, milestones, and FTFs weave into personal identity and achievement across a geocaching planet. Without further ado, today is #100 for Ohlog. YES!!!!!!!

Although thank you seems a bit weak for all we have been through together, we extend our heartfelt appreciation to geo-voyagers who are following this blog and joining us on this journey of discovery, adventure, pondering, and play, across the land we call home. Today we celebrate with a multi-cache.

As we head south, messages from the government, channeled through ODOT, give valuable opportunities for probing the minds of our elected officials. Ideas, anyone?

Returning our minds to ourselves, we contemplate the business of brains, and the push for resilient, productive, and optimistic citizens unbothered by the pains of life. Alongside runs the parallel business of inventing tonics for slackers. Our day promises to hold a 100% effective remedy.

As northern districts morph into downtown, Buckeye red blossoms. This month’s Big 10 Tournament and March Madness mark the third anniversary since all was silenced.

As northern districts morph into downtown, Buckeye red blossoms. This month’s Big 10 Tournament and March Madness mark the third anniversary since all was silenced.

Like sight restored to the blind, each new spring reminds of the bounty of communal gathering, shared food, and babble of voices. A normal Saturday, in the back of the mind, feels like Christmas morning.

Our geotour parks us in a winding bend of the Scioto River, where a 160-acre nest of birds and Two-leggeds shelters under the protection of Audubon Ohio and Columbus Metro Parks.

As the Olentangy merged with the Scioto, and both continued their dance in winding half-circles through downtown, money makers of the 1900s sized up the golden land within the southern bend. They built factories, rail yards, steelworks, warehouses, incineration furnaces, and impound lots. At the turn of the century, industry got up and left the restaurant, leaving behind stacks of old buildings, dried up scraps of storage tanks, and a tablecloth soaked with lead and arsenic.

Mr. Urban, CEO of Grange Insurance, living up to his name, stepped in to take care of his city. For six years he worked with Audubon Ohio and Columbus Metro Parks to raise capital, restoring 160 acres of very sick soil.

Together they designed a living model of a natural space within their city, sustaining the land beneath, and bringing that land within reach of 53 surrounding urban school science programs.

In 2009, the park opened, with the first Audubon Center ever built in a downtown area. A roof covered with plants, and a system of drains, rain gardens and porous surfaces deflect runoff from the Scioto. Bird corridors, nestled in the riverbend, welcome yellow-crowned night herons and 212 other species of birds.

Eight years later, Cache Owner hankpixie dangles the promise of something special with a multi-cache tour of Scioto Audubon. There are four stops ahead to uncover each piece of the puzzle. We. Are. In.

First stop: Invasive Species, aka can you believe how high the river is??? Early spring rains wash wrinkles and sleepy creases clean from a long winter nap. Clouds of morning cream, served with streaming coffee, wink back at us.

How many pictures on that sign? Seven. Don’t lose that number.

Second stop: Heather’s Tree, behind the Nature Center. A white mulberry older than its own recorded history, saved by Heather, who built the nature center around it. What year was it? 2009. Don’t lose that number.

Third stop: Wetlands. Biological diversity doesn’t sound like a viral video. We will have to pause and look. Reeds and cattails shelter millions of tiny eyes peering back at us. Land and water meet and greet through brushy filters.

How many tadpoles on the sign? Two. Don’t lose that number.

Fourth and last: Whittier Peninsula. At geo-zero, short and tall Two-leggeds carry home robin song, redbud bloom, river gush, tree whispers, sun sparkle.

Finders report that the sign is getting smudged. Numbers are disappearing. Our CO tour guide isn’t giving up. Find the unsmudged year when this park was first envisioned and partnered among three key power brokers. 2003. Don’t lose that number.

Cache directions tell us to take our answers to the Park Office, reminiscent of the awesome Geotrails hosted by our Metro Parks each year. Maybe we will run into a Park Ranger.

And that’s one of the nicest Rangers we’ve ever met. Very smart, too. Knows how to give a great clue.

When our four numbers encounter a genuine padlock, the FUN and REWARDING of the description notches up. Considerably.

Before us opens a treasure trove of imagination, determination, and generosity, a worthy tribute to those who maintain the park we have just enjoyed.

Our footprints walk us back to our car.

Fresh air

a simple shared act of hiding and finding

a mustard seed of generosity spread across continents and languages

wordlessly speaking to the tide of addictive greed

write your own story

Skip to content